Complementing the Curious Carriages

A path not taken (Part IV)

This is the fourth post in the multi-part series. To read the first three parts of this article, please follow the following links:

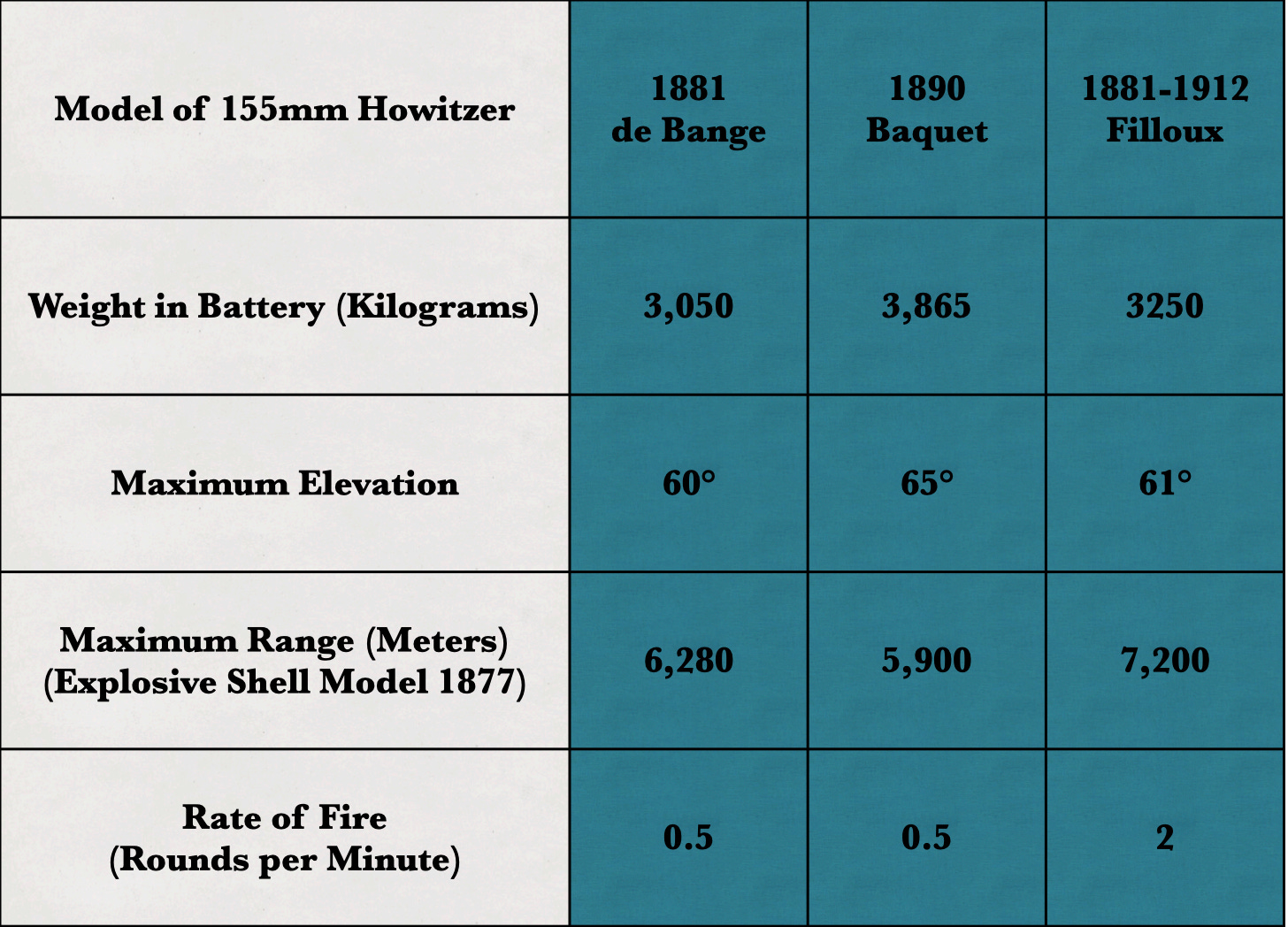

At the point of departure of this counter-factual speculation, the French Army possessed two types of field howitzers. The smaller of the two, the 120mm “short gun” [canon court] fired the same projectiles as the 120mm gun of 1878. The larger, the 155mm short gun, used the same shells as the two 155mm pieces of the de Bange family.

The handiwork of Louis Baquet, both of the field howitzers had been designed, tested, and adopted at the same time. Thus, both had been given the same model year (1890), bore the same informal designation (“Baquet”), and used the same on-carriage recoil-absorbing mechanism.

Like the device designed by Léon Mourcet, the recoil-absorbing mechanism of the Baquet pieces consisted of a “small mounting” [petit affût] and a “large mounting” [grand affût]. Nonetheless, guns mounted on Mourcet’s carriage could fire four shells in the time a Baquet howitzer needed to fire one.

The chief reason for this difference was the way that each small mounting (and thus the barrel attached to it) moved forward after recoiling. Where the Mourcet mechanism returned the small mounting to the exact place it had occupied at the moment the lanyard was pulled, the device built by Baquet proved far less precise. Thus, before he could fire a second shot, the gunner had to spend time adjusting the point-of-aim of the piece.

Unfortunately, the attempt by Mourcet to mate his carriage to the barrel of the larger of the two Baquet howitzers failed to solve this problem. Thus, it is likely that, in the decade or so (1895 to 1905) that the French Army spent mounting its inventory of 90mm and 95mm field pieces on Mourcet carriages, it would attempt to obtain a mobile heavy piece (or two) with a better rate of fire.

One possible solution to this problem would involve the use of Mourcet-mounted 120mm guns as all-purpose mobile heavy pieces. These “gun-howitzers” could use large charges to propel projectiles over flatter trajectories and the combination of small charges with high angles of fire to toss them in the manner of howitzer shells. Because of this, it is easy to imagine that the formation, on the eve of the Great War, of heavy field artillery regiments that, while similar to the régiments d’artillerie lourde of our time line, were armed exclusively with 120mm heavy guns mounted on Mourcet carriages.

The 120mm gun on the Mourcet carriage would be able to outrange any of the artillery pieces customarily assigned to German army corps - the 77mm field guns, the 105mm light field howitzers, and the 150mm heavy field howitzers. At the same time, the shell that it fired would be much heavier than that of the German 105mm howitzer and slightly heavier than the shell fired by the 105mm mobile heavy gun adopted in 1904.

At the same time, the 120mm dual-purpose piece would not be able to perform the definitive task of heavy field howitzers. That is, while both German 150mm howitzers and the older 155mm howitzers in the French inventory possessed the combination of accuracy and shell power to destroy trenches, the 120mm piece could do little more than dissuade German soldiers from leaving the relatively safety of such shelters.

Thus, while 120mm guns mounted on Mourcet carriages might replace the 120mm Baquet howitzers, it is likely that the French Army would both retain the 150mm Baquet howitzer and begin a program to replace it with a weapon of the same caliber that enjoyed a higher rate of fire. The leading candidate for such a replacement would have been 155mm howitzer mounted on the mounting designed by Louis Filloux that, in our time line, was adopted in 1912.

Captain Filloux designed his mounting in 1903. However, thanks to the low priority accorded to the project by both the arsenal charged with building prototypes and the authorities charged with the testing of new ordnance, it was not adopted in 1912.1 Sturdier than both the non-recoiling de Bange mounting and the recoil-absorbing Baquet carriage, the Filloux mounting allowed the use of the larger charges needed to attain longer ranges. Better yet, it permitted a rate of fire that was four times as fast as that of its competitors.

The one drawback to the Filloux mounting was the need to employ a transportable platform that weighed more than two metric tons. Thus, the task of moving a 155mm howitzer Filloux howitzers into its firing position took much longer than the process of preparing the Baquet howitzer to fire. For this reason, while the French authorities designated the Baquet howitzer as a field piece, they classified the Filloux howitzer as a “siege and fortress” [de siège et de place] weapon.2

For Further Reading:

To Subscribe, Share, or Support:

For a précis of the development of the Filloux carriage, see Jules Challéat L'artillerie de terre en France pendant un siècle : histoire technique (1816-1919), Tome II [Land Artillery in France over the course of a Century: Technical History (1816-1919), Volume II] (Paris: Charles-Lavauzelle, 1935) pages 400-401.

The characteristics of the various types of 155mm howitzers come from Renseignements sur les matériels d'artillerie de tous calibres en service sur les champs de bataille des armées françaises [Information about Artillery Matériel of all Calibers Serving with French Armies on the Battlefield] (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1918) pages 142-150.

Hope someone in R&D reads about Mourcet.