On the eve of the Second World War, two retired officers - Georg Wetzell and Wolfgang Foerster - debated the question of whether changes in technology had materially altered the role of senior commanders. In the course of conducting this debate, which took place in the pages of two military journals, Wetzell and Foerster provided their readers with a short course in operational art.

The debate began when the Military Weekly (Militär Wochenblatt) published a review in which Lieutenant General Wetzell both praised the main body of the work in question and took issue with a forward provided by Lieutenant Colonel Foerster. In this, the first post in a series that offers the entirety of this exchange, Wetzell runs a warm-up lap.

The Technical Revolution: Napoleon and Modern Warfare

Georg Wetzell

The Deutsche Gesellschaft für Wehrpolitik und Wehrwissenschaften (German Society for Military Policy and Sciences) has recently come forth with a valuable book. Called Heerfuhrer des Weltkrieges (Military Commanders of the World War), this work, published Mittler und Sohn, merits the greatest attention.

In the book, all army commanders of the Central Powers and their opponents are subjected to an unbiased and high-minded analysis. The attractive and instructive feature of this eminent volume of military history is the great panorama of the World War, especially the decisive strategic problems confronting the high commands, which the fascinating characterization of the various commanders present to the reader. Dealing with both friend and foe, this study permits any reader to form an independent opinion.

The description of the ten commanders, from the younger Moltke, Joffre, Falkenhayn, Conrad von Hötzendorf, Alexeiev, Enver Pasha, Cadorna, Haig, Foch to Hindenburg-Ludendorff, constitutes the mosaic of this imposing World War picture.

While it is not the purpose of the present discussion to go into the details of the book, it is hoped that all future commanders as well as any other student of military history will read the book and benefit from it.

On one point, concerning the British Expeditionary Force (B.E.F.), I differ with the views expressed in the book (about Field Marshal Douglas Haig). The book represents the opinion that Haig had the right idea in proposing to withhold the support of the B.E.F. until it had been strongly reinforced, that is, to commit it to action late in the autumn of the year instead of at the outset of the War.

Actually, the B.E.F. saved the French Fifth Army (Lanrezac) at the Sambre and Meuse (August 23, 1914) from a serious defeat which might have decided the outcome of the war then and there. Besides, we must not forget that the B.E.F. (two corps and one cavalry division) played a vital part in creating the gap between the German First and Second Armies on the Marne (September 5-9, 1914); or that, without its support, [the French Commander-in-Chief General Joseph] Joffre could scarcely have launched his counter-offensive. Strategically speaking, the small B.E.F. acted as a life-saver at the beginning of the World War, despite the fact that its command was not what we would call exemplary.

Note

In August of 1914 the British Expeditionary Force was the smallest field army on the Western Front. Notwithstanding its size, the BEF played an important role in preventing German victory in the critical months of August and September,1914.

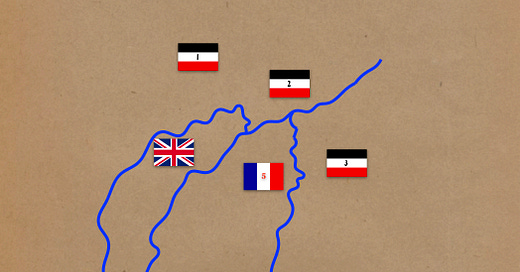

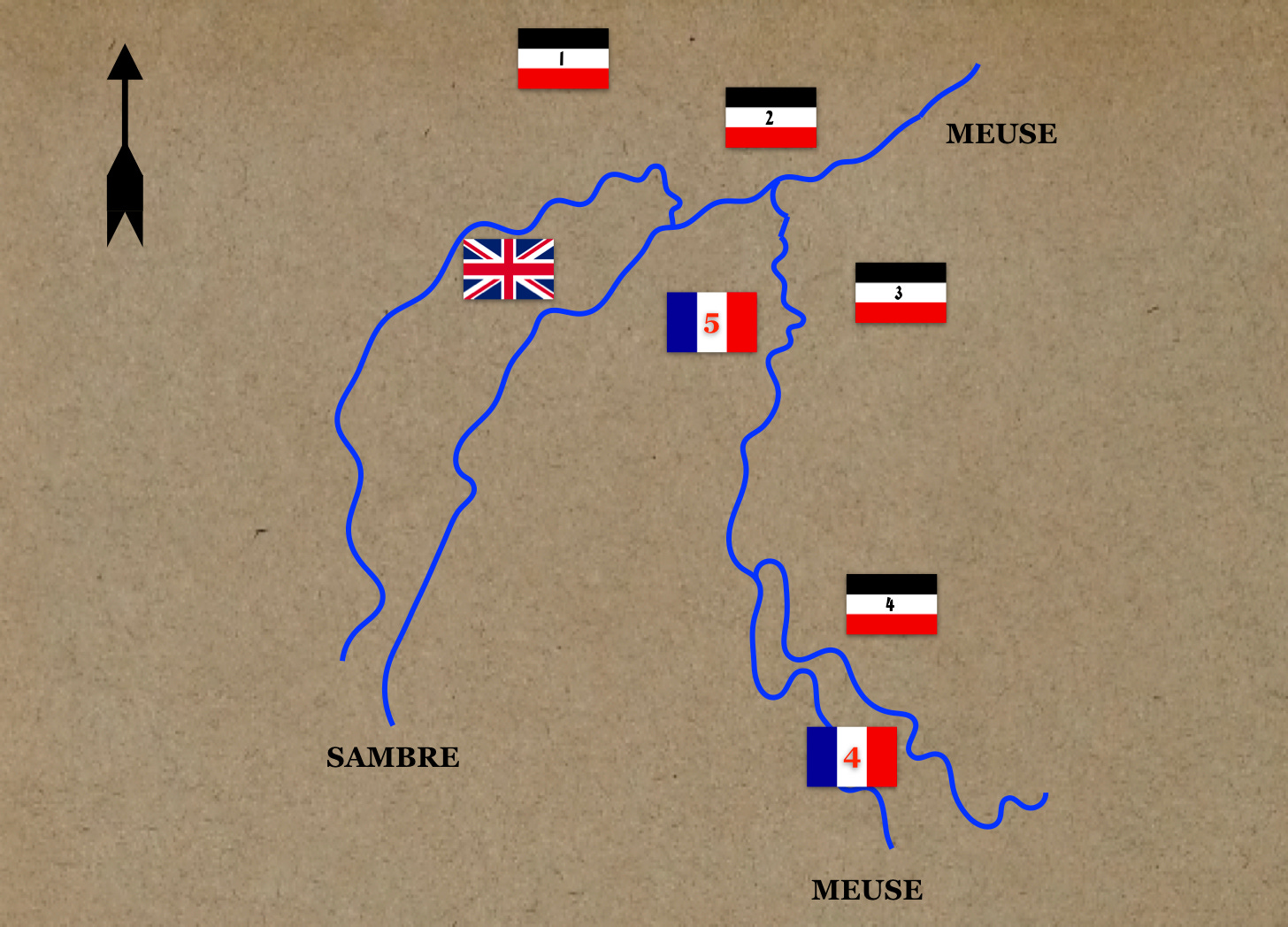

On the 23rd of August, 1914. The French Fifth Army found itself in a difficult position. With its forces pushed forward into the ‘peninsula’ formed by the junction of two rivers (the Sambre and the Meuse), it faced a three German Armies. To make matters worse, the neighboring French Fourth Army, locked in combat with its German numbersake, could do little to help.

As might be expected, the Germans tried to exploit this advantage with a simultaneous attack by three field armies, neatly numbered, from north to south, as the First, Second, and Third Armies.

The main effort of this maneuver lay with the German First Army, which attempted to envelop the French Fifth Army from the northwest, thereby preventing its retreat.

Happily for the Entente (and sadly for the Germans), the German First Army found its path blocked by the British Expeditionary Force, which held long enough to allow the French Fifth Army to escape.

Source

The text of this series comes from the translation of the component articles of the debate that was made at the US Army War College. An ink-and-paper copy of this work can be found in the library of the US Army Heritage and Education Center. (The catalog of that splendid repository lists George Wetzell as the sole author and The Modern Military Commander as the title.)

Series

This post publishes part of a much longer work. For links to other parts and an overview of the series as a while, please see