This is the second part of a multi-part post. The following link will take you to Part I of the article:

True to its name, the canon de 120 de siège et de place [120mm siege and fortress gun] had been adopted, in 1878, as a means of “dismounting” hostile guns peeking over stone battlements and combatting enemy siege pieces that were attempting to do the same to the guns of French fortifications. Indeed, French gunners had placed such a high value on this mission that 37 percent of the artillery pieces assigned to standard siege train consisted of this weapon.1 By 1902, however, the replacement of open gun positions by armored turrets had reduced the need for such weapons, to the point where the percentage of 120mm heavy guns in an ideal équipage de siège had fallen below 20 percent.2

In keeping with this change in expectation, none of the officials who presided over the tests of the carriage that Léon Mourcet developed for the 120mm heavy gun saw any reason to champion the invention. Thus, while the combination of the old gun and the new carriage “had always proved satisfactory,” the prototype ended up in a warehouse at the arsenal at Bourges, a facility that might well be described as the military analog of the Island of Unwanted Toys.3 As for Mourcet, he obtained a time-in-grade promotion to the rank of major [chef d’escadron], an assignment as the second-in-command of the arsenal at Tarbes, and, two years before his retirement, membership, with the rank of chevalier, in the Légion d’Honneur.4

In 1908, Mourcet received patents for two devices, one of which was a spring-based recuperator for an on-carriage recoil-absorbing system.5 Two years later, after thirty-eight and a half years of uniformed service, which culminated in a tour of duty as commandant of the artillery of Paris, he retired. Soon thereafter, while still living in Paris, he married Jeanne Marie Leloup, the widow of a certain Monsieur Vaillant.6

At the start of the Great War, Mourcet returned to the arsenal at Tarbes, where he supervised the production of artillery ammunition. Soon thereafter, the president of the Testing Committee [Comité d’experiences] at Bourges wrote to the General Staff in Paris, recommending that the half-forgotten carriage be put into production, thereby providing a quick solution to the shortage of modern heavy artillery serving with French forces in the field, and, in particular, to the challenge posed by German heavy field howitzers.

Alas, the proposal found no favor among the extraordinarily busy officers of the General Staff. Thus, many French gunners spent two, three, and even four years rolling antiquated artillery pieces back into battery, while waiting for up-to-date heavy guns and howitzers to appear at the front.

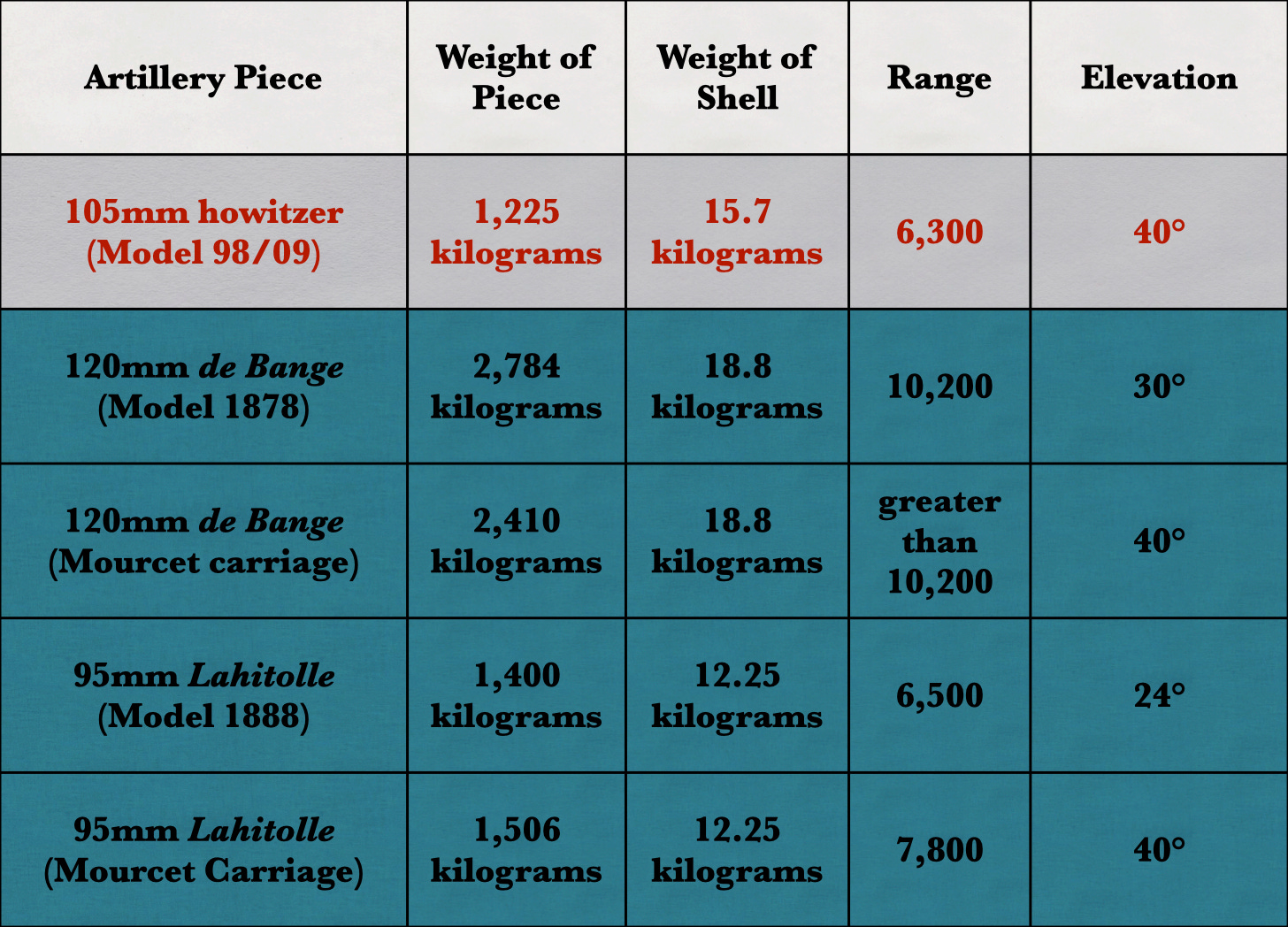

In 1920, Firmin Émile Gascouin, an artillery officer who had, among other things, commanded the field artillery of three infantry divisions, wrote a book in which he argued that the mating of older artillery pieces to the Mourcet carriage would have solved many of the defects suffered by the artillery of the French Army during the war. In particular, General Gascouin argued that mounting 120mm de Bange heavy guns on Mourcet carriages would provided French gunners with a weapon comparable to the 105mm light field howitzers of the German armies. Indeed, he pointed out, the Mourcet-mounted 120mm gun would not only have been able to reach defiladed targets in the manner of the German howitzer, but would both outrange its German counterpart and deliver a substantially larger shell.7

Gascouin also postposed the possibility of completing an artillery park composed of a thousand or more 120mm pieces on Mourcet carriages with a similar number of similarly mounted 95mm heavy field guns. 8 Adopted in 1875, and improved in 1888, these Lahitolle guns fired shells that were lighter than those tossed by the German 105mm howitzer. At the same time, they would, if mated to Mourcet carriages, have enjoyed a considerable advantage in the realm of range.9

To be continued …

For Further Reading:

Emploi de l'artillerie dans la guerre de siège : cours d'artillerie [Employment of Artillery in Siege Warfare: Course in Artillery] (Paris: École Supérieure de Guerre, 1902) page 119

Jules Challéat L'artillerie de terre en France pendant un siècle : histoire technique (1816-1919), Tome II [Land Artillery in France over the course of a Century: Technical History (1816-1919), Volume II] (Paris: Charles-Lavauzelle, 1935) page 12

The characterization of the performance of the Mourcet carriage as having “always proved satisfactory” [“toujours donné satisfaction”] comes from Capitaine Leroy Cours d'artillerie. Historique de l'artillerie de l'origine à 1914 (Fontainebleu: École Militaire d’Artillerie, 1922) page 62.

File of Léon Arthur Mourcet at Léonore, the database of the Légion d’Honneur and Challéat L’artillerie de terre en France, Tome II page 296

“Liste de Brevets” [“List of Patents”] L'Écho des Mines et de Metallurgie (5 novembre 1908)

“Publications de Marriage” Le Gaulois (17 avril 1911)

Firmin Émile Gascouin L’Évolution d’Artillerie Pendant la Guerre (Paris: Flammarion, 1920) pages 29-32

Gascouin L’Évolution d’Artillerie pages 29-32

The figures given by the chart for the German 105mm howitzer come from Hans Linnenkohl Vom Einzelschuss zur Feuerwalze: Wettlauf Zwischen Technik und Taktik im Ersten Weltkrieg (Bonn: Bernard & Graefe, 1996) page 86. Those for the French pieces on their original (non-recoil-absorbing) carriages come from Ministère d’Armament et des Fabrications de Guerre Renseignements sur les matériels d'artillerie de tous calibres en service sur les champs de bataille des armées françaises [Information about Artillery Matériel of all Calibers Serving with French Armies on the Battlefield] (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1918) pages 93-96 and 105-108. Figures peculiar to the pieces mounted on Mourcet carriages were derived from information provided by Leroy Cours d’artillerie page 64.

Bureaucracy and Professional Careers exist to destroy rivals and lay waste the fruits of talent.