When, in June of 1919, the government of the new German republic signed the Treaty of Versailles, it promised to divest itself of the two thousand or so heavy trench mortars it had inherited from the armies of Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, and Württemberg. At the same time, it received permission from the victorious Allies to provide each of its twenty-seven infantry regiments with a company armed with Minenwerfer of more modest dimensions.

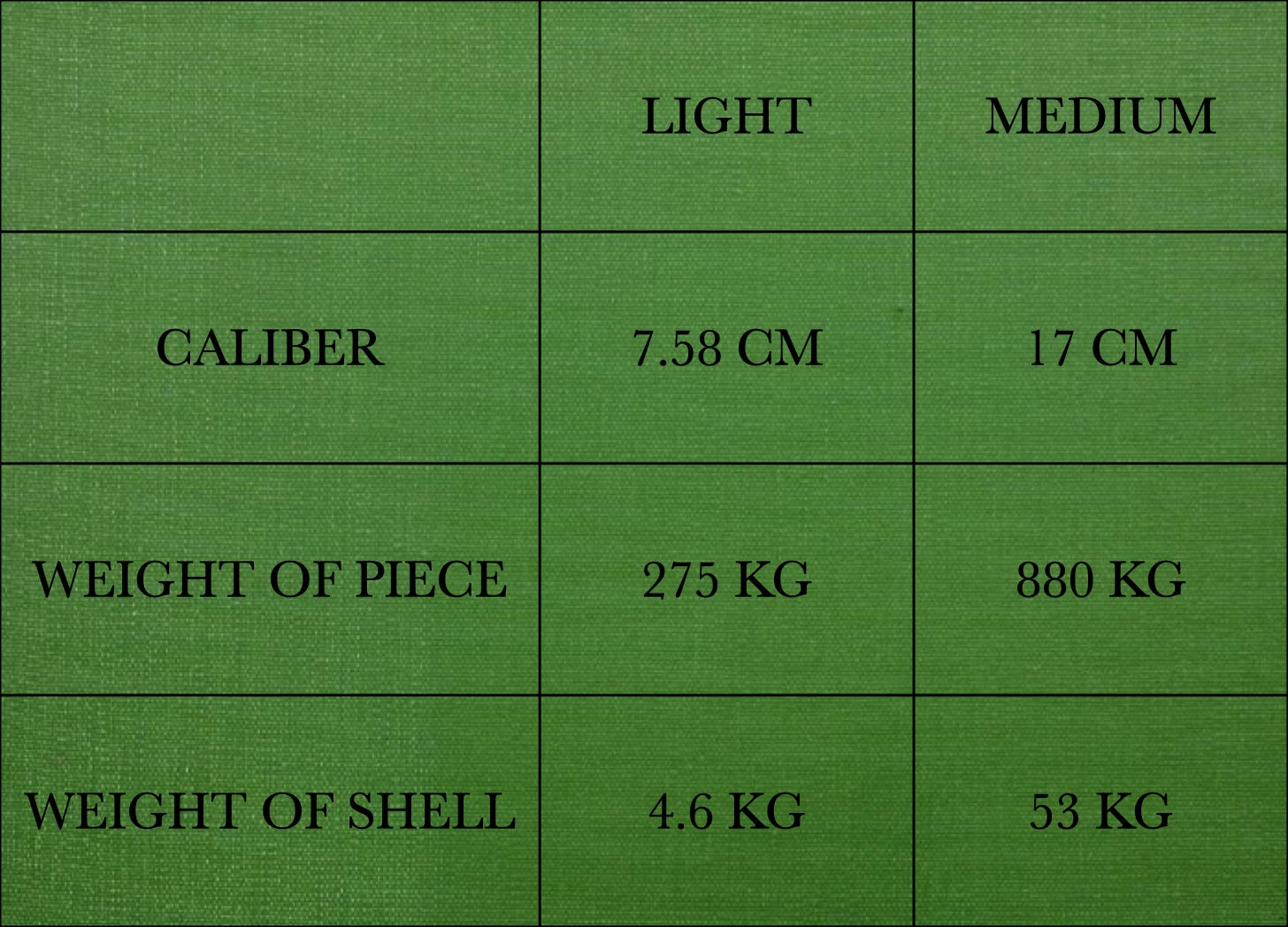

Each of these Minenwerfer companies, which formed the thirteenth companies of their respective regiments, fielded four two-piece firing platoons. Three of these platoons wielded light Minenwerfer of a type introduced in 1916. Mounted on a carriage adopted in the last year of the war, these multipurpose weapons could be employed as mortars, escort guns, or anti-tank weapons. The fourth platoon operated medium Minenwerfer of a model first issued in 1916, weapons of greater weight and power that could only be used in the manner of a trench mortar.

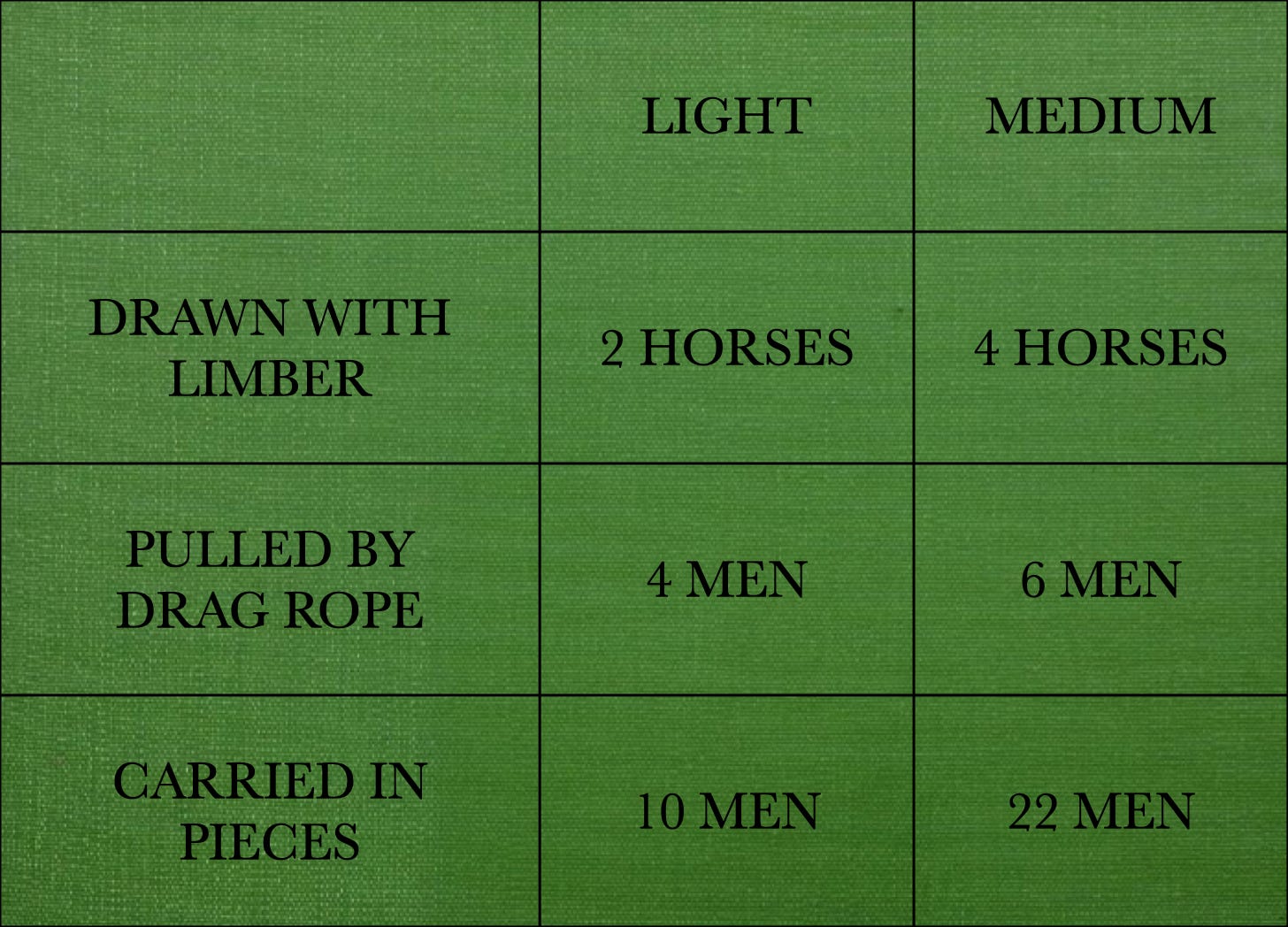

When the ground and quadrupeds obliged, a Minenwerfer traveled with the aid of a horse-drawn limber. Failing that, the men of a Minenwerfer crew used drag-ropes and elbow-grease to move their piece from place to place. When this was not possible, they broke their weapons into portable components and, with the help of wooden poles and a working party, carried them to their firing positions. (The links will take you to photos on the website of the German Federal Archives.)1

When employed to drop shells on top of a target, the light Minenwerfer paled in comparison to Stokes mortar. At 53 kilograms, the latter weapon weighed much less than the light Minenwerfer. Moreover, it enjoyed a slight edge when it came to the amount of explosive contained in its projectile and a considerable advantage in the realm of range. (The last-named virtue owed much to the use of the Brandt-Maurice bomb.)

At the same time, while the accuracy of a Stokes mortar suffered when it was emplaced on ground that was either too hard or too yielding, the heavy platform of the light Minenwerfer provided it with a great deal of inherent stability. Thus, while the platform increased the weight of the light Minenwerfer, and added to the time needed to configure it in ‘mortar mode’, it also eliminated the need to improvise foundations.2

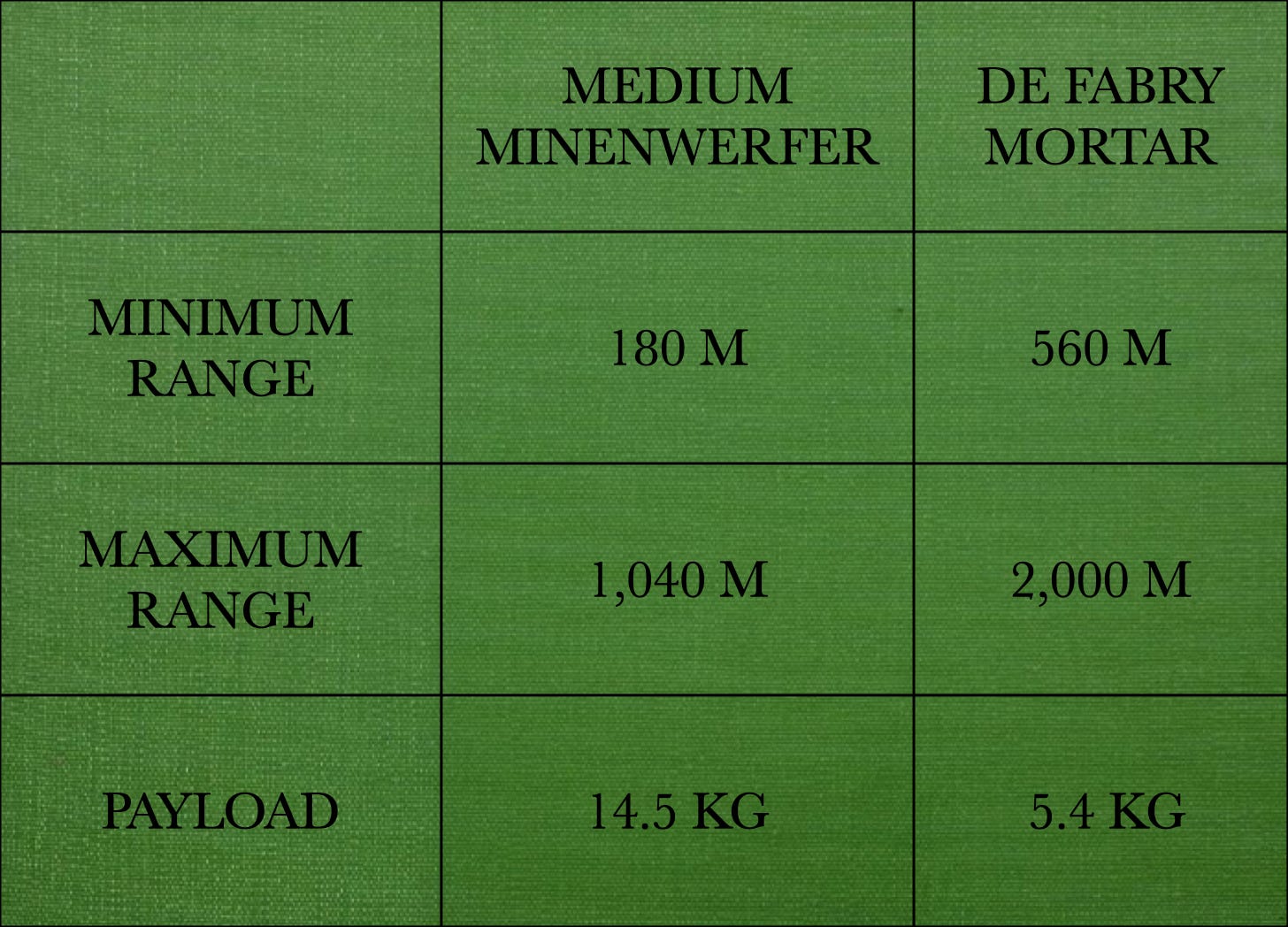

The medium Minenwerfer compared favorably to its closest foreign counterpart, the 150mm de Fabry mortar adopted by France in 1917. (As was the case with the Stokes, the ability of the de Fabry mortar to reach distant targets owed much to the combination of a smooth-bore tube and a finned projectile.)

Sources:

For Minenwerfer: H. Martin ‘Les Minenwerfer dans l’Armée Allemande’ [‘Trench Mortars in the German Army’] Revue d’Infanterie Volume 66 (1925) pages 423-435 (March) and 543-558 (The drawing of a light Minenwerfer used to create the illustrations for this post also come from this article.)

For the de Fabry Mortar: Lacuire and others at the École d’Application d’Artillerie [Artillery Basic School] Artillerie de Tranchée [Trench Artillery] (Metz: École d’Application d’Artillerie, 1935) pages 49-55

For the Stokes Mortar: R. Bouchon Cours d’Artillerie de Tranchée [Trench Artillery Course] (Bourges: Centre d’Instruction d’Artillerie de Tranchée, 1918) pages 39-40

For the Photo: US National Archives

For Further Reading:

To Share, Support, or Subscribe:

The German Federal Archives date these pictures to ‘1916 or so’. However, the uniforms worn by the soldiers in the photos makes it clear that they were taken between 1919 and 1933.

The classic type of improvised foundation for a Stokes mortar consisted of a shallow pit filled with sandbags. For a description of this technique, see US Army Basic Field Manual. Volume III, Basic Weapons. Part Four, Howitzer Company (Washington: Government Printing Office) page 65