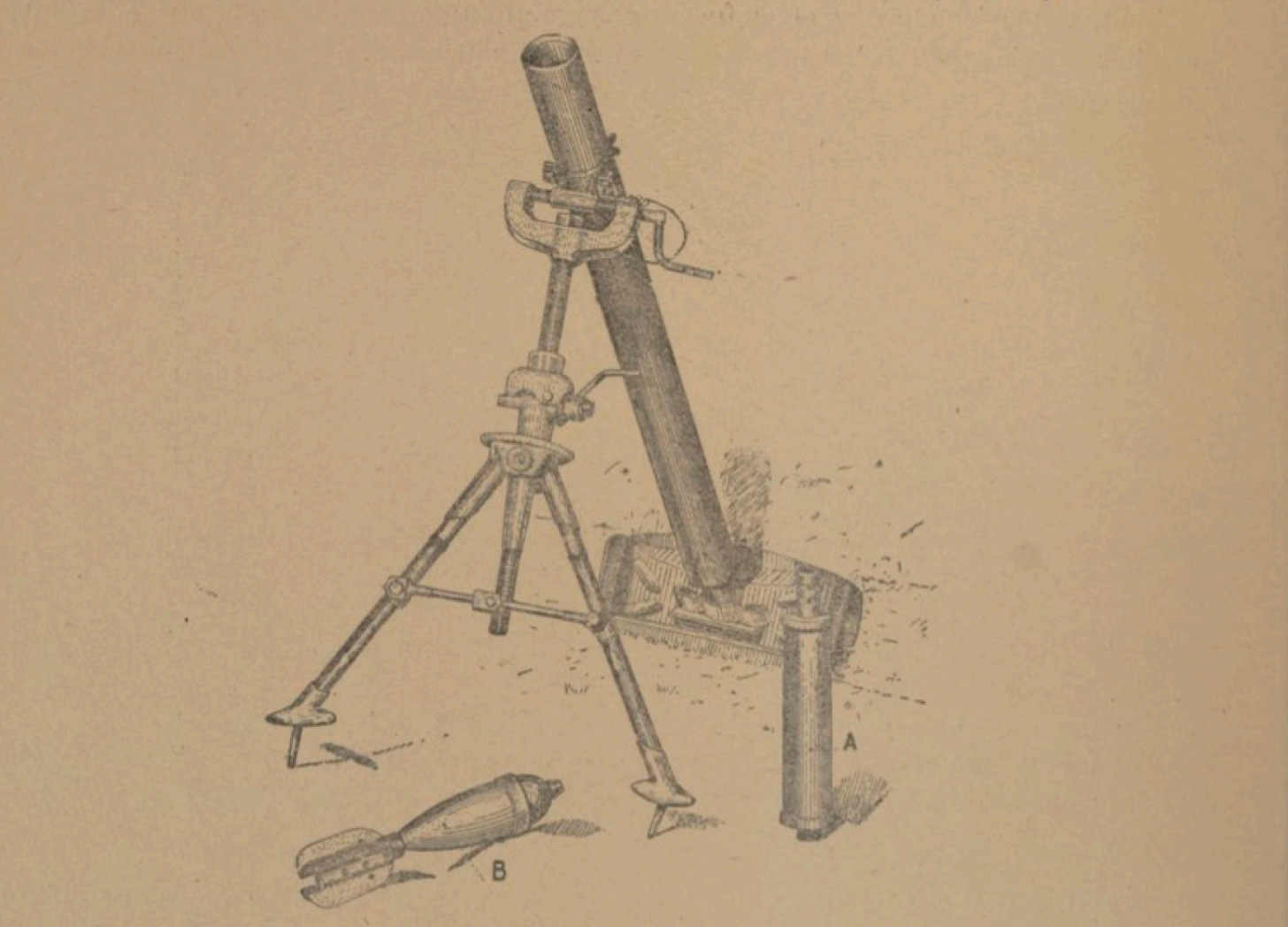

During the brief (but eventful) life of the American Expeditionary Forces, many soldiers of the United States became fond of two very different crew-served weapons: the 3-inch Stokes mortar and the 37mm infantry gun. The first of these, which had been in use in the British Army since 1915, was a drop-fired, muzzle-loading, smooth-bore weapon that dropped its bombs on top of their intended victims. The second, adopted by the French Army in 1916, was a breach-loaded rifle that, thanks to its relatively high velocity, fired its one-pound shells along a much flatter trajectory.

French and British soldiers dealt with the 37mm infantry gun and the 3-inch Stokes mortar as independent phenomena. At first, American soldiers imitated this custom. However, by the time that the Armistice of 11 November 1918 put an end to the fighting in France and Flanders, Americans rarely discussed one of the two weapons without mentioning the other. The two weapons thus became, like salt and pepper shakers, inseparable components of a matched set.

Soon after the Armistice, the General Headquarters of the American Expeditionary Force charged a board of officers with the creation of a comprehensive design for the post-war US Army. This board recommended that platoons armed with 37mm infantry guns and 3-inch mortars, which were then assigned to the headquarters companies of infantry regiments, be brought together to form “howitzer companies.”1

The curious name of these new type of unit may have had something to do with the occasional practice of describing “trench mortars” as “trench howitzers.” The main motivation, however, seems to be stemmed from the desire, laid out at length in the report of the board, for a weapon that would eventually replace both the 37mm gun and the 3-inch mortar. Failing that, the board proposed a project to develop a replacement for the 3-inch mortar that would enjoy advantages in such areas as range, accuracy, and the reliability with which projectiles exploded at the right place and time. (The shells fired by 3-inch inch mortars during the war acquired a reputation for failing to explode at the end of their flight and, what was worse, exploding before they began their journey.)

The report of the board made brief mention of 3-inch mortar projectiles that greatly increased the range of the weapon. These seem to have been the Brandt-Maurice projectiles that had recently been adopted by both the French and British armies.2 Unlike the earlier shells fired by 3-inch mortars, which might well be described as flat-topped cylinders, the Brandt-Maurice bombs were pear-shaped projectiles fitted with fins. Moreover, where the original 3-inch mortar shells used a time fuze, the Brandt-Maurice bombs exploded on contact with the ground.

Many at the General Headquarters of the American Expeditionary Force knew about the Brandt-Maurice projectiles. Indeed, in September of 1918, no less of a person than General John Jacob Pershing was so impressed by the new bombs that he ordered that, once sufficient stocks became available, they would make up three-quarters of the ammunition allowance for each 3-inch mortar.3 (The older shells, one presumes, would have been set aside for situations in which range could be sacrificed for a sake of greater destructive effect.)4

For Further Reading:

To Share, Support, or Subscribe:

Portions of the report of the board were reprinted in the Infantry Journal of June 1920 (pages 1029-1038) as Infantry Organization.

The British Army adopted the Brandt-Maurice projectile during the war. However, the projectile was not available for delivery to formations on the Western Front until after the Armistice had been signed. Ministry of Munitions, History of the Ministry of Munitions, Volume XI, The Supply of Munitions, Part I, Trench Warfare Supplies (London: HMSO, 1922) pages 67-68

Combat Instruction, dated 5 September 1918, reprinted in The United States Army in the World War, 1917-1921: Policy-forming Documents of the American Expeditionary Forces (Washington: Center for Military History, 1989), pages 491-495

In July of 1917, General Paul Maistre (1858-1922), then commanding the French Sixth Army, proposed the use of 3-inch Stokes mortars to create impenetrable barrages in front of French positions at the moment when the Minenwerfer projectiles stopped falling and the Stosstrupps began to move forward. Note relative aux attaques allemandes sur le front de la VIe Armée, dated 22 July 1917, reprinted in Les Armées Françaises dans la Grande Guerre, Tome V, 2ème Volume, Annexes, 2ème Volume, pages 249-251