The Artillery School in Berlin (I)

From the Memoirs of Major General Franz von Lenski (1865-1942)

Here at the Old Headquarters Building, the shelves groan under the weight of the memoirs of German general officers who served as such in the First World War. On the whole, the authors of these works tell us little about the lives they led in the years leading up to the conflict and less about their experience in the peacetime armies of Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, or Württemberg. For this reason, I took great pleasure in the discovery of a memoir, written by Franz von Lenski (1865-1942) in the 1920s, that recounts his adventures as a junior officer during the Belle Époque. Better yet, this autobiography provides detailed descriptions of the teaching methods used at two military schools for officers of the Prussian Army - the Unified Artillery and Engineer School and the War Academy.

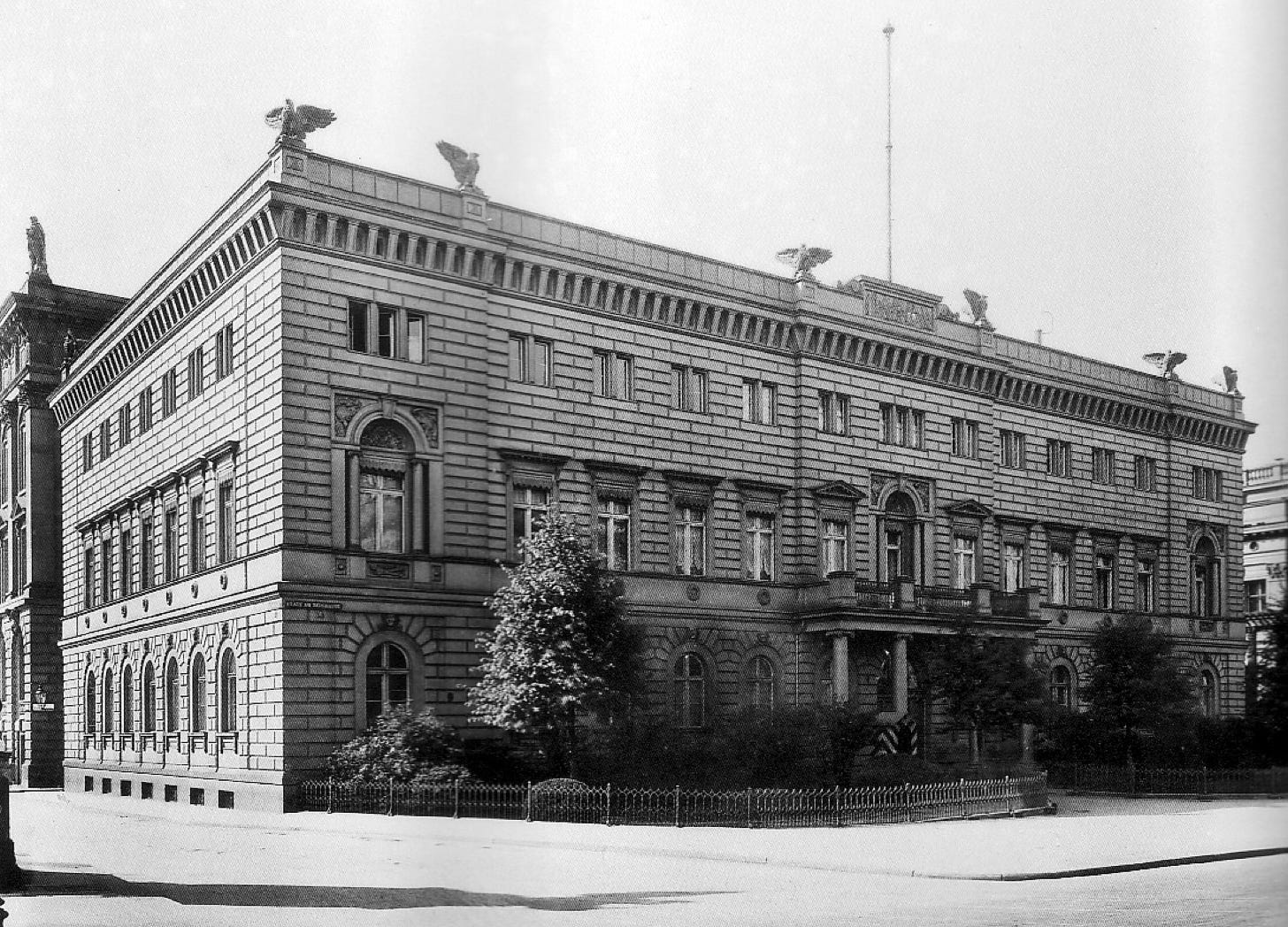

In the chapter that follows, Major General von Lenski describes the program of studies at the Unified Artillery and Engineer School, his impressions of Berlin in the 1880s, and such rarely discussed matters as the quarters occupied by junior officers and the life lived by his bâtman.

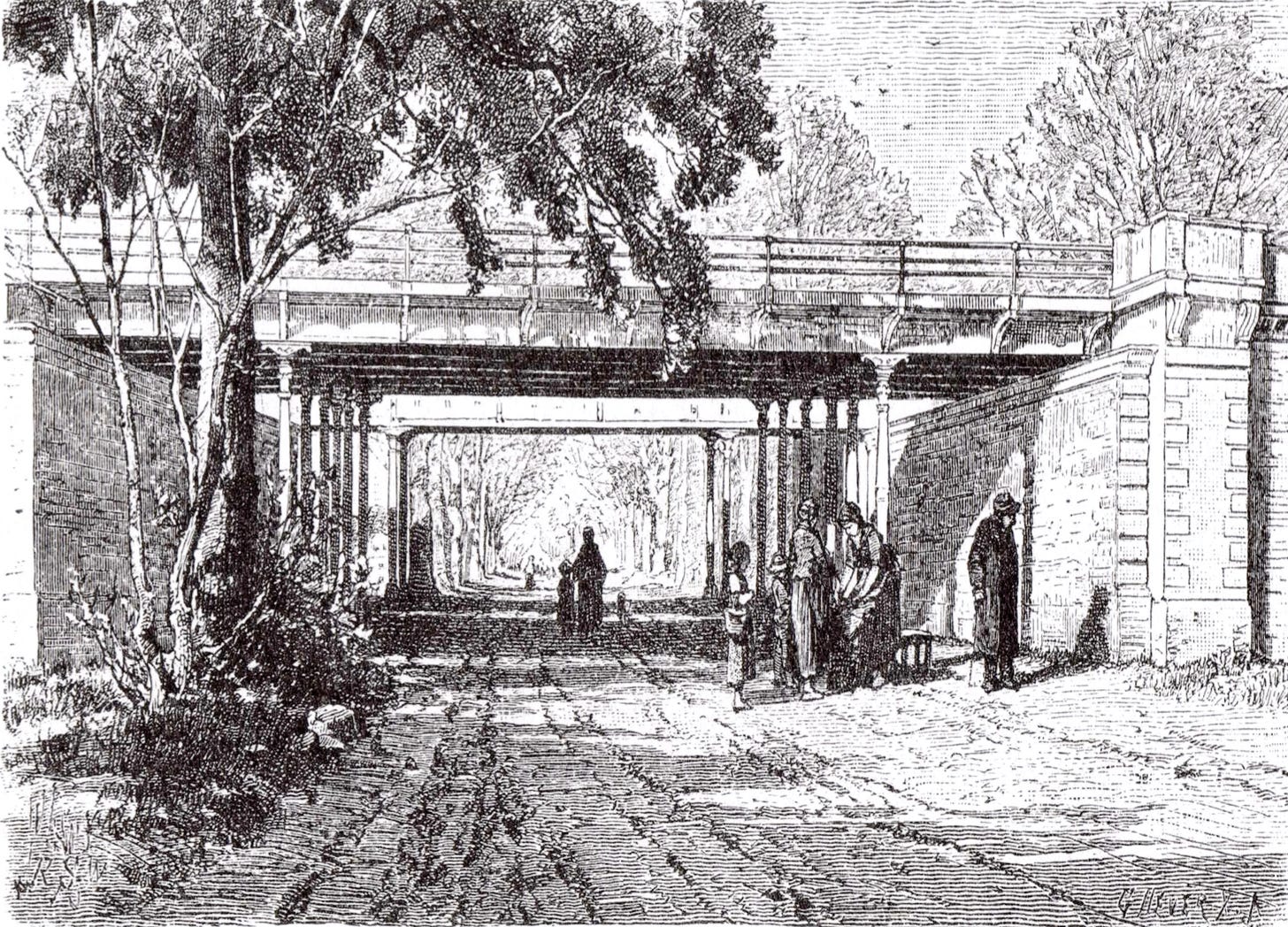

We lieutenants of the 23rd Field Artillery Regiment, a stately group of six and a second-year officer, who had been assigned to the so-called Selekta of the Artillery School, reported for duty in Berlin. On the morning of 28 September 1885, the latter met me, and some comrades who had traveled with me, at the railway station on Friedrich-Strasse. The City Train was somewhat new to me. During my years at the cadet school at Gross-Lichterfeld (1879-1883), I had only seen it under construction. Apart from this, I don’t think much in the way of development took place in the two years that had I spent away from Berlin. On the contrary, I view the whole decade of the 1880s as a period of relative stagnation. (The enormous expansion of the city, which the world watched with amazement, did not begin until 1890 or so.)

As a rule, courses at year-long schools for military officers usually began on 1 October. However, thanks to a local peculiarity, course at the Artillery School started on 29 September. The next day, you see, was the birthday of the elder Empress Augusta, in celebration of which all soldiers walking on the streets of Berlin were obliged to wear their helmets.1 As it would have been impossible to communicate this order to young officers and their batmen arriving in Berlin on that day (so as to be able to report for duty on 1 October), the presence of so many soldiers ‘out of uniform’ would have resulted in many unpleasant reprimands and inquiries from the Office of the Commandant.2 So, the first day of the course was moved to 29 September, so that those who reported for duty could be commanded to wear helmets on the following day.

This practice persisted for many years. Indeed, it remained in force long after the old empress had died and the Artillery School had been transformed into the Military-Technical Academy. Students continued to report on 29 September until, one day, a resourceful adjutant, who had taken the trouble to search through some old files, discovered the reason for this anomaly. This episode reminds me of the story of the sentry that Catherine the Great once posted to protect a rare flower that grew in the Peterhof park in Saint Petersburg, and how, more than a century later, a soldier could still be found standing at that spot, even though no one knew the reason why.

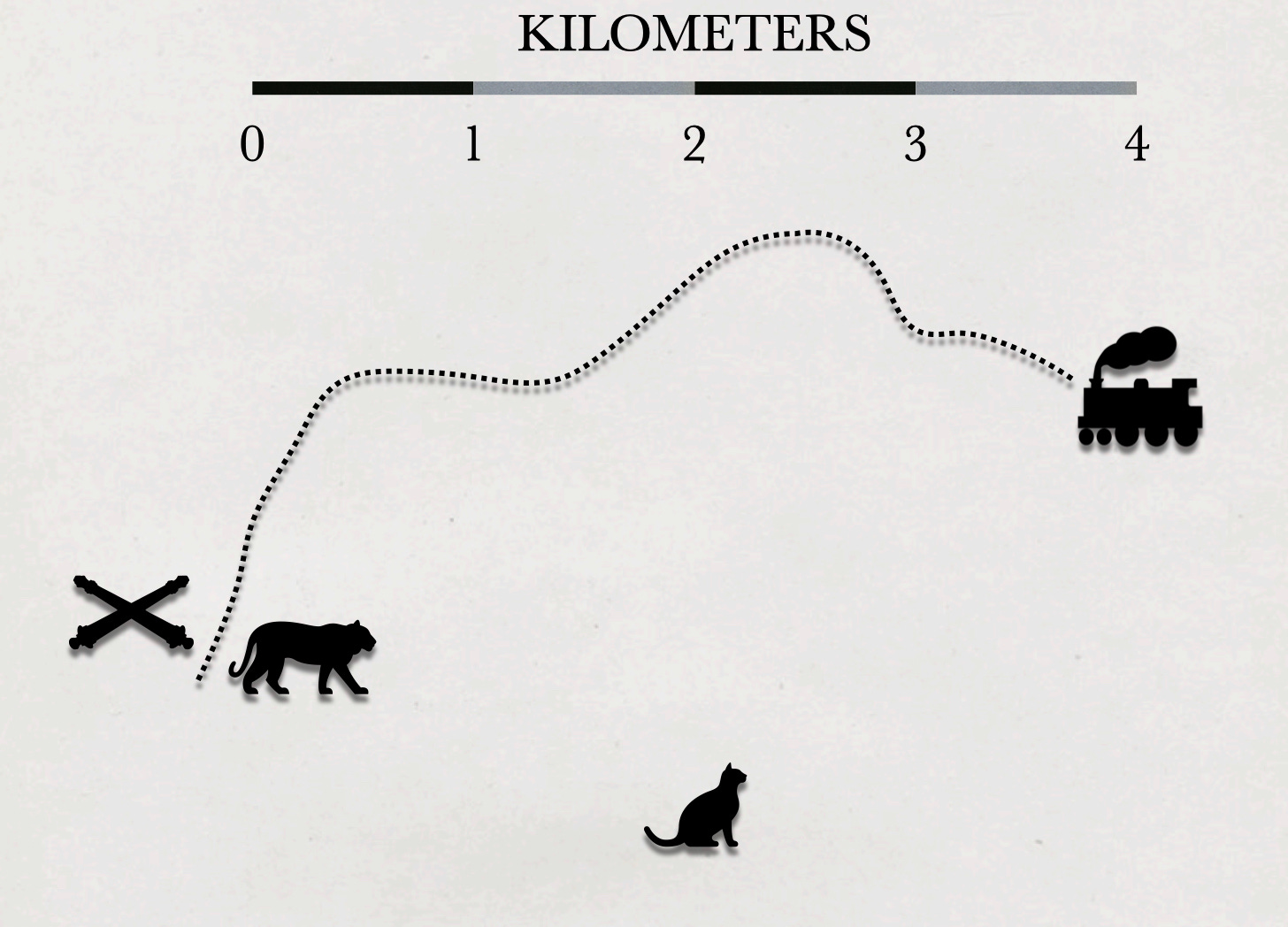

The first thing that I needed to do was find an apartment. I considered only two neighborhoods of the city: the vicinity of Karl-Strasse, Schumann-Strasse, Marien-Strasse, and Louisen-Strasse, from which I could take the City Train to the station at the Zoological Garden, which was close to the Artillery School, and the West (now called The Old West), around Potsdammer Strasse and its cross streets. (From there, we would be able to get to our educational institution on foot, or in a horse-drawn trolly.)3

All of the officers from the 23rd Field Artillery Regiment chose to live in the West, a decision which we never regretted. The other neighborhood we looked into, the so-called Latin Quarter, was decidedly dirtier and more richly supplied with bugs.

With little difficulty, I found an apartment at Körner-Strasse 17, up a flight of stairs, above a butcher's shop. I hardly ever saw the landlord, who was Polish. His wife was a typical dyed-in-the-wool Berlin landlady, friendly when she wanted something, but otherwise inclined to scratch.4

The apartment, which held an ordinary bed, a roll-top writing desk, a chest-of-drawers, an old wardrobe, a carpet from a flea market, and a wall clock that never worked, was typical. My batman lived in a small room behind the kitchen. It cost me 36 marks a month, without breakfast, which I had to organize for myself. If the apartment had been a little more elegant, it might have cost me as much as 45 marks. A two-room furnished apartment cost 60 to 75 marks. If we factor in inflation, which has reduced the purchasing power of a mark to that of a penny of those days, the prices paid for housing in that neighborhood has not really changed. I need not say that the people who lived in those apartments were completely uninhibited in every respect.

To be continued …

Source: Franz von Lenski Aus den Leutnantsjahren eines alten Generalstabsoffiziers [From the Years an Old General Staff Officer Spent as a Lieutenant] (Berlin: Georg Bath, 1922) Chapter 4 ‘Die Vereinigte Artillerie- und Ingenieurschule zu Berlin’ [‘The United Artillery and Engineer School at Berlin’]

For further reading:

Links to all of the posts in this series can be found below:

To share, support, or subscribe:

Augusta of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (1811-1890) was the wife of Kaiser Wilhelm I (1897-1888). I presume that Lenski refers to her as ‘the elder Empress’ in order to avoid confusion with Augusta Victoria of Schleswig Holstein (1858-1921), the wife of Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859-1941).

In the armies of the German Empire, a ‘commandant’ [Kommandant] was an officer responsible for the good order and discipline for all of the soldiers serving in a particularly location. The Office of the Commandant [Kommandantur] therefore handled reports concerning the misbehavior of military men.

The first of these neighborhoods offered easy access to the Friedrich-Strasse station on the City Train line. The second could be found about three kilometers to the west of the Artillery School.

Lenski used the word Katzenfreundlich [‘friendly like a cat’] to describe the amicable aspect of his landlady’s personality.

What a great find. Please do translate the rest!

That is a great find. Memoirs that talk about the day-to-day life of people in the past are rarities and they are very valuable. People who write their memoirs think that the big events they participated in are what the readers will want to know about. But overtime the big events become the only thing anyone knows about, and we don’t need dozens or hundreds of similar stories about the big picture.. It’s the small details of day to day life that are completely lost, and that we people now living in the future. Want to know about.

While it’s not a military book. My favorite book in this category is Molly Hughes’s trilogy about growing up in London in the late 19th century.