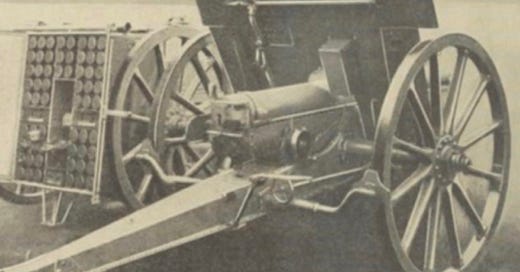

In the ten years or so leading up to 1914, the French steelmaking firm of Schneider and Company designed, and offered for sale, a variety of 75mm light field guns. These shared many features with the weapon that Americans would later call the ‘French 75’, the canon de 75 (Modèle 1897) of the government arsenal system, things such as fixed ammunition, mechanical fuze setters, and, in all cases but one, hydro-pneumatic recoil-absorbing systems.

At the same time, the Schneider seventy-fives sported barrels that were shorter than those of the state-built originator of their class. This resulted in lower weight, which made them easier to move on bad roads. At the same time, it diminished the amount of propellant that could be burned before the shell passed through the muzzle, thereby reducing both muzzle velocity and range.1

Like other private arms makers of the early twentieth century, Schneider operated in much the same way as a maker of bespoke suits, with a series of stock designs that could be adapted to meet the needs and desires of the customer. In a few cases, Schneider would modify these models in order to accommodate ammunition of pre-existing types. Thus, when making guns and howitzers for the Russian Army, it converted stock 75mm and 120mm pieces into weapons that could fire the 76.2mm and 122mm shells already in the Russian inventory.

In the absence of such arrangements, guns and howitzers built by Schneider fired ammunition of proprietary types, stock items that bring to mind the replacement blades for present-day shaving razors. That is, while resembling the consumables made by their competitors, the default rounds provided by Schneider differed from their counterparts in ways that, while seemingly minor, prevented interchangeability.

Because of this, when it came time to refill their caissons, states that had purchased guns and howitzers of types that used Schneider-specific ammunition could either order replacement rounds from Schneider or purchase a license to build suitable shells, fuzes, propellants, and cartridge cases in their own arsenals. (As recent events in Ukraine have reminded us, developing the ability to do the latter required both specialized machinery and people with the peculiar skills needed to run it.)

The outbreak of the First World War found Serbia, which had armed nearly all of its field batteries with Schneider pieces, using both methods to replace the 75mm field gun rounds it had fired in the course of the Balkan Wars. Unfortunately, hostilities began before this combination of production and purchase had managed to make much of a dent in the deficit.

In the crisis that followed, Serbia obtained temporary relief by importing Schneider-made shells from Greece. It also asked the French government to supplement the shipments sent out by Schneider.

In meeting the latter request, the French authorities mistakenly despatched a consignment of rounds of a type built for use with the Model 1897 field gun. Thanks to brass cartridge cases that were 2.5 millimeters longer than the cartridge cases of standard Schneider ammunition, these prevented the breach mechanisms on Schneider field guns from closing.

To solve this problem, Serbian ordnance officers shipped the offending rounds to the arsenal at Kragujevac, where machinists removed trimmed the tops of the cartridge cases. (Needless to say, the shells were detached, and the propellant charges removed, before the craftsmen began to cut into the metal.)

Sources:

In ‘The Serbian Army and its Struggle with the Ammunition Crisis of 1914’ Istorija 20. Veka [History of the 20th Century] (1/2024), Danilo Šarenac uses the delivery of the wrong kind of ammunition to Serbia in 1914 as a springboard for a delightfully detailed discussion of Serbian artillery pieces and the rounds they fired.

Figures for matériel used by the French Army comes from Renseignements sur les matériels d'artillerie de tous calibres en service sur les champs de bataille des armées françaises [Information about Artillery Matériel of all Calibers Serving with French Armies on the Battlefield] (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1918)

Figures for matériel designed by Schneider and Company comes from Schneider et Cie Les Établissements Schneider: Matériels d'artillerie et bateaux de guerre (Paris: Imprimerie de Lahure, 1914)

For Further Reading:

To Support, Share, or Subscribe:

The figures given in the chart presume a shell that weighs 6.5 kilograms. In the case of Schneider guns, this is the standard Schneider shell. In the case of the Model 1897 gun, this is the semi-steel explosive shell adopted in 1918 [obus explosif fonte aciérée modèle 1918].