This is the fourth part of a long series. The links pasted below will take you to the three posts that precede it.

The Technical Revolution: Napoleon and Modern Warfare

Georg Wetzell

(Continued)

In his illustration of the 'modern military commander,' Foerster attempts to deduce from the Schlachtenlenker (director of battles) (Napoleon) and the Schlachtendenker (planner of battles) (Moltke) that lonely general who, far behind the front, sits at his desk 'in a warm and well lighted room' and broods over his maps, the commander ‘whose preparatory and introductory work is accomplished in the period leading up to the operations, usually long before war breaks out’, and who announces his decisions by means of the telephone, telegraph, and radio. To use an expression coined by Freytag-Loringhoven, I would call this type the 'learned strategists’. Yet neither had Moltke anything in common with this type, nor did the World War produce it.

The evolution of the 'military commander at the desk' is mentioned first in connection with the leadership of Moltke. Indeed, the campaigns of Moltke distinguished themselves from previous campaigns, especially from that of 1866, when the concentrated armies for a long period were directed from the rear by telegraph, and mutual contact was purposely avoided. It is true also that 'the organization of the armed forces into separate armies minimizes the threat of the defeat of any one of those armies'.

Nevertheless the history of the French and Russian armies in the World War, 1914, reveals a different picture (Lorraine, Sambre, Meuse, St. Quentin; Tannenberg, First Battle of the Masurian Lakes). Even in 1866 and 1870-1871, the German armies were seriously threatened on various occasions.

In 1866, it was necessary to direct the armies from a point far in the rear (Berlin) with the newly invented technical aid of the Morse telegraph; this was due, above all, to the fact that Moltke and his King could not join the main forces in Bohemia until relatively late, since the High Command in the capital was awaiting the outcome of the struggle with Hanover and the development of the situation in Western and Southern Germany.

Napoleon employed his far more unwieldy optic telegraph in a similar manner (1805, 1809.) It is to be noted further that, as early as 1813, the operations which led to the decisive Battle of Leipzig were executed by separately functioning armies: the Austrian Main Army in Bohemia; Blücher (Prussian-Russian forces) in Silesia; Bernadotte and the Army of the North (Prussian-Swedish forces) in Brandenburg.

Schlieffen comments: 'The strategy employed by the Allies, the concentration of separate armies on the battlefield, surpassed all expectations.' General Erfurt writes: 'It was the first time in military history that a high command succeeded in joining on the common battlefield several armies approaching separately from opposite directions.' He fittingly calls Leipzig a 'milestone on the path of the evolution'.

In as much as Foerster uses only Moltke’s concentration of 1866 as evidence of a 'modern high command', it might appear as if the strategy of Moltke consisted in attacking the opponent from a broad concentration, while keeping the individual armies separated, in order to 'achieve the optimum from that strategy, namely, after a final short march to commit the armies to action simultaneously from several directions against the hostile front and flank'.

Moltke drew this conclusion, in 1869, from the operations that led up to Königgrätz. Although undoubtedly true from a theoretical point of view, it was not the content of the military genius of Moltke. In my opinion, this genius is much more aptly characterized by Moltke’s own words: 'Strategy is a system of expedients.' By no stretch of the imagination can the high command of Moltke be pinned down arbitrarily to a preferred basic form of concentration.

This is shown most emphatically by the difference in the concentration of 1870, which Foerster fails to mention. Here Moltke concentrates 400,000 men in a zone barely 60 miles wide (Saar Rhine) but echeloned in great depth, on a plan similar to that which Napoleon followed in 1806.

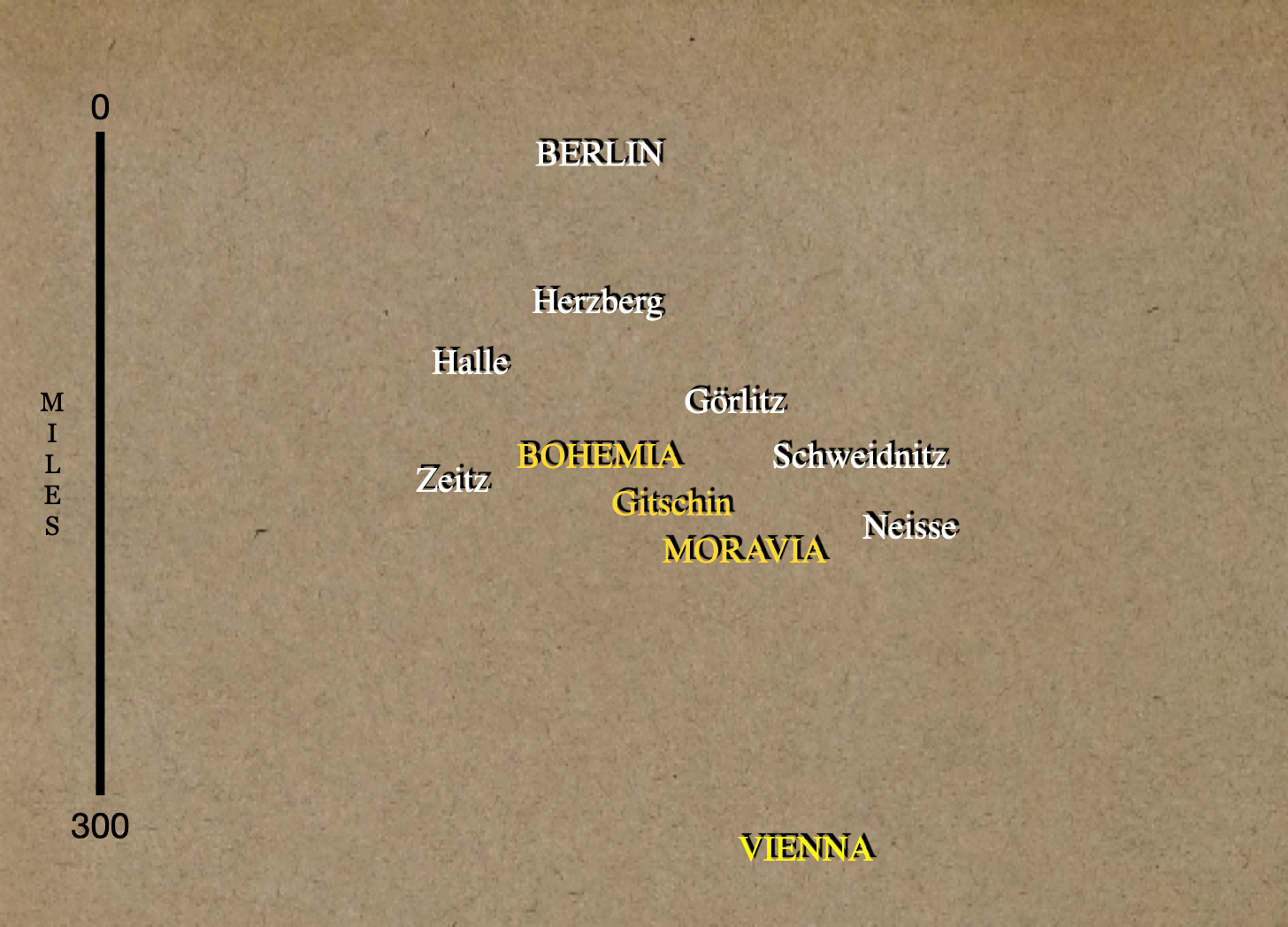

Moltke himself stresses the simplicity of both the concentration of 1866 and that of 1870. He states that both forms were prescribed by the geographical situation and the technical development of the railroads. In 1866, these conditions demanded the debarkation of the Prussian Army along the line Zeitz-Halle-Herzberg-Görlitz-Schweidnitz-Neisse and a broad zone of concentration. In 1870, the situation called for a narrow zone of concentration in the Palatinate, between the Saar (Moselle) and the Rhine.

With regard to the concentration of 1866, Moltke says: 'The question whether the still divided contingents would have to march on the periphery in order to effect a closer union, or whether they could accomplish this by operating toward the center, depended entirely upon the decision whether to fight the war by defensive or offensive means’. Moltke expected Austria to have the advantage in mobilization and counted on a possible joint Austro-Saxon attack in the direction of Berlin. It was not until the news reached Berlin that the Austrian forces were divided, small elements located in Bohemia and the main forces occupying Moravia, that orders were issued to make a concentric advance in the direction of Gitschin.

The main forces (Army of the Elbe and First Army) were to enable the Second (Silesian) Army to debouch from the difficult mountain region of Glatz. The military genius of Moltke clearly visualized the danger of this bold operation. The slow progress of the Army of the Elbe and First Army and the many unfortunate dispositions of the latter, such as the one created by the reverse of Trautenau, provoked a serious crisis. However, as in most bold strategic operations, this crisis was overcome by the fact that 'the tactics came to the aid of the strategy' (an expression of Moltke).

The high standard of the instrument of warfare (improved armament of the infantry: needle gun and modern training) and the energy demonstrated by some of the subordinate commanders (Steinmetz) surmounted the difficulties that had arisen. However, Königgrätz, as well as subsequently Metz and Sedan, and the successful operations of the World War, especially Tannenberg and Flitsch-Tolmein [Caporetto], also belong among those grandiose strategic ideas, of which Count Schlieffen says that 'the enemy must contribute his share in the accomplishment of a defeating blow'. The same as Hannibal needed a Terentius Varro at Cannae, so Moltke required a Benedek, in 1866, a Bazaine and MacMahon, in 1870, and Ludendorff, a Samsonov [at Tannenberg in 1914.]

In his work Moltke-Benedek-Napoleon, Major Krauss (the well-known General Krauss of the World War) correctly states that, if the Austrians had possessed a better high command in 1866, they could have exploited the gap between the Prussian armies and would have been more successful.1

Field Marshal Count Moltke, the greatest German general of modern times, knew no preference for any kind of strategic principle. He was likewise free from any confining theory in the execution of his high command. Ludendorff resembles him in this respect. Field Marshal Baron von der Goltz may be justified in stating that, above all, Moltke in war neglected the theoretical principles which he himself had established in peace.

To be sure, the result of the campaign of 1866, which reached its climax in the Battle of Königgrätz, is the strategic ideal which a military commander can possibly attain. However, it does not constitute the basic content of the art of the high command of Moltke. I conceive it rather as the faculty of this military genius to adapt himself readily to the hostile situation of the moment and the extraordinary energy which he displayed in the execution of whatever decisions he would make. Moreover, in the execution of his decisions, Moltke was always there personally where he should have been not 'far in the rear at a desk’, but out in front with the troops, at the main effort [Schwerpunkt].

End of Part I. The series continues with Field Marshal Count Moltke, Schlieffen, and the World War

Guide to the Series

Perhaps I have a faulty memory of history, but my recollection and research is that the Battle of Königgrätz was not a stunning example of strategy or operational art. The battle began as a surprise meeting engagement due to mutually faulty reconnaissance with both sides holding not so favorable positions. True, the Prussians inflicted a severe defeat on the Austrians, but Moltke failed to pursue closely, much like Mead after Gettysburg, and allowed the Austrians to regroup at Olmütz (Olomouc) in Moravia. The war was ended when a truce was arranged at Nikolsburg (Mikulov) on July 26 and not by a follow on decisive battlefield victory. What am I missing?

With regard to the comments on Steinmetz. Wasn't Steinmetz insubordinate to the point hat he nearly wrecked von Moltke's palns on more than one occasion and it was only the flexibility of von Moltke and the other Corp/Army Commanders that salvaged the near train wrecks?