A Sawed-Off 75

An episode from the spring of 1915

On 13 January 1915, a 75mm field gun of the 17th Field Artillery Regiment blew up. In the days that followed, the men of that unit spent a lot of time sorting ammunition, separating rounds built in improvised factories from the products of state arsenals and other mature munitioneers.

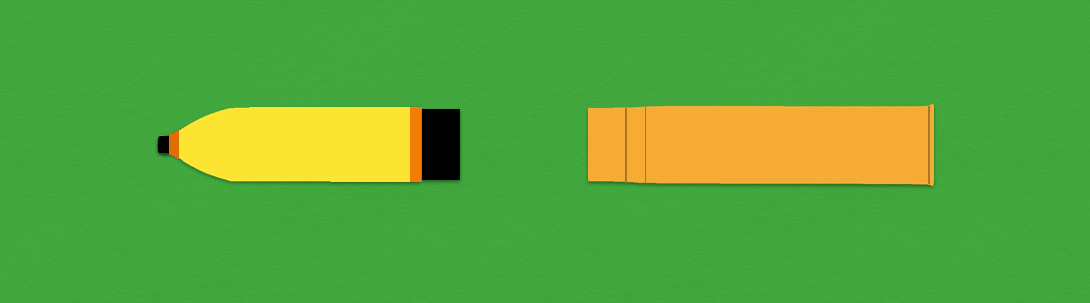

While their comrades performed this chore, someone at a nearby machine shop amputated those parts of the piece that had been damaged by the premature explosion. (The location of this surgery has been lost to history. However, as the accident took place in Argonne Forest, within a day’s wagon ride of Verdun, this operation might well have taken place in one of the workshops of that fortress complex.)

When the cutting was done, the 17th Field Artillery took delivery of the essential elements of a one-of-a-kind device capable of sending 75mm shells into the sky. That is, while the regiment received neither carriage nor cradle, steel shield or wooden wheels, it did get a working breech mechanism, a proper chamber, and a (very short) barrel.1

To make up for the missing parts, someone lashed the truncated barrel assembly to a log, dug a hole for the bottom end of the assemblage, and provided the position with sandbags that, when filled and combined in various ways, permitted the rapid adjustment of elevation.

On 26 May 1915, the new artillery piece fired its maiden mission. Unfortunately, the propellant charge provided with standard rounds provided too much in the way of flash and recoil, and too little predictability. A week later, however, Captain Ribaucour of the 17th Field Artillery and Lieutenant Borda of the 5th Heavy Artillery Regiment solved this problem by removing two-thirds of the propellant held in each brass cartridge case, thereby reducing the charge from 600 grams (21 ounces) to 200 grams (7 ounces).

In the week that followed, Ribaucour applied a similar solution to the problem of firing shells from an ordinary 75mm field gun over the ridges that separated the batteries of the 17th Field Artillery from places occupied (or traversed) by German forces. In order to replace the famously flat trajectories of shells fired by the field gun with curvier ones, he took 250 grams of propellant out of each cartridge case. Moreover, with a view to making this method available to other artillerists of the French Army, Ribaucour used the data he collected in the course of these experiments to construct formal firing tables.2

These experiments with reduced-charge shells seem to have been conducted with the blessing, if not the active encouragement, of the recently-appointed commander of the 17th Field Artillery, Firmin-Émile Gascouin (1866-1940). Lieutenant-Colonel Gascouin, who had previously stood at the helm of the 5th Heavy Artillery Regiment, would later write a book in which he argued that the performance of French artillery during the World War could have been greatly enhanced by the use of reduced-charge ammunition and carriages that permitted guns to be fired in the manner of howitzers.

Two years later, in the summer of 1917, batteries armed with 75mm field guns began to receive shipments of cartridges that had been filled, in the course of manufacture, with 250 grams of propellant. Unfortunately, while Gascouin’s book contains many complaints of the tardiness of this measure, it makes no mention of Captain Ribaucour, Lieutenant Borda, or the experiments conducted in May of 1915. What is worse, the war diaries that might have shed some light on the two-year gap between improvisation and official adoption are missing from the collection of such documents that the Defense Historical Service [Service Historique de la Défense] has placed on line.

Sources:

War Diary of the 2nd Battery of the 17th Field Artillery Regiment [17e Régiment d’Artillerie de Campagne, 2e Batterie, 5 août 1914-19 juin 1915 Journal des Marches et des Opérations (26 N 934/24)] pages 49-51

Firmin-Émile Gascouin The Evolution of Artillery during the War [L’Évolution d’Artillerie Pendant la Guerre] (Paris: Flammarion, 1920)

For Further Reading:

To Support, Share, or Subscribe:

A photograph of the home-made howitzer can be found here, on the forum of the splendid website Pages 14-18. The picture was taken on 8 May 1915 by a medical officer serving with the 91st Infantry Regiment, a unit that was then part of the same army corps (2nd Army Corps) as the 17th Field Artillery Regiment.

Captain Ribaucour may have been Henri Ribaucour (1881-1954), the son of military engineer Charles Ribaucour (1846-1895) and the nephew of mathematician Albert Ribaucour (1845-1893). If this is so, he graduated from the École Polytechnique in 1903 and attended a the Superior Technical Artillery Course at Bourges in 1911.

What a great story. 👍🏻

Like a sawed off shotgun it has it’s uses.