The Curious Carriage of Captain Mourcet

A path not taken (Part I)

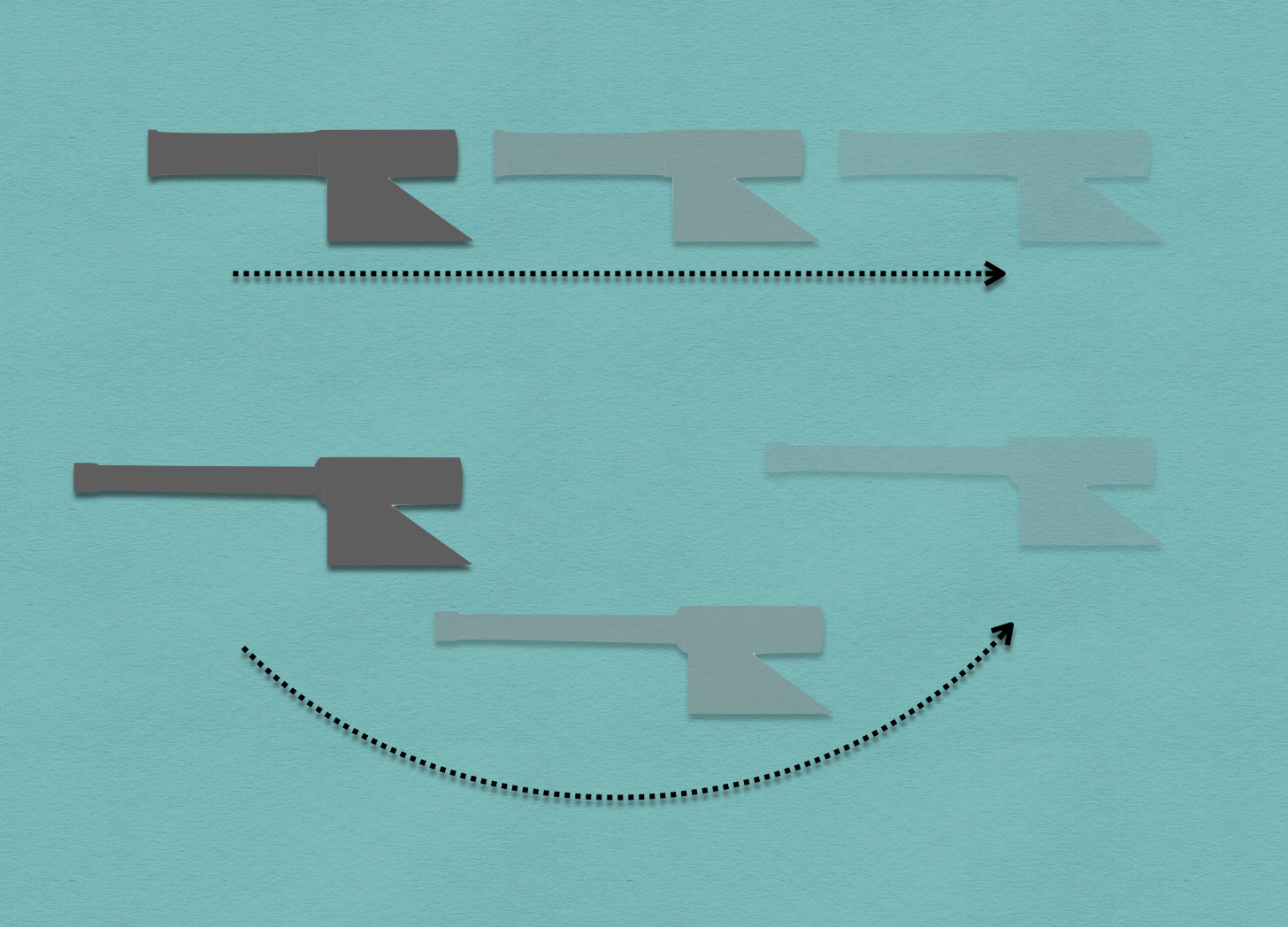

In the early 1890s, Léon Arthur Mourcet of the French Army designed a carriage for artillery pieces that absorbed the rearward forces created by the act of firing. Like many other non-recoiling carriages of the period, this device consisted of two major elements: a small mounting [petit affût] that recoiled with the barrel of the gun and a big mounting [grand affût] that remained in place. However, where the small mountings of other carriages slid along straight rails, the small mounting of Captain Mourcet followed a circular path. In other words, while small mountings of other types moved, both backwards and forwards, along a line that ran parallel to the ground, the petit affût Mourcet rocked.

The rocking of the small mounting on Mourcet’s carriage generated downward forces that added greatly to its stability. Thus, where straight-line carriages could only handle the smaller rearward forces produced by howitzers, Mourcet’s curved-path carriage could manage the more powerful recoil of guns.1

Mourcet designed the first carriage of this sort to carry the standard weapon of French field batteries of 1890s, the 90mm field gun of the de Bange family that had been adopted in 1877. Unfortunately, in building his first prototype, he made a mistake with the placement of the spade. Thus, when he demonstrated the new carriage in front of the board charged with evaluating such devices [le Comité technique de l’artillerie], it performed poorly. Worse, minor problems with an improved version prototype led to further delays in the program.

It was not until after the perfection of the design of the 75mm field gun (Model 1897) that Mourcet was able to convince the relevant of authorities of the viability of his project. However, having seen the rapidity with which the revolutionary new weapon could be loaded and fired, the latter found fault with the relatively slow speed with which the gun resumed its original position after firing.

Notwithstanding this concern, the board saw considerable potential in the curvilinear carriage. It thus commissioned Mourcet to create a version of his carriage for the de Bange 155mm howitzer (Model 1881). (This, the members hoped, would provide the heavy field batteries of the French Army with a replacement for the straight-sliding carriage for that piece that had been adopted in 1890.)

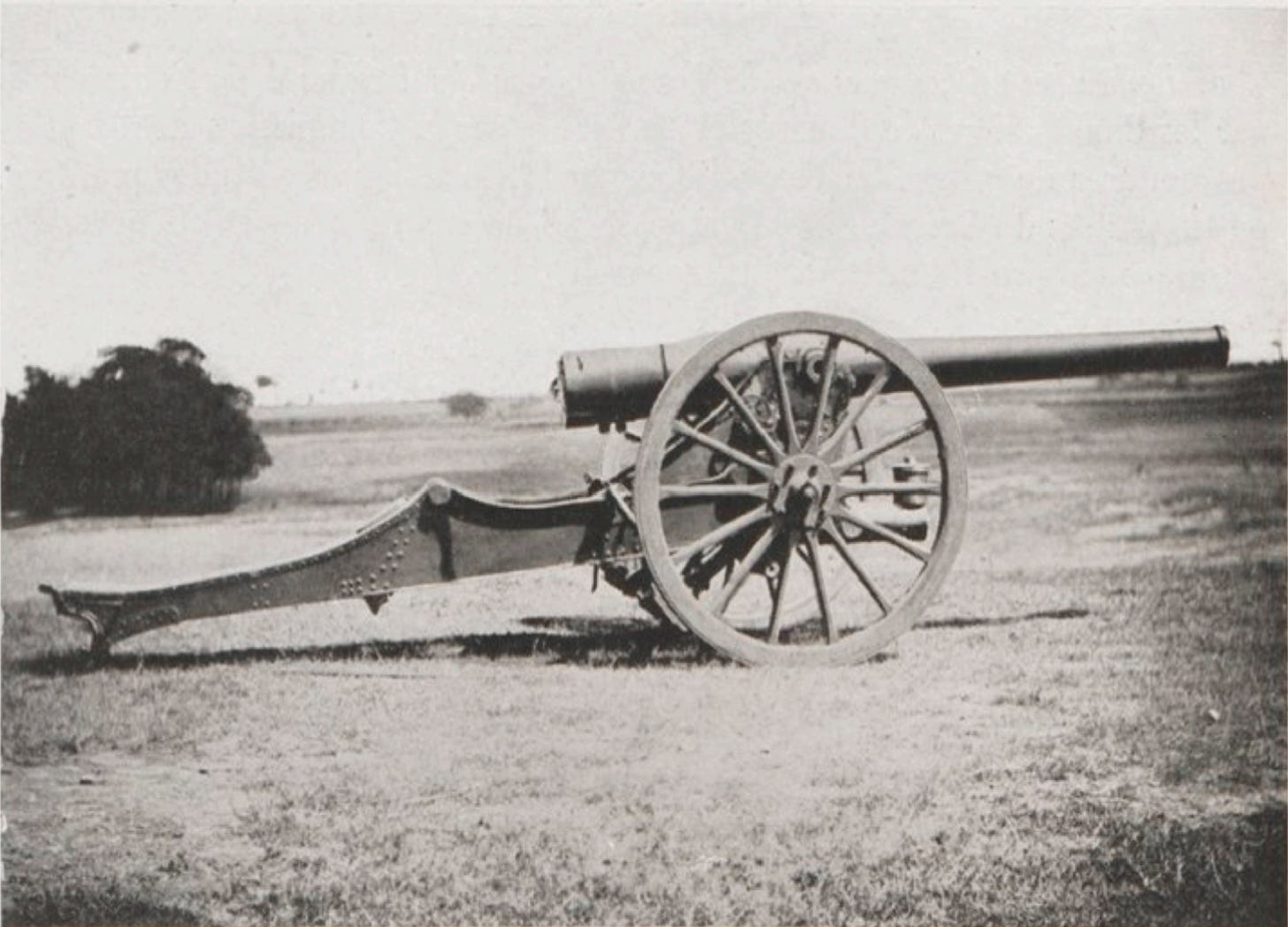

Mourcet seems to have suspected that the attempt to adapt his carriage to the milder recoil of a howitzer would probably prove to be a fool’s errand. He therefore devoted much of the time (and, one presumes, the other resources) given to him to design a carriage for 155mm howitzers to a project to develop a carriage for a weapon that might well be described as a scaled-up version of the 90mm field gun: the 120mm heavy gun (Model 1878).2

To be continued ….

For further reading:

To share, subscribe, or support:

The 120mm howitzer mounted on two-part recoil-absorbing carriage (Model 1890 Baquet) used 550 grams of propellant to project a 19.2 kilogram shell with a muzzle velocity of 284 meters per second. The 120mm gun of the type (Model 1878 de Bange) that Mourcet fitted to his carriage used 1,600 grams of the same propellant to fire the same type of shell at a muzzle velocity of 478 meters per second. Ministère d’Armament et des Fabrications de Guerre Renseignements sur les matériels d'artillerie de tous calibres en service sur les champs de bataille des armées françaises [Information about Artillery Matériel of all Calibers Serving with French Armies on the Battlefield] (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1918) pages 106 and 110

Jules Challéat L'artillerie de terre en France pendant un siècle : histoire technique (1816-1919), Volume II [Land Artillery in France over the course of a Century: Technical History (1816-1919), Volume II] (Paris: Charles-Lavauzelle, 1935) pages 294-297

Tease