Heavy Field Howitzers (IX)

Armies of the First World War

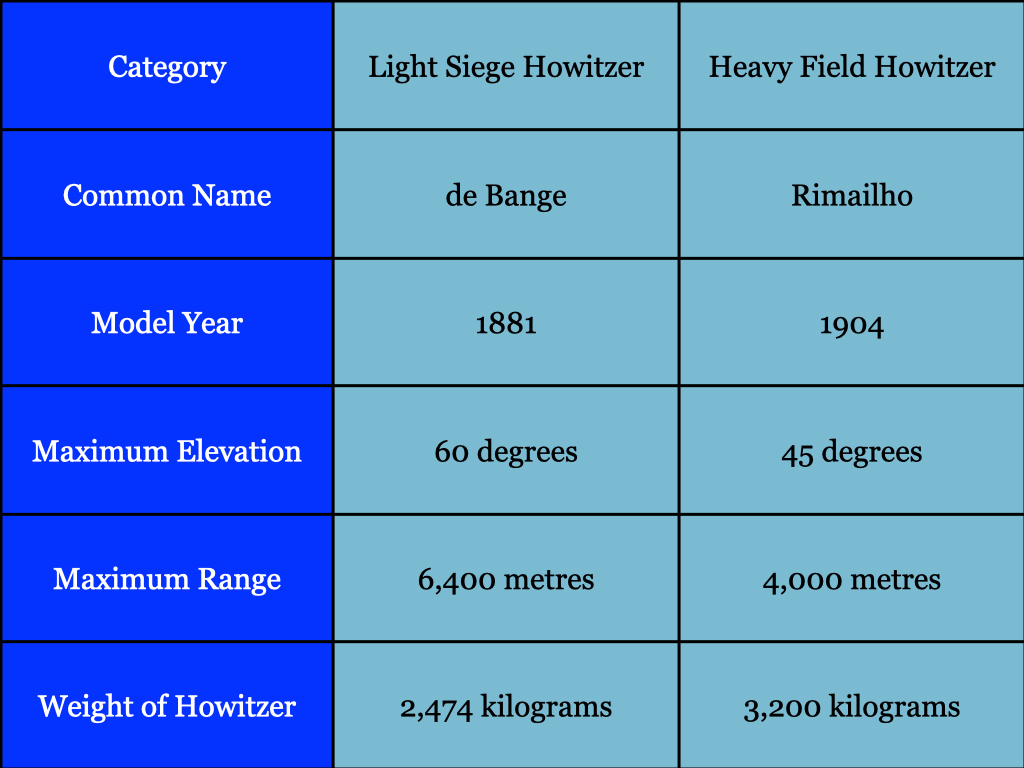

In 1898, Émile Rimailho of the French artillery proposed the design of a heavy field howitzer with a hydro-pneumatic on-carriage recoil-absorbing mechanism similar to the one that gave the 75mm field gun of 1897 such a revolutionary rate of fire.1 Unfortunately, Rimailho’s superiors were less interested in creating an entirely new weapon than in updating the French Army’s existing stock of 155mm light siege howitzers. Thus, while they approved Captain Rimailho’s project, they required him to make use of barrels belonging to the “short gun” (canon court) of the de Bange system adopted in 1881.

The weapon that resulted from this ill-conceived marriage was “neither fish, nor fowl, nor good red herring.” On the one hand, the Rimailho howitzer possessed neither the stability nor capability for high-angle fire required of a true light siege howitzer. On the other, it lacked both the mobility and the range of a proper heavy field howitzer. What was even worse, the weight of the repurposed barrels put a great strain on both the recoil-absorbing and breech-opening mechanisms of the piece. Thus, whenever a full strength propellant charge was used in a Rimailho howitzer, one of the aforementioned subassemblies stood a good chance of breaking.2 (This defect reduced the maximum effective range of the piece from a respectable 6,300 meters to a sub-par 4,000 meters.) 3

The difficulties experienced by the Rimailho howitzer strengthened the hand of those within the French Army who were already opposed the acquisition of heavy field howitzers of any description. In some cases, this opposition was part and parcel of soixantequinzeboutisme, the belief that the 75mm field gun should be the heaviest artillery piece employed by French field armies.4 In others, dislike for heavy field howitzers was the corollary of a desire to arm French heavy artillery units with modern heavy guns.

The first point of view was most influential in the first few years of the 20th century, when the 75mm gun was still a recently unveiled wonder weapon that other armies were rushing to imitate. The second point of view, which placed great value upon the ability of heavy guns to fire at distant targets, never managed to garner the same degree of public attention as soixantequinzeboutisme. In the years immediately preceding the outbreak of World War I, however, it slowly gathered support within military and political circles. By the end of 1913, this desire to provide French field armies with large numbers of quick-firing heavy guns had resulted in a program to build 340 such weapons.5

A 'buffer' is a device that absorbs the rearward forces generated by firing. A 'recuperator' is a device that helps the barrel assembly of an artillery piece return to its original position. A 'hydro-pneumatic' recoil mechanism is one in which a liquid-filled buffer uses the mechanical energy produced by recoil to compress the gas in a gas-filled recuperator. When the rearward movement is complete, the gas in the recuperator begins to expand, thus providing the power needed to send the barrel assembly back to its starting point.

The technical data for the Model 1881 de Bange light siege howitzer comes from Jules Challéat, L'artillerie de terre en France pendant un siècle : histoire technique (1816-1919): Tome II, 1880-1910 (Paris: Charles-Lavauzelle, 1935), pages 16 and 17. The technical data for the Model 1904 Rimailho heavy field howitzer comes from Hans Linnenkohl, Vom Einzelschuß zur Feuerwalze (Koblenz: Bernhard und Graefe Verlag, 1990), page 92.

The most prominent of the soixantequinzeboutistes were Hippolyte Langlois (1839-1912) and Alexandre Percin (1848-1926) Well before the unveiling of the 75mm field gun of 1897, General Langlois anticipated the development of quick-firing field pieces with the first edition of his L’Artillerie de Campagne en Liaison Avec les Autres Armes. The definitive expression of his soixantequinzeboutisme, however, would have to wait until his Questions de Défense Nationale, (1906) General Percin, who served as Inspector General of Artillery from 1907 to 1911, promulgated his opinions on this subject in several books. These included La Manœuvre de Lorlanges Exécutée par le 13° Corps le 12 Septembre 1908, (1909); La Liaison des Armes (1909); L’Artillerie aux Manoeuvres de Picardie (1911) and L’Artillerie au Combat: Révision du Règlement de Manoeuvre (1912)

A description of this program can be found in Louis Baquet, Souvenirs d’un Directeur d’Artillerie, (Paris: Charles-Lavauzelle, 1921), pages 120 and 21.