Continued from …

The Technical Revolution: Napoleon and Modern Warfare

Georg Wetzell

(Continued)

The book is introduced by an article entitled 'The Modern Military Commander', by [the retired] Lieutenant Colonel Wolfgang Foerster, President of the Kriegsgeschichtliche Forschungsanstalt des Heeres (Historical Research Institute of the Army).

In it I had expected to find the conclusions drawn from the descriptions of the various commanders that are contained in the subsequent text. This is not so, however. Although I consider the basic thoughts expressed in the ingenious introduction highly noteworthy, they represent views in part that are contrary to my personal experiences in war and the lessons which I have derived from the study of military science. Therefore, I believe it to be worth while to examine these points.

The article begins with the statement that the 'revolutionary effect' of the progress made in the field of technique produced a completely new type of military command; that a 'technical revolution' created the modern military commander; and that his era dates back to the abdication of Napoleon.

In my opinion, there has been only one technical revolution in warfare to speak of, the invention of gunpowder. It is true, the invention of gunpowder led to a complete revolution of the means of warfare (armament) and, in turn, of the conduct of war (tactics and strategy). And yet, this revolution did not spread 'like a storm', but took place 'gradually'.

The technical development of all close combat (infantry) and distant combat (artillery) arms, from the end of the Thirty Years’ War to the present day, during which mechanical production has taken the place of handwork, has by no means a 'revolutionary' character. Several centuries went by before the steadily improved muzzle loader became a breech-loader (needle gun), and the latter — upon a corresponding perfection of the ammunition (metal cartridge) — in turn developed into a rapid-fire repeating rifle which uses smokeless powder. Even the development of the machine gun was not 'revolutionary'; the same goes for the jump from the muzzle-loading cannon of Frederick the Great to the modern rapid-fire gun equipped with recoil system and armor shield and to the automatic (antiaircraft) gun.

Therefore, though there was no technical 'revolution', we may speak of an 'evolution' in which, it must be noted, the tactics frequently exercised a decisive influence upon the technique. For instance, the technique was influenced by the new method of infantry combat (tirailleurs) introduced in the American War of the Revolution over a century ago and used again on a greatly increased scale by the national army in the French Revolution. Tactics of this kind presupposed shoulder arms which possessed greater accuracy of fire and which could be handled with greater ease than the old guns.

Very similar conditions may be noted with respect to the artillery, of which the tactics constantly demanded increased effect, range, mobility and so on. Every form of progress made in the field of ordnance implies changes in the methods of combat and in the tactical conduct of troops to which strategy has always conformed. On the other hand, the great fundamental principles of high command have had less influence on the evolution of technique and tactics.

Count Schlieffen expresses the opinion that these principles have remained intact ever since the days of Hannibal. As regards tactics, however, Napoleon believed them to be subject to a fundamental change every ten years. It is remarkable that Field Marshal Count Moltke, whom Foerster in his review places into the foreground — and justly so, makes no mention whatever of an influence of any kind of 'technical revolution' upon the methods of high command.

Nor has the steam power of the railroad or the power of the gasoline engine in the form of highly mobile motor vehicles had an 'revolutionary' effect upon the conduct of high command. On the contrary, the high command has logically applied mechanical power toward lending the various means of warfare greater mobility. In the era of Moltke, railroads, took the place of the large wagon trains which Napoleon had used to carry out the strategic concentration of his armies. The motor vehicle did not gain its place in warfare until the World War.

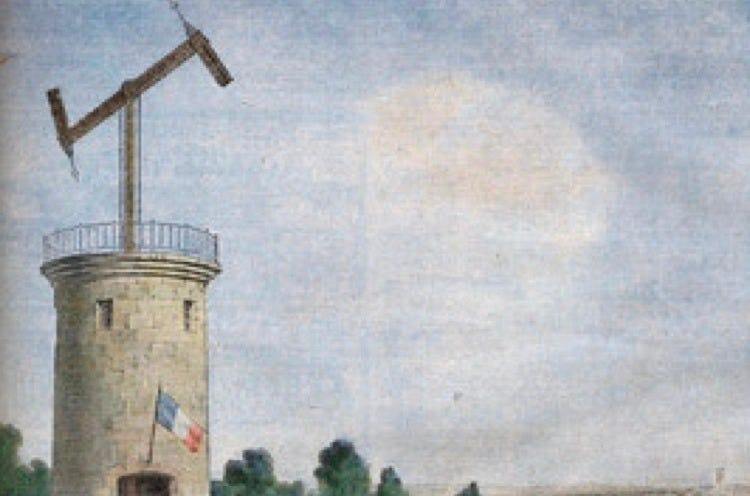

The same applies to the means of signal communication which are so important for the practical command of troops. The evolution from the optical telegraph used by Napoleon to the Morse telegraph employed by Moltke took quite a span of time and required a very gradual development of this new technical means of command.

The use of the telephone for military purposes did not materialize until the turn of the century, and then the progress was slow and by no means 'revolutionary'. Even the radio fails to reveal, upon close inspection of its development, any 'sudden' adaptation to the military purposes. Incidentally, we must bear in mind that, at the time of Count Schlieffen, the German Army of a million men in peace included only three signal battalions. The World War demonstrated that, although the peace organization of these vitally important 'command units' was tripled, their strength, inclusive of their mobile elements, was wholly inadequate to carry out the missions confronting them.

In summarizing our thoughts, we may say that in all wars both sides have made use of all available technical aids. However, it devolves upon the high command to exploit the technical development of the arms properly and to apply the technical aids to strategic purposes. Therefore, I can neither agree with the conception that the 'modern age of military commanders' began with a 'technical revolution' nor concur with the claim that the 'modern period began with the departure of Napoleon.'

On the contrary, with regard to the latter conclusion, I share the views expressed by other military historians, such as Clausewitz, the greatest war philosopher of all times, Moltke, Schlieffen, Goltz and Freytag-Loringhoven; it is the contention of these men that the 'modern high command' not only began with Napoleon, but that it was he who introduced it. This modern method was first put into practice by the large French units of conscripts, which made it necessary to organize large mixed units: infantry divisions, cavalry divisions, army corps and cavalry corps. On the advance, these units would frequently be widely separated from each other, sometimes several columns following each other on the same road (1805 and 1806), and as a rule take up a formation in line when going into battle.

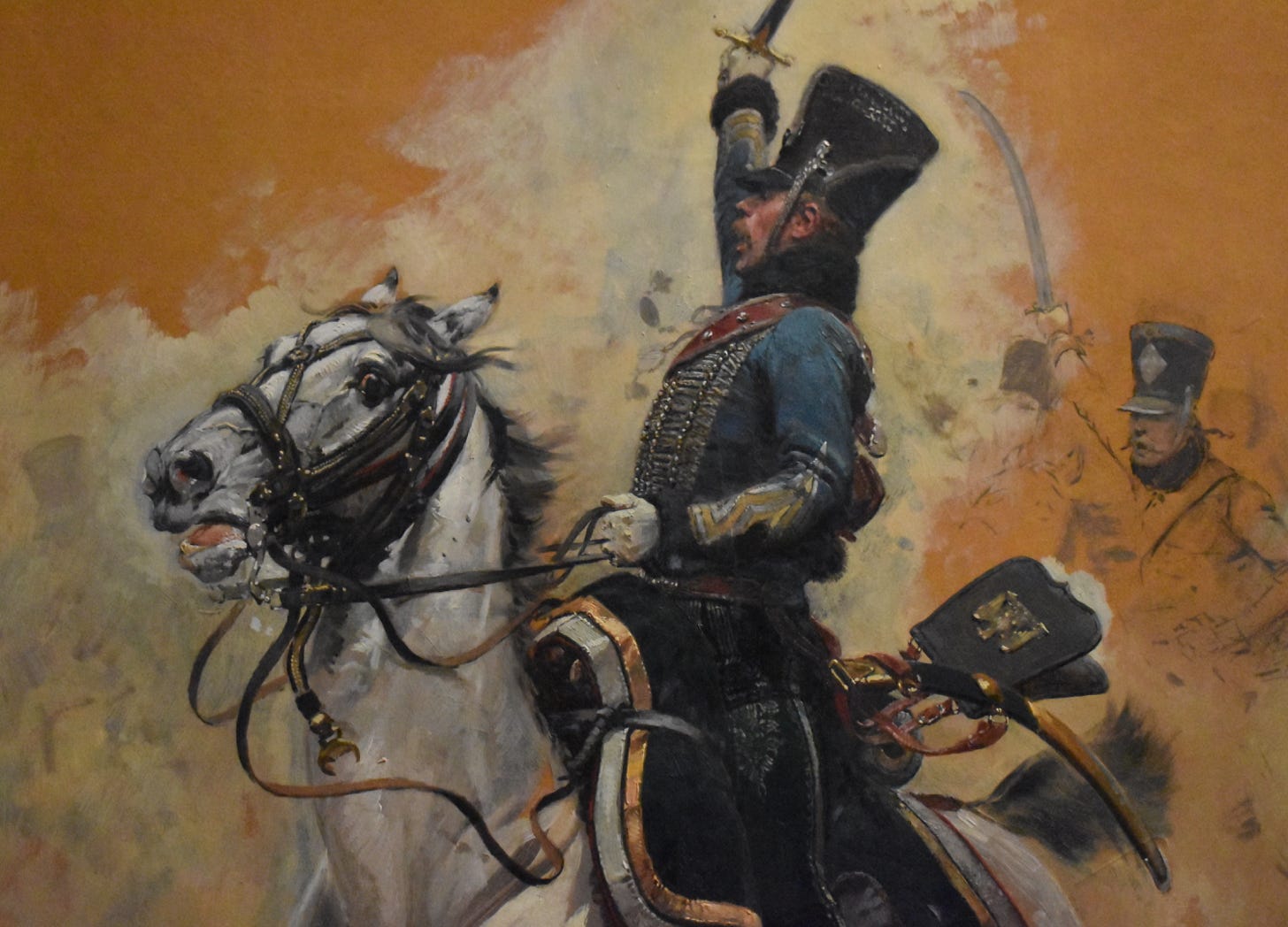

It is true, the tactics employed by these units in combat had changed completely from the more parade-like evolutions of the period of Frederick the Great. The Napoleonic method of conducting reconnaissance far in front by large independent cavalry units (divisions and corps) was an innovation. That holds true also of the artillery concentration in battle (large batteries). There were few changes in the employment of cavalry in battle during the period from Frederick the Great to 1870. No army commander has ever been able to equal the ingenious manner in which Napoleon used his cavalry for pursuit at the conclusion of a battle.

To be continued …

Overview of this Series

Source

The text of this series comes from the translation made at the US Army War College in 1939.

You wanna know who should really run the TOC&ALOC?

An NYC Manhattan office building maintenance manager who understands infrastructure, power, water, communications, networks, the infrastructure of a building, even BTW steam turbine power and heat (still used in NYC).

Not “STEM” majors lol.

Yes, he’ll know where the fsking units are, if anyone does…

That’s the proper XO. 😘

If the telephone chained the commander, the radio freed him.

Or COULD if he and these monstrous Command Pustles, Tactical Occlusion Carbuncles , Cosplay of ComicCon and Orwell as NASA knockoff could be separated.

We don’t even need these staffs, our Commanders are hardly spoiled aristocracy or Politicians made Generals needing to be hand held through war…