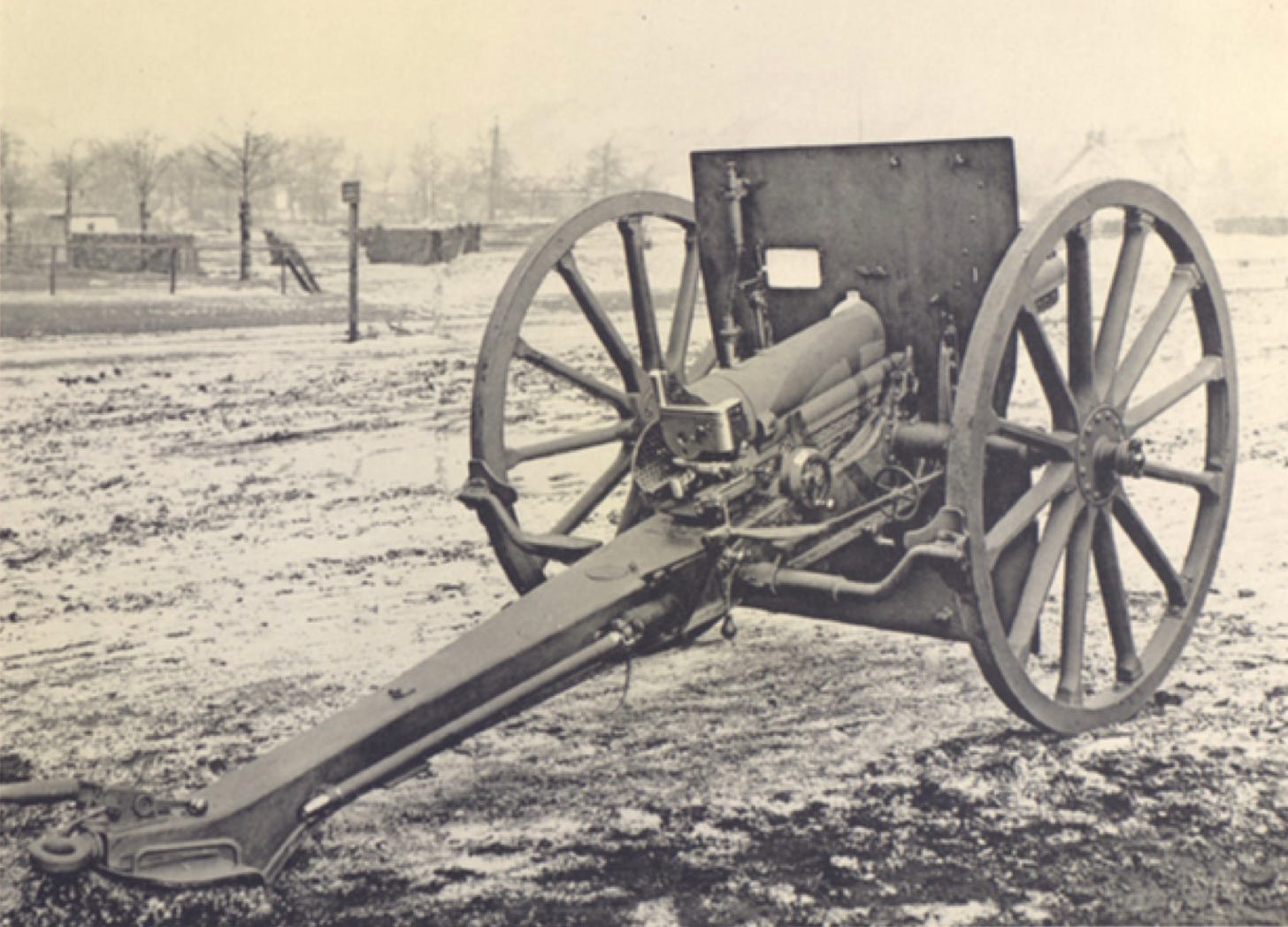

During the four decades that followed the end of the Franco-Prussian War (1871), government arsenals produced all of the artillery pieces issued to operational units of the French Army. In 1912, however, the French government approved a plan to arm horse artillery batteries with a weapon purchased from the private firm of Schneider and Company. This 75mm field gun (Model 1912) weighed less than the 75mm field gun (Model 1897) issued to the field batteries of infantry divisions and army corps. Nonetheless, it used the same ammunition as its older, heavier, state-built counterpart.

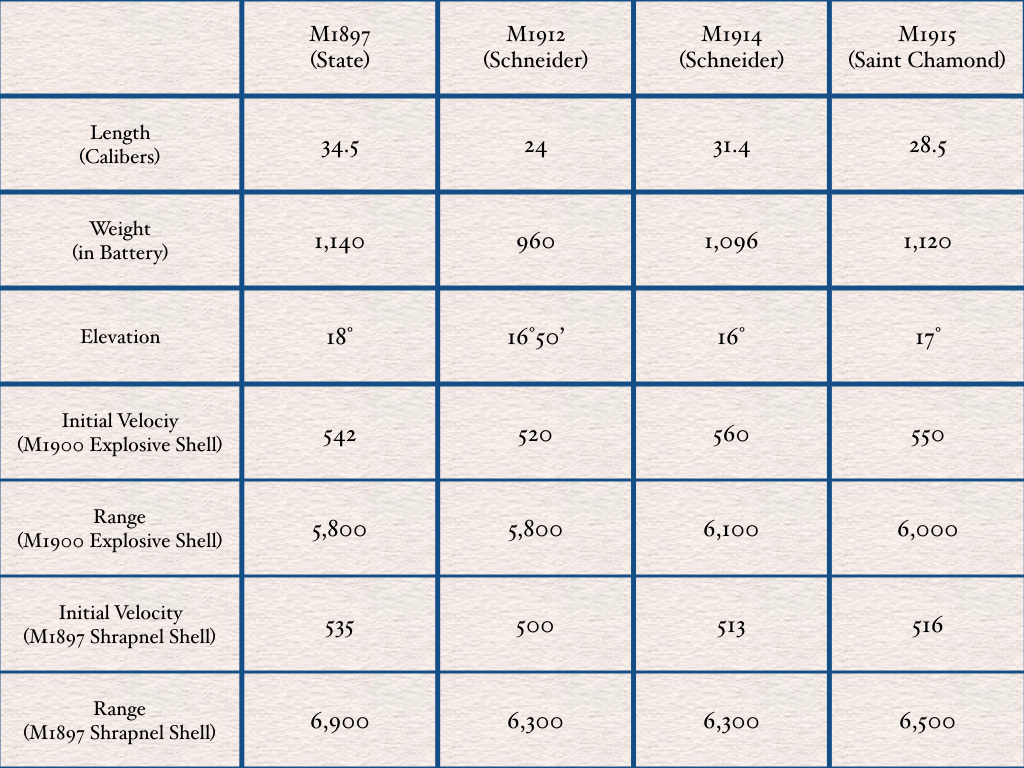

The difference in weight between the two weapons owed much to the shorter barrel of the privately-made piece. The shorter barrel, in turn, reduced, if only to a small degree, the effectiveness of the shrapnel shell adopted in 1897 for use with the Model 1897 field gun. (This was partially a matter of range and partially a matter of the velocity imparted to the shrapnel balls.) However, as the destructive power of explosive-filled shells depended entirely (or nearly so) upon the detonation of their contents, the reduction on barrel length did little, if anything, to diminish the effectiveness of such projectiles.

During the two years leading up to the outbreak of the First World War, the French Army equipped thirty batteries of horse artillery with Model 1912 field guns. Assigned to cavalry divisions, these weapons spent the first few weeks of the First World War in motion. However, with the onset of position warfare, they often found themselves performing the same sort of tasks as Model 1897 field guns.

In September of 1914, the French War Ministry placed an order with Schneider for forty-eight additional weapons of this type. In the same month, the war ministry purchased thirty-two 75mm field guns based on a type (the PD7) that Schneider was then building for the Greek Army. While similar in many respects to the Model 1912 pieces, this somewhat heavier gun (which the French authorities would call the “Model 1914” field gun) sported a somewhat longer barrel.

In October of 1914, the WarMinistry asked another arms maker, Saint Chamond, to make one hundred and sixty copies of a field piece that it had previously produced for the Mexican Army. Like other the other “off the shelf” field pieces, this weapon, which had been designed to fire less powerful ammunition, was to be modified in ways that allowed it to use the same ammunition as the Model 1897 field gun. (Employees of Saint Chamond described the piece as the “Model 1915.” French soldiers, however, called it the “Saint Chamond.”)

The program to acquire these “off-the-shelf” weapons stemmed from a desire to provide the many new formations then being formed with full-strength field artillery establishments. Ideally, the new batteries formed for these infantry divisions and army corps would have been armed with the standard (Model 1897) field guns of the French Army. Unfortunately, such weapons were not to be had. (Most of the spare Model 1897 field guns that had been available at the start of the war had been used to replace ordnance lost during the first six weeks of the war. To further complicate matters, the state arsenals that had manufactured the pre-war stock of Model 1897 field guns had their hands full with the production of projectiles.)

Within weeks of the placement of these orders, the project to acquire new non-standard 75mm field guns ran afoul of other priorities. In the case of Schneider, the project to build 75mm field guns took tools and talent away from the manufacture of the only modern mobile heavy piece in service with the French Army, the 105mm heavy field gun (Model 1913). In the case of Saint Chamond, the company needed the assistance of the state arsenal at Saint Étienne to make key elements of the carriages for their 75mm field pieces. Both companies, moreover, were also failing to meet their obligations in the realm of ammunition. Thus, for the sake of more pressing priorities, the War Ministry put a stop to plans to acquire additional 75mm guns of commercial types and adjusted the schedule for the delivery of those that had already been ordered.

In 1915, while the projects of make commercial 75mm guns languished on the proverbial “back burner,” the state arsenals resumed the production of new 75mm field guns of the standard type. Thus, by the spring of 1916, when the French authorities began to take delivery of Model 1912, Model 1914, and Saint Chamond field guns, the worst of the shortage of weapons of the class had passed. Thus, while precise figures have yet to present themselves, it seems that few of the 75mm field guns made by Schneider and Saint Chamond spent more than a few months with French forces in Europe before being replaced by 75mm field guns of the model adopted in 1897.

Sources:

The figures for the Model 1897, Model 1912, and Saint Chamond field guns come from Ministre de l’Armament et Fabrications de Guerre Renseignements sur les Matériels de Tous Calibres en Service sur les Champs de Bataille des Armées Françaises (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1918) pages 53-64

The figures for the Model 1914 field guns come from Les Établissements Schneider, Matériel d’Artillerie et Bateaux de Guerre (Paris: Imprimerie Générale Lahure, 1914) page 82 and the reliably splendid website Bulgarian Artillery.

Information about the orders placed by the War Ministry for commercial 75mm field guns come from Louis Baquet Souvenirs d’un Directeur d’Artillerie (Paris: Charles-Lavauzelle, 1921) pages 105-106

For Further Reading:

To Share, Subscribe, or Support:

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volleyed and thundered;

Stormed at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of hell

Rode the six hundred.

Damn. I came here for the seventy french fries...