Welcome to the Tactical Notebook, where you will find more than four hundred tales of armies that are, armies that were, and armies that might have been. If you like what you see here, please share the Tactical Notebook with your friends.

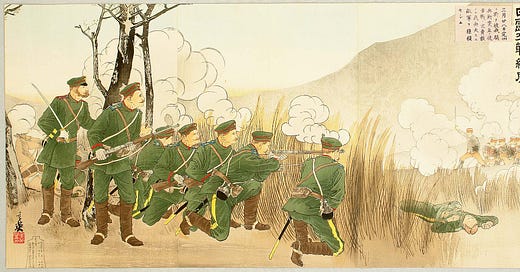

The Russians went even further [than the British]. Only five years after the unfortunate events of the Russo-Japanese War, the Russian General Staff displayed great humility when it published an official history in which nothing was whitewashed and complete objectivity prevailed.1 This was made possible by the dispassionate way in which the defeats in Manchuria are viewed, not merely in the nation as a whole but in the Army as well. As the war in the Far East was never popular, and, indeed, viewed as a failed colonial venture, neither the people nor the Army looked upon the Russian defeat with the kind of shame that every true Prussian feels when he thinks about the Battle of Jena [1806] or every Frenchman experiences when he remembers the Battle of Sedan [1870].

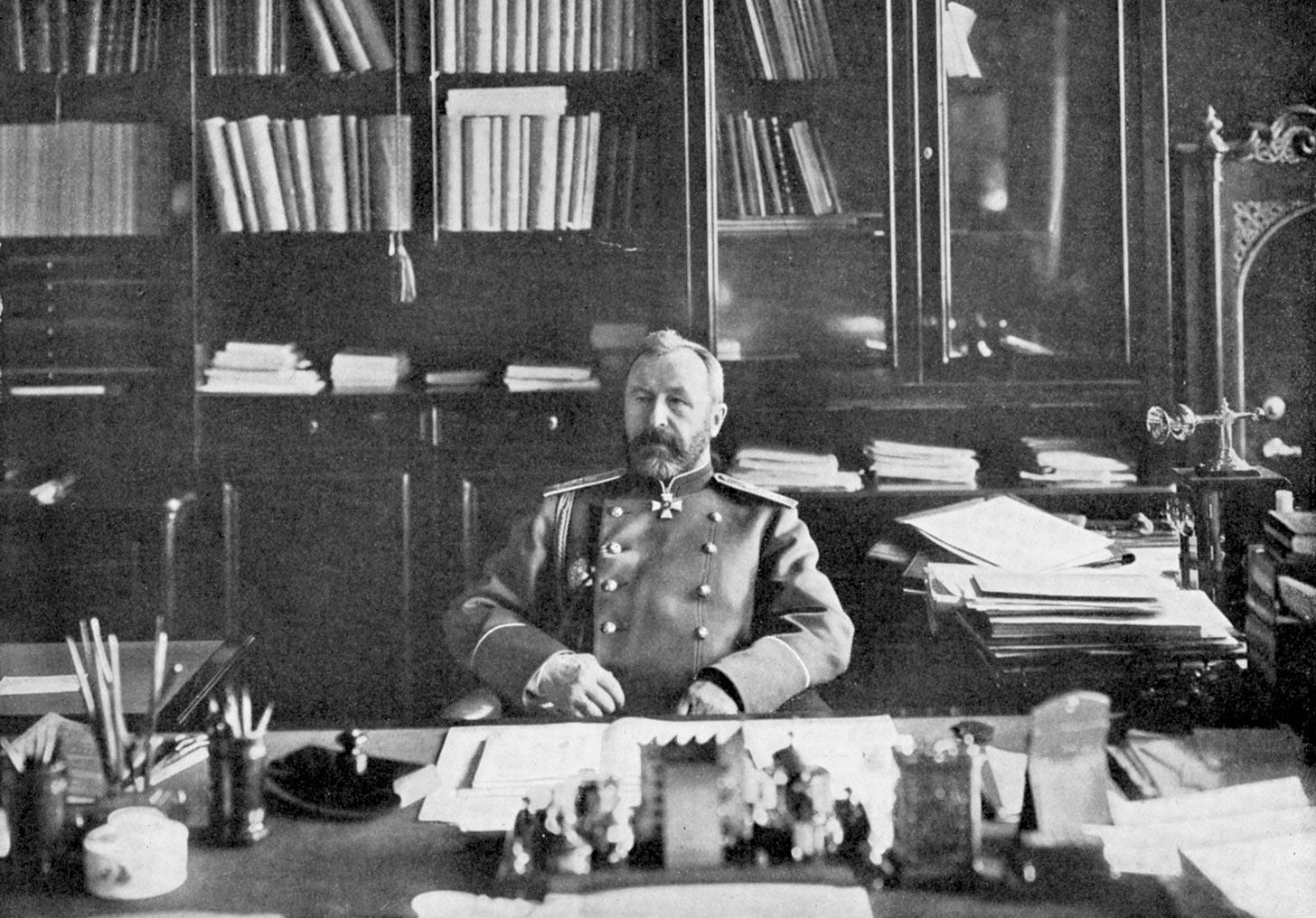

People in Russia, moreover, have long been accustomed to unfettered criticism. Notwithstanding the absolutist character of the regime, as long as one avoided antagonizing the police, a person could say almost anything he wanted. Nowhere was commentary freer, and, at times, more spiteful, than in the salons of Saint Petersburg. Soon after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, one could read in the military journals open criticism of mistakes made [by leaders] and abuses within the Army that had come to light. The book written by General A.N. Kuropatkin, The Russian Army and the Japanese War, provides a first-class example of this phenomenon.

Soon after the end of the war in Manchuria, numerous participants, both those who were well-informed and those who were not, expressed their views in such journals as the Russky Invalid [The Russian Veteran], Voennyj Sbornik [Military Digest], and Razvjedchik [The Scout].2 Indeed, this [abundance of criticism] explains, in part, the rapidity with which the General Staff produced such a large and comprehensive official history. which effectively countered malicious criticism from individuals, including the Supreme Commander [General Kuropatkin], in his prematurely published report to the Tsar.

Written in haste, the Russian official history is not the product of thorough research. Rather, it serves as an extensive and highly valuable, if one-sided, collection of sources. As such, it pays little attention to the perspective of the opposing forces, limiting itself to the brief descriptions of conditions on the Japanese side needed to provide readers with a sense of the whole.

Source: This is the third part of a verbatim translation of Kritik, an article signed by Hugo Baron von Freytag-Loringhoven that appeared in the Quarterly Journal for the Handling of Large Units and Army Studies [Vierteljahrshefte für Truppenführung und Heereskunde] (1913) pages 653-659.

Links to all three posts in this series

To share, support, or subscribe

As I rule, I try to provide links to English-language versions of works that I cite, and, failing that, books in French, German, or Spanish. However, I could not find any translation of the Russian official history of the Russo-Japanese War.

I would like to thank @Dummy for finding, and telling me about, Razvjedchik. Prior to his comment, I spent a lot of time looking for it. (The link is to the Russian-language version of Wikipedia.)

Hello, thank you for the interesting article.

Regarding footnote 2 - Raswjädschik looks very similar to Razvjedchik, quick search brought me to this Russian journal active in period 1889-1917 https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%A0%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%B2%D0%B5%D0%B4%D1%87%D0%B8%D0%BA_(%D0%B6%D1%83%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%B0%D0%BB) I hope it helps