The Artillery School in Berlin (V)

From the Memoirs of Major General Franz von Lenski (1865-1942)

Soon after the end of the First World War, Franz von Lenski (1865-1942) wrote a memoir of his adventures as a junior officer in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. The post the follows continues our serialization of the fourth chapter of this book, the one that deals with the year that Major General Lenski spent as a student at the United Artillery and Engineer School in Berlin. (The links listed at the bottom of this page, in the section marked ‘for further reading’, will take you to other posts in this series.)

As a rule, our classes began at 9 a.m. and ended at 2 pm, at which point all of the students (of whom there were more than 200), enjoyed, for a modest price, a good lunch in the main dining room. Afterwards they became free men, unreachable in the great city of Berlin. (This was a delicious feeling for young lieutenants, who, when serving with their regiments had been obliged to work from dawn to dusk.)

At meals, the officers of a given field artillery brigade sat together. On birthdays and other special occasions, the brigade threw a party, with bouquets of flowers in front of each place-setting and, for a fantastically low price, a mighty punchbowl filled with a mixture of porter (or ale) and sparkling wine. I won’t deny that sometimes the young officers (other than myself, of course) drank a little too much.

We had little homework to do. Nonetheless, every day, my bâtman carried my books and notebooks from [my apartment on] Körner-Strasse to the Artillery School and back again. This had less to do with my need to study, than my desire to occupy the time of my servant, who would otherwise have nothing else to do except keep my kit in good order.

This reminds me of a problem that arose as a result of the posting of so many young unmounted officers to Berlin, that of bâtmen.

Each student brought his own bâtman [who had taken care of him in his regiment]. As the latter had nothing more to do than look after his officer, attend a few roll calls, and do a bit of drill and ceremony, he rarely dealt with any other superior. I will not hesitate to describe this situation, not merely as nonsense, but as nonsense on stilts. Indeed, both the War Ministry and the Military Cabinet deserve serious reproach for failing to take forceful action to remedy this problem. The financial authorities of the armies were also aware of this travesty, but, for decades, did nothing more than talk about it.1

I was, I am sure, not the only young officer who realized that he was responsible for both educating and supervising the bâtman entrusted to him. At the same time, I am also certain that many less scrupulous lieutenants failed to take this duty seriously, thereby allowing many a young soldier to acquire habits that ruined him for life.

Later, when I attended the War Academy, a bâtman I fired left me with 50 marks worth of small debts that he had run up on my account. (I accepted the discomfort caused by this obligation as a well-deserved punishment for my temporary inattention.)

A bâtman saw all sorts of things in his officer’s bachelor household. A lieutenant attending our course shared his modest quarters with a woman not-his-wife for several months.2 That was certainly an exception to the general rule. Still, one should not overestimate the morals of ordinary people in this respect. They are not worse than ours, but they are different. That is, they see natural things as natural.

Nonetheless, bâtmen saw many things that they should not have seen, and, as a result, the authority of their superiors, which was otherwise so carefully maintained, suffered damage, thereby providing ammunition to the Social Democrats.

My own bâtman was, by the way, the very model of respectability. He never went out in the evenings, but sat at home, making things and carving pieces of wood. His name was Jakob Sturm, and he was a farmer’s son from Ostheim in Alsace.

I often found him reading a hymn book or the Bible, which led me to think that he was a member of a free church.3 At Christmas, he made me a box for letters, beautifully carved from pieces of wood taken from cigar boxes. (I use it to this very day.) I will always remember his kind, faithful face when he asked me to accept a bottle of Alsatian wine from his father’s vineyard. Alas, few bâtmen were like this tall, clumsy man with his gentle boyish face and clear blue eyes.

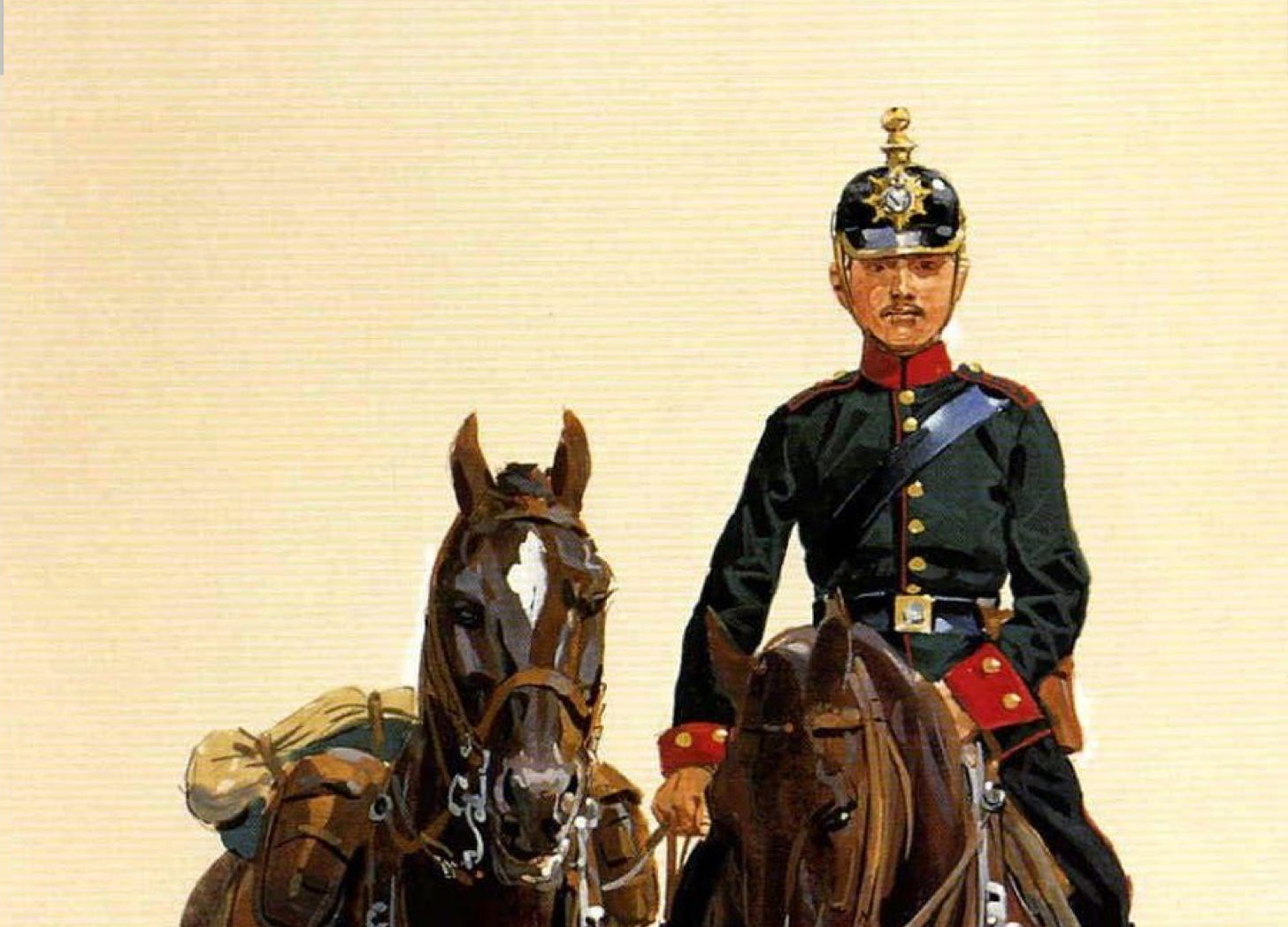

For the average soldiers, serving as a bâtman to a young, unmarried lieutenant in Berlin offered few benefits. The situation was, of course, different for a groom in the service of a cavalry officer posted to the capital. After all, someone with two or more horses to look after rarely lacks for work to do. Likewise, the what I have written did not apply to the households of married lieutenants.

To be continued …

Source: Franz von Lenski Aus den Leutnantsjahren eines alten Generalstabsoffiziers [From the Years an Old General Staff Officer Spent as a Lieutenant] (Berlin: Georg Bath, 1922) Chapter 4 ‘Die Vereinigte Artillerie- und Ingenieurschule zu Berlin’ [‘The United Artillery and Engineer School at Berlin’]

Links to all of the posts in this series can be found below:

To share, support, or subscribe:

I used the phrase ‘financial authorities of the armies’ to translate Militärbehörden.

Lenski used the French phrase faux ménage (‘false housekeeping’) to describe this situation.

I used the term ‘member of a free church’ to translate Sektierer, which referred to a person belonging to a Protestant denomination other than the established church of a given state of the German Empire.

Thanks very much for your writings. I greatly appreciate the time and effort that you must put into making the obscure yet fascinating diaries such as this one available to your readers.