Performance of Reduced-Charge Rounds

For the 75mm field gun (Model 1897)

In March of 1917, the French Army introduced a reduced-charge round for its 75mm field guns: the famous Model 1897, the Model 1912 horse artillery piece, and the “limited standard” pieces built by Saint-Chamond and Schneider during the first year or so of the war.

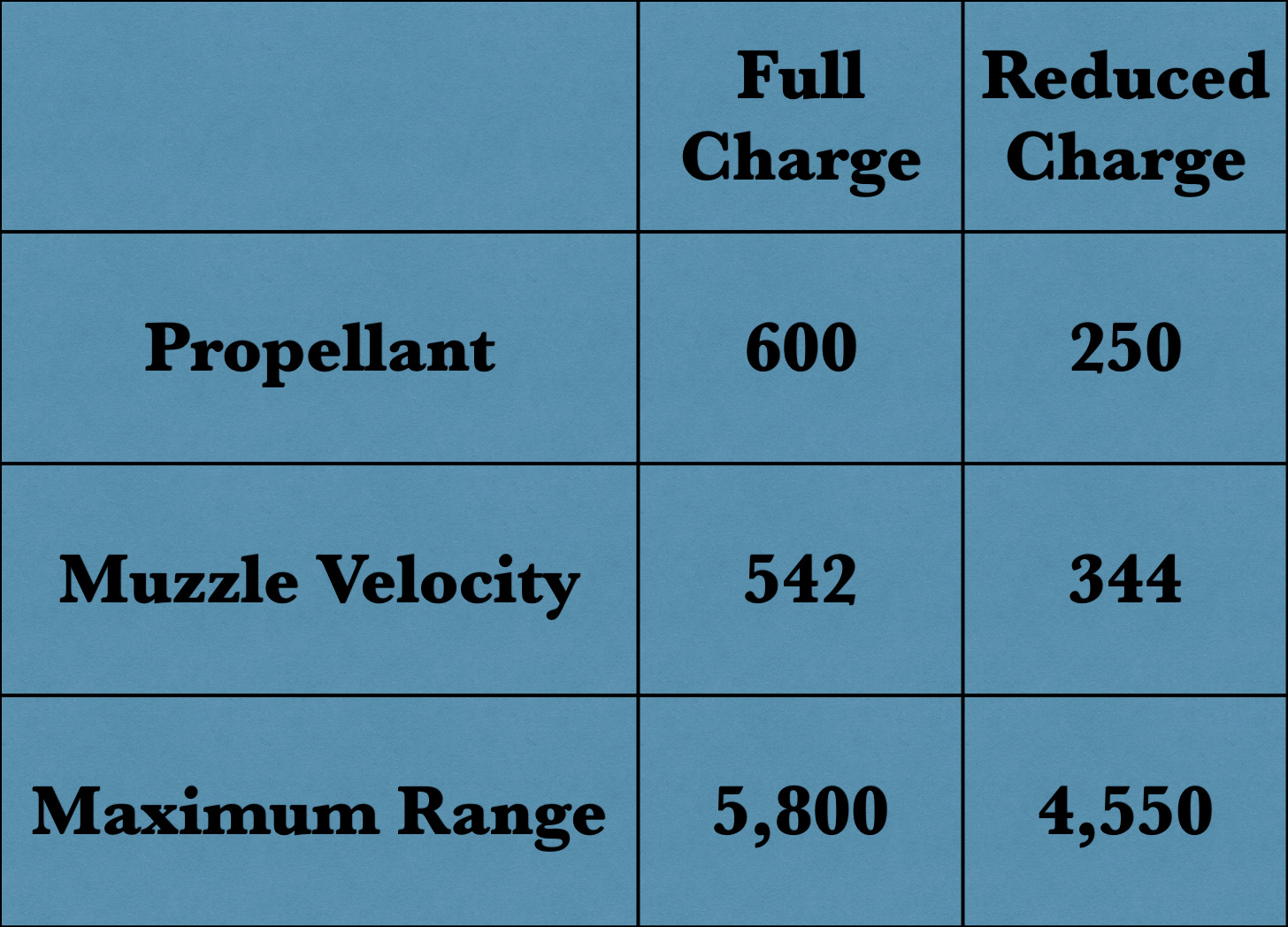

The reduced-charge round bore a close resemblance to the default 75mm cartridge of the day. Like the latter, it consisted of a high-explosive shell (of a type introduced in 1900) and a brass cartridge case. Indeed, apart from markings, the only difference between the two items lays in the amount of propellant packed into the latter container. Where the full-size round carried 600 grams (1.3 pounds) of nitrocellulose, the reduced-charge cartridge made do with 250 grams (0.5 pounds).

When fired from a cannon, the shell of the reduced-charge round flew more slower than its fully-charged counterpart. The decrease in velocity, however, was not nearly as great as the reduction in the amount of propellant. (In round numbers, cutting the amount of propellant burned by 60 percent caused a 40 percent drop in muzzle velocity.)

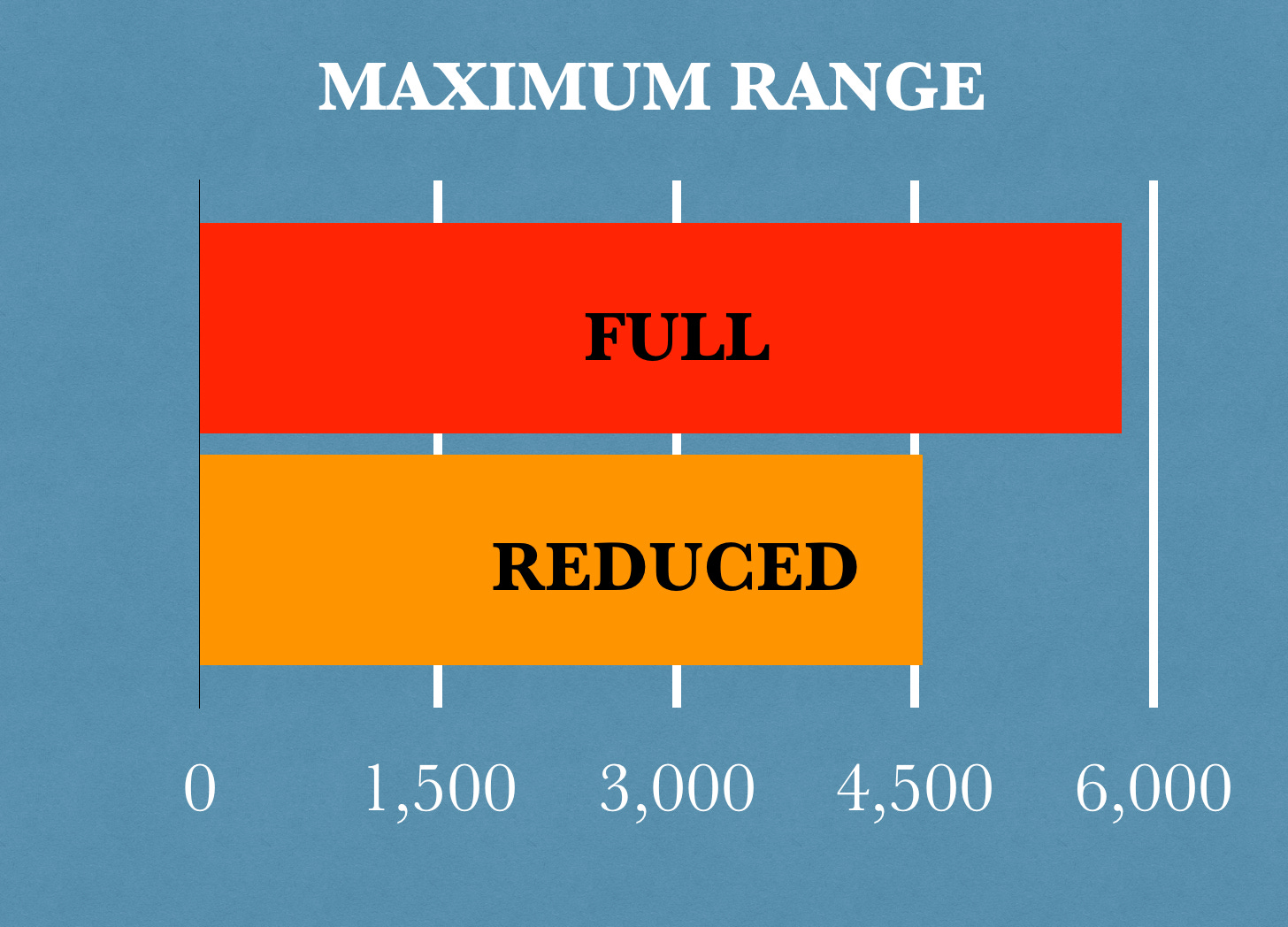

In terms of proportion, the reduction in maximum range resulting from the trimming of the propellant charge was even smaller than the lowering of muzzle velocity. Thus, when fired at 18 degrees (the highest angle permitted by the carriage of the Model 1897 field gun), a shell delivered by the smaller charge would fly a little more than two-thirds as far as a projectile sent forth by its much larger cousin.

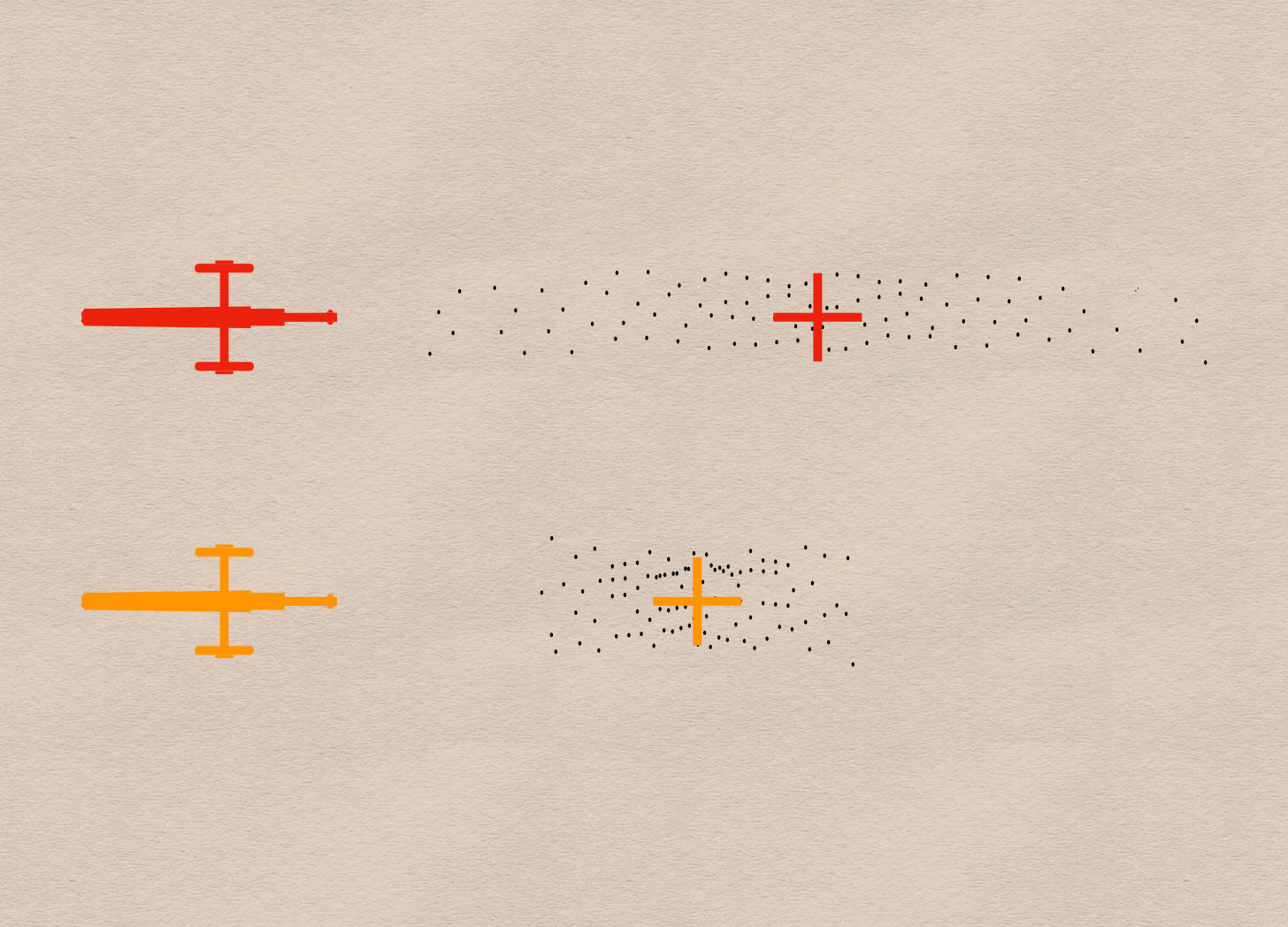

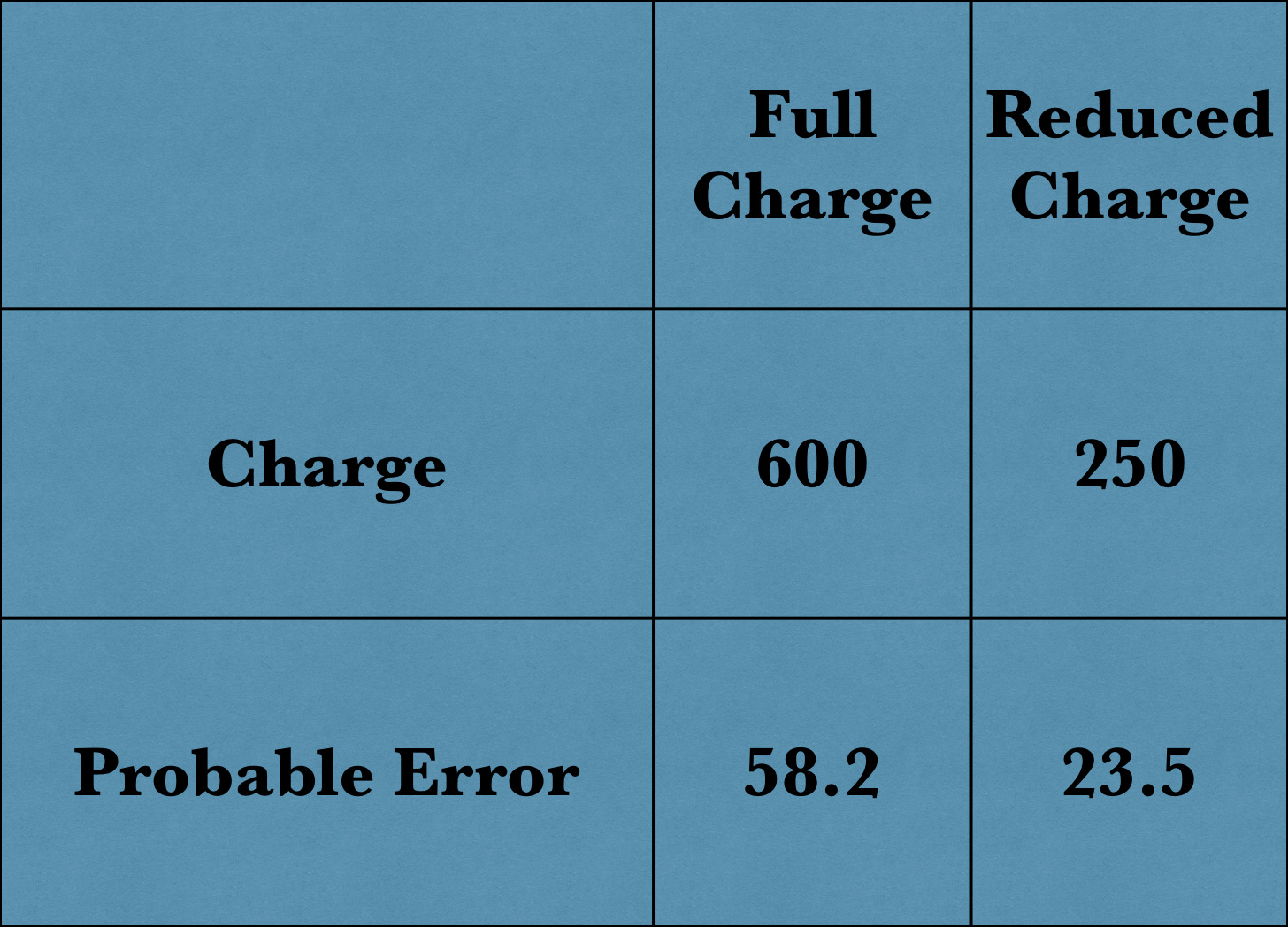

When a hundred 75mm cartridges were fired at a given point on the ground, the fallen shells formed a rectangle, the long axis of which lay along the line of fire. If the rounds employed were of the fully-charged persuasion, the pattern formed was long and thin. If, however, the shells were propelled by reduced charges, the resulting rectangle was both shorter and wider.

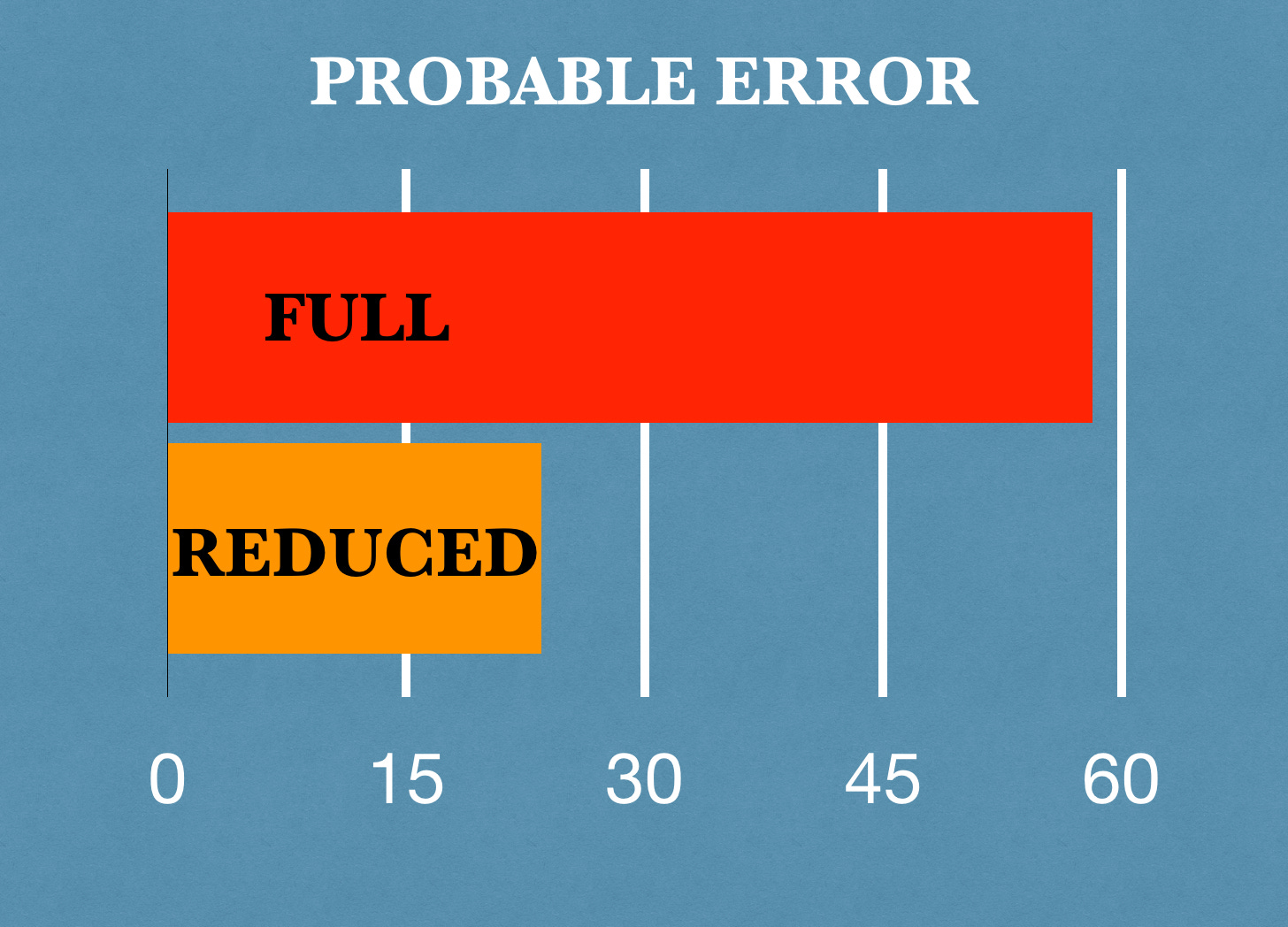

French gunners expressed the density of the aforementioned shapes with a number that they called ‘probable error’ [écart probable]. They came up with this number by measuring, in meters, the length (along the line of fire) of the area in which half of the shells fired had fallen. (This calculation corresponds to the American concept of ‘probable error in range’.)

When fired at maximum range, the ‘probable error’ of cartridge with a large load of powder was more than twice that of one that carried less in the way of nitrocellulose. In other words, when firing at a target (such as a trench) that was perpendicular to the line of fire, reduced-charge rounds were far more accurate than their fully-charged counterparts.

Sources:

The figures used in this post come from Renseignements sur les matériels d'artillerie de tous calibres en service sur les champs de bataille des armées françaises [Information about Artillery Matériel of all Calibers Serving with French Armies on the Battlefield] (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1918), pages 54-56.

The explanation for ‘probable error’ owes much to the Manual for the Battery Commander, Field Artillery, 75mm Gun (Washington: US Army War College, 1917) pages 27-28.

For Further Reading:

To Support, Subscribe, or Share:

Clearly the French Army knew it had a huge problem with accuracy and had to do something fast, especially as the had few field howitzers in production at the time! I think it is worth pointing out this discussion addresses probable error in range, which is measured here in meters.