This is the third post in a substantial series. The following display links will take you to the preceding posts.

The Technical Revolution: Napoleon and Modern Warfare

Georg Wetzell

(Continued)

Field Marshal Baron von der Goltz, the seasoned soldier and eminent military historian, and General von Freytag-Loringhoven, the man who taught military science to the General Staff before the World War, expressed the view that 'Napoleon gave modern warfare its stamp'. The former did this in Heer- und Kriegführung (High Command and Conduct of War) (1901); the latter in his still notable work Die Heerführung Napoleons und die heutige Zeit. (The High Command of Napoleon and Modern Times) (1911).1

Freytag-Loringhoven says that 'Clausewitz transmitted to us the doctrines of Napoleon on the methods of high command, which brought us victory in 1870-1871'. On another occasions he states: 'We acknowledge the soundness of the principles established by Napoleon; it was Field Marshal Count Moltke who demonstrated their importance anew, after they had been forgotten in a long era of peace.'

As to Napoleon’s conduct of the campaign of 1805, Freytag-Loringhoven writes: 'The plan and execution of this operation, which Napoleon had formulated on a grand scale, to this day are a splendid example of the movement of large bodies of troops.'

Finally, he sums up everything into the words: 'Napoleon gave back to the world true conduct of war. Hence it is Napoleon who will retain for all times the glorious title of creator of modern war on a large scale.'

We may add that it was Moltke who perfected the Napoleonic strategy with regard to the command of 'forces organized into independent armies'. Schlieffen contends that Napoleon should have left it to somebody else to master this problem of modern times in its highest form. In one respect, however, even Moltke failed to achieve the heights of the great 'army lord', as Freytag-Loringhoven calls Napoleon, that is, in the employment of cavalry in battle and in pursuit. This has been admitted by Moltke himself.

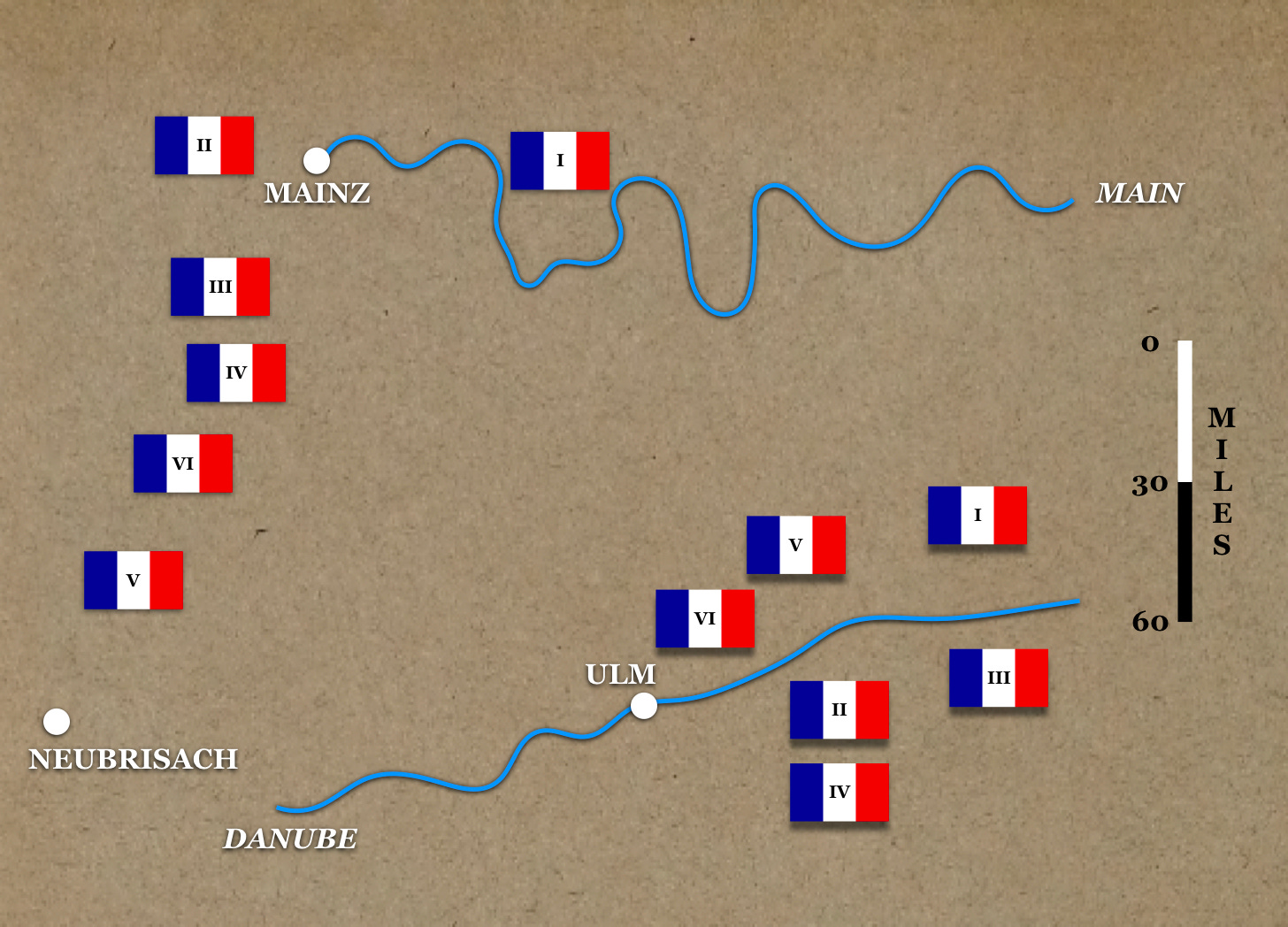

Therefore, in speaking of 'modern military commanders' and a 'modern period of high command,' we must begin with Napoleon. To mention only a few examples, outstanding is his concentration of 1805. Napoleon concentrated his army on more than 150 miles of frontage extending from Neubreisach along the line Mainz-Cologne-Hanover, the same number of miles which the concentration zone of Moltke covered in 1866. From this zone, Napoleon advanced his army in separate stages to the region bounded by the Danube and the Main, where its front had narrowed down to some 60 miles, ready to go into action at any time or to turn into any direction.

The situation was similar in 1806, when Napoleon, his army disposed on a narrow front (37 miles, from Hof to Schweinfurt) but in great depth (from two to three corps on one road), advanced in the direction of Berlin, the capital of Prussia. If we consider that the personal elasticity of Napoleon and the extreme exploitation and application ('activité, activité, vitesse') of his own mental and physical resources as well as those of his staff (six adjutants, ten liaison officers), corps and division commanders, enabled him to achieve so remarkable a 'Cannae' victory as that of Ulm and those of Austerlitz, 1805, Jena and Auerstadt, 1806, Eckmühl, 1809, and others, we may justly say that this 'command' over several distinct armies has never been excelled, for we must bear in mind also that the roads were extremely bad in those days, as were the maps of the theater of war.

While Moltke’s concentration of 1866 resembles that of 1805, that of 1870, as regards width (60 miles) and depth, may be likened to the bataillon carré of Napoleon of 1806 (37 miles). The objectives (Berlin, Paris) as well as the adaptation of the operations to the situation of the opponent and the execution, up to the decisive battle, with an inverted front (Jena, St. Privat) reveal great similarity between the methods of high command of Napoleon and Moltke.

Moreover, the picture of the military leadership of Napoleon is by no means complete with the mention of the 'general’s hill' as Foerster indicates nor with his words: 'On s’engage partout, puis on voit.' ['One makes contact everywhere and then one sees.'] On the contrary, Napoleon was a 'modern strategist' in every sense of the word, as evidenced by the classical answer which he gave one of his most competent generals when that officer asked him how it happened that he invariably anticipated the moves of his opponent; Napoleon replied: 'I never brooded except over the map'.

Goltz refers to the remarkable gift of Napoleon to have kept constantly informed about the changes in the disposition of his corps and divisions. He was endowed with the faculty, which Freytag-Loringhoven demands of every great military leader, 'in his mind to populate the map with troops'. Even Napoleon in his early operations had no choice but to remain in the rear and from there to direct the movements of his army which habitually advanced in separate echelons until the moment of battle. The rides accomplished by his liaison officers and adjutants (up to 75 miles in 24 hours) are truly remarkable, as Goltz and Freytag-Loringhoven repeatedly express themselves.

To be continued …

For the other posts in this series

For more about Freytag-Loringhoven

.

I was unable to find either of these titles in any of the many catalogs I consulted. I therefore wonder if the German titles of the books resulted from double translation. That is, the German titles were first translated into English and then the English titles were translated into German. With that in mind, I suspect that the actual German titles of the books were Die Heerführung Napoleons in ihrer Bedeutung für unsere Zeit and Krieg- und Heerführung. (The links will take you to the entries for those books in the catalog of the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek.)

The radio can free the Commander but enslave his subordinates.

With large armies, if the commander has no idea what his far-flung forces are doing, he cannot exercise any control. If he has radio communications, he may exercise excessive control. Napoleons reliance on the official or formal process of upward reporting from his subordinate commanders, coupled with his use of vertical liaison through his hard-riding adjutants, perhaps gave him the optimal level of awareness and control. I recall that Colonel Elting in his book on the Grande Armee, has good anecdotes and detail about these young officers and their importance to the Emperor.