The Curious Carriage of Lieutenant Colonel* Mourcet

A path not taken (Part III)

The first post in this series described the development and testing of a remarkable recoil-absorbing gun carriage designed by Léon Mourcet in the 1890s. The second explored a counter-factual scenario, imagined in 1920 by Firmin Émile Gascouin, in which the French Army of the First World War mounted a thousand or so 120mm heavy guns upon carriages of this type. This, the third post in the multi-part article, explores a second possibility, one so radically different that I found it useful to mark counter-factual statements (such as the rank achieved by Monsieur Mourcet) with an asterisk.

In 1935, an instructor at the Artillery School of the French Army [École Militaire d’Artillerie] indulged in a bit of counter-factual speculation. Writing in a textbook for a course on the history of artillery, he mused that, in a world in which the “long recoil” system used in the famous 75mm field gun of 1897 had not been developed, that the French Army would have made extensive use of the carriage developed by Léon Mourcet in the 1890s.1 Building upon this point of departure, we can imagine a French Army of the decade leading up to 1914 in which the field batteries of infantry divisions were armed with 90mm field guns (Model 1877) that had been mated to Mourcet carriages.

Thanks to the use of bagged propellant charges, as well as the relatively slow speed at which the “small mounting” of Mourcet carriages returned to their original positions after firing, the remounted 90mm pieces would not have enjoyed the high rate of fire of the 75mm field gun of our own time line. Nonetheless, they would have been able to send eight or so shells into the air in the minute it took the crew of an unimproved de Bange piece to load and fire a single round.

When combined with the relatively low muzzle velocity of shells fired by de Bange guns, this somewhat slower rate of fire would have prevented the creation of the rafales [gusts of wind] of fast-flying shrapnel bullets that, in the years before 1914 of our time-line, served as the definitive mode of employment of the “seventy-five.” Thus, rather than imagining the modified 90mm piece as a wonder weapon of unprecedented power, French gunners might have taken a more balanced approach to the way they used the piece on the battlefield. In particular, they would probably have made greater use of shells filled with high explosive.

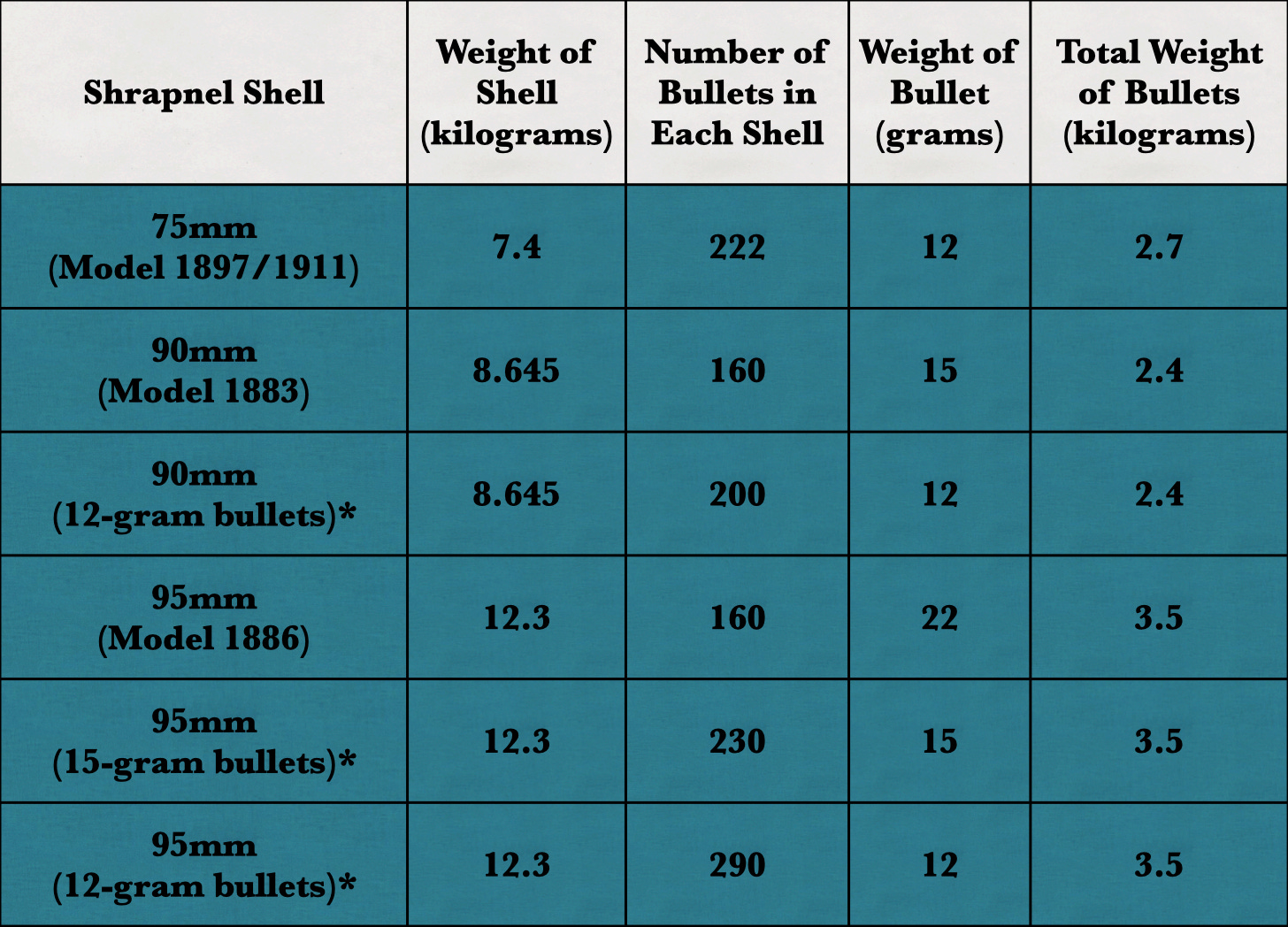

French artillery officers of the Mourcet carriage time line might also have looked for ways to compensate for the relatively small number of bullets released by each volley of shrapnel shells. For example, they might have reduced the size of shrapnel bullets delivered by 90mm shells, thereby increasing the number carried in each projectile. They might also supplement the 90mm guns with Mourcet-mounted 95mm heavy guns.

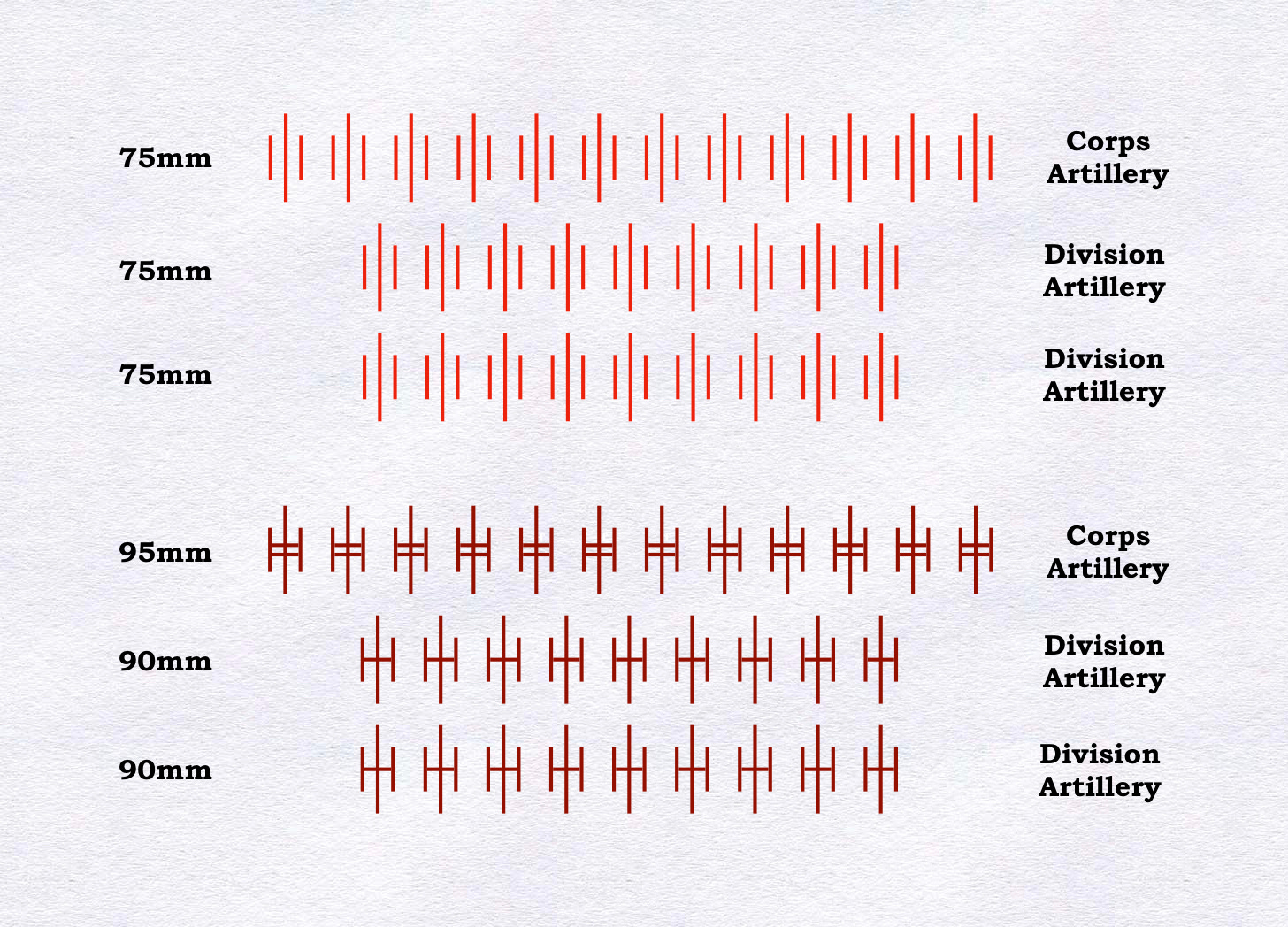

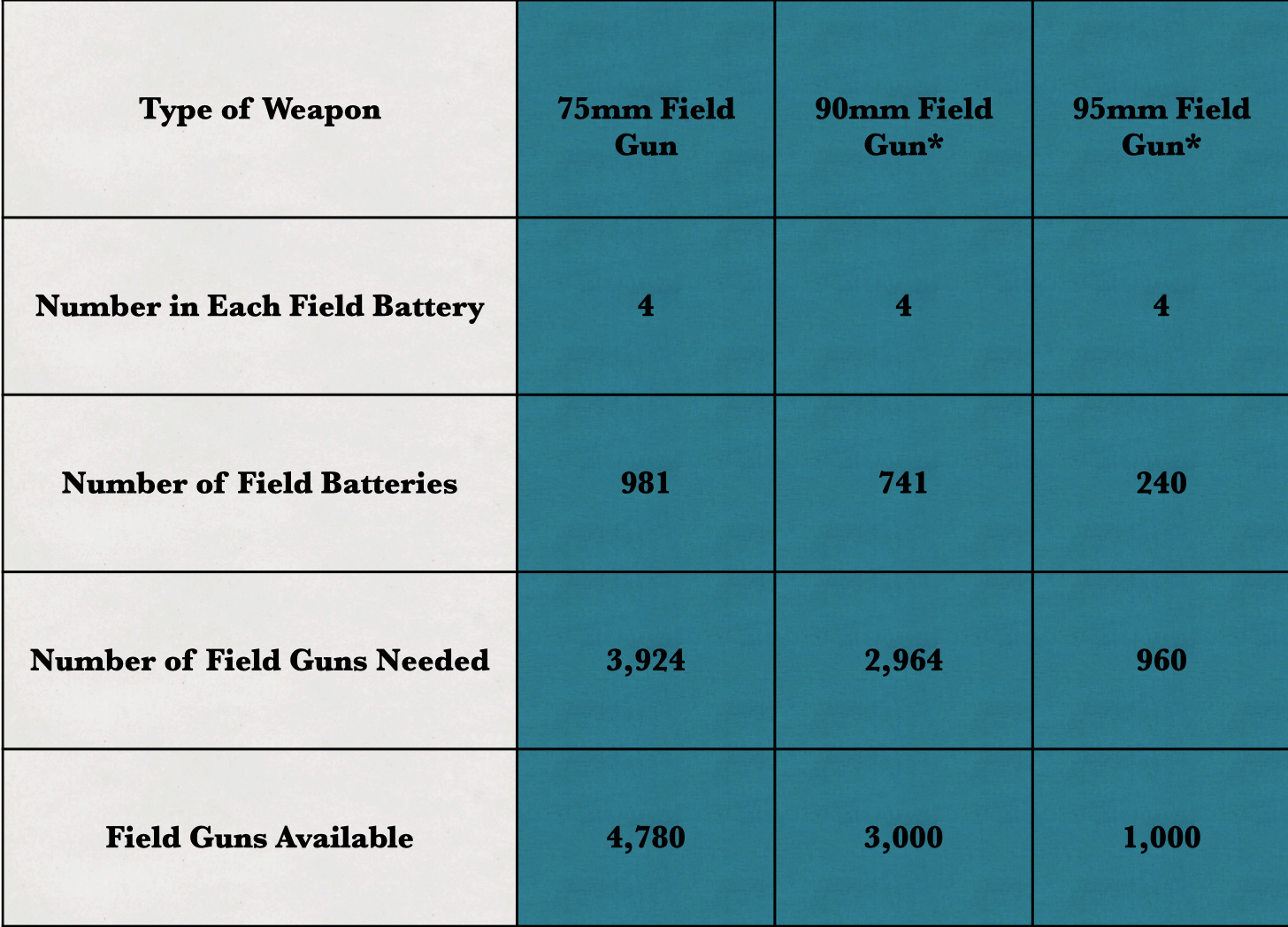

Named for its inventor, Henry Périer de Lahitolle, the 95mm gun began its service as a replacement for the rifled 12-pounder gun-howitzers of the field batteries assigned directly to army corps. Thus, it would have been easy for all concerned to keep the Mourcet-mounted version of that weapon in the same role. Better yet, assigning 95mm guns to the 240 army corps batteries mobilized in 1914 would allow the French Army to reserve 90mm field guns for the 741 field batteries of others sorts. (While most of the latter batteries were assigned to infantry divisions, 51 were allocated to fortresses for service as “sortie batteries” [batteries de sortie].)2

It is also possible that, in a world in which quick-firing field guns did not fire as quickly as the famous 75mm field gun of our timeline, the French Army would have retained the six-piece field batteries of the late nineteenth century. If that had happened, the French authorities might have fielded a smaller number of batteries or manufactured new barrels for Mourcet-mounted field guns. In either event, the French Army of 1914 would have gone to war with corps artillery regiments composed of twelve batteries of re-mounted 95mm Lahitolle guns and division artillery regiments made up of nine batteries of updated 90mm de Bange guns.

For Further Reading:

To Share, Support, or Subscribe:

Capitaine Leroy Cours d'artillerie. Historique de l'artillerie de l'origine à 1914 (Fontainebleu: École Militaire d’Artillerie, 1922) page 62. (I have yet to find any biographical details about Captain Leroy. While catalog of the French National Library provides neither first names nor dates for him, the database of members of the Légion d’Honneur lists a large number of men surnamed Leroy who were born in years compatible with service in the rank of captain in 1922.)

In keeping with the rule that writers of “what if” scenarios should only change one big thing (rather than lots of little things), I am presuming that the French Army mobilized in 1914 of the “Mourcet-verse” would have the same combination of units and formations as the French Army of our timeline. Thus, this paragraph, and the chart that follows, assume the situation described in the order-of-battle chapter in the first volume of the official history of the French Army of the Great War. Les Armées Françaises dans la Grande Guerre, Tome I, Volume 1 (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1936) page 532

Was the Mourcet carriage method ever adopted and could an updated version have current applications?