You can’t use a howitzer - a true howitzer, that is, a short-barreled artillery piece of the type employed at the start of the First World War - like a gun. For one thing, the chamber is too small to accommodate the charge needed to propel a shell at gun-like speeds over a gun-like trajectory in order to reach targets at a gun-like distance. Even if you could find some way to fit more powder into the piece, the shell would depart the muzzle well before the charge finished burning.

You can, however, use a gun like a howitzer. That is, you can use a smaller charge to propel a shell slowly over a curved path in order to hit a target that is not too far away. It would, of course, be helpful if the gun could elevate its barrel in the manner of a howitzer. That ability, however, is far from indispensable. After all, you can always dig a hole for the trail, build a ramp, or, if you are really ambitious, mount the gun on an upturned wagon wheel.

Using a gun like a howitzer is, of course, fails to make use of a good two-thirds of its barrel, and thus two-thirds of the weight of the weapon as a whole. When one is building, buying, or moving a gun, it’s hard to tolerate this sort of inefficiency. However, when the gun has already been built, paid for, and moved into its firing position, it is much easier to bear the waste of so much metal, money, and horsepower. Likewise, if the sub-optimal use of a light field gun allows it to be used for a wider range of purposes, then an army might be able to dispense with howitzers of the same weight class.

In the 1880s, German gunners experimented with the use of smaller-than-usual propellant charges. Such “reduced charges” [verkleinerten Ladungen], the artillerists hoped, would allow shells fired by their 9 cm field guns (Model 1893) to reach targets protected by trenches, low ground, and intervening hills. However, as the higher angles of fall achieved by this method failed to meet expectations, the German ordnance authorities began to explore the possibility of a howitzer that, having a caliber in the range of 100mm to 120mm, would be light enough to keep up with field guns on the march.1

French gunners of the same era followed a similar path. However, where their German counterparts had used their verkleinerten Ladungen to propel projectiles filled with explosives, they used charges réduites to deliver shrapnel. However, once they discovered that smaller charges deprived the lead bullets carried by such shells of much of their effect, they decided to pursue the possibility of a 120mm field howitzer.2

Soon after the start of the twentieth century, two developments led to a revival of interest in reduced-charge ammunition for field guns. The debut of the 75mm field gun (Model 1897) increased the number of places where, all other things being equal, foemen might enjoy the advantages of defilade. At the same time, the introduction of shells filled with melinite reduced the degree to which the destructive power of a projectile depended upon its velocity.

In 1905, Louis Baquet proposed changes to the 75mm field gun cartridge that would allow the gun crew to remove, with ease, some of the propellant prior to firing.3 This, he argued, would allow French field batteries to drop high explosive shells on enemies in defilade, thereby dispensing with all artillery pieces save the 75mm field gun and the 155mm howitzer.4 (Marvelous to say, the piece that would have been made redundant by this measure, the 120mm light field howitzer adopted in 1890, had been invented by none other than Baquet himself.)

Alas, Baquet’s proposal fell on deaf ears. Thus, French gunners had to wait twelve years before they received reduced-charge ammunition for their 75mm field guns.

The reduced-charge ammunition of 1917 lacked the adjustability imagined by Baquet. That is, Baquet had proposed, avant la lettre, the provision of what would later be called “semi-fixed ammunition.” The 75mm rounds issued to French gunners during the last nineteen months of the First World War, however, were of the “fixed” variety. Thus, unless provided with special tools and special skills, the gunners who handled them could not change the amount of propellant they contained.

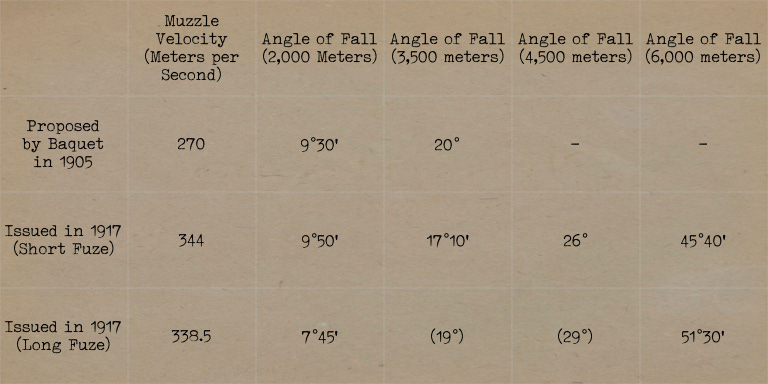

The reduced charges of 1917 were larger than those proposed by Baquet. Thus, the shells that they propelled flew much faster, fell more gradually, and enjoyed a considerable advantage when it came to range. While shells fired with Baquet’s reduced charge would have flown no further than 3,500 meters, those set in motion by the reduced charges of 1917 could reach 4,500 meters. (If the trail had been placed in a hole or the piece mounted on a ramp, the latter could reach 6,000 meters.)5

For Further Reading:

To Share, Subscribe, or Support:

Heinrich Rohne “Die Entwicklung der Moderne Feldartillerie” Vierteljahreshefte für Truppenführung und Heereskunde (1904) page 492 (An abridged translation of this article, under the title of “Les Progrès de l’Artillerie de Campagne,” can be found in the issue for April 1905 of the Revue d’Artillerie.)

Jules Challéat L’Artillerie de Terre en France pendant un Siècle: Histoire Technique (1816-1910) (Paris: Charles-Lavauzelle, 1935) Tome II page 71

Louis Baquet Souvenirs d’un Directeur d’Artillerie (Paris: Charles-Lavauzelle, 1921) page 31

Challéat L’Artillerie de Terre Tome II page 480

École Militaire d’Artillerie École de Commandant de Batterie: 1ère Partie, Canon de 75 (Paris: Chapelot, 1917) page 48

Note: On the chart, the figures within parentheses were derived by (very rough) interpolation by a person who last did serious mathematics during the presidency of James Earl Carter.

I wonder what the effect on range and trajectory would have been if the French had used reduced charges and the Plaquettes Malandrin discussed a few days ago? It would still be not as good as redesigning the M1897 so it was a true gun-howitzer, or developing an actual light field gun-howitzer or just howitzer, but better than nothing.