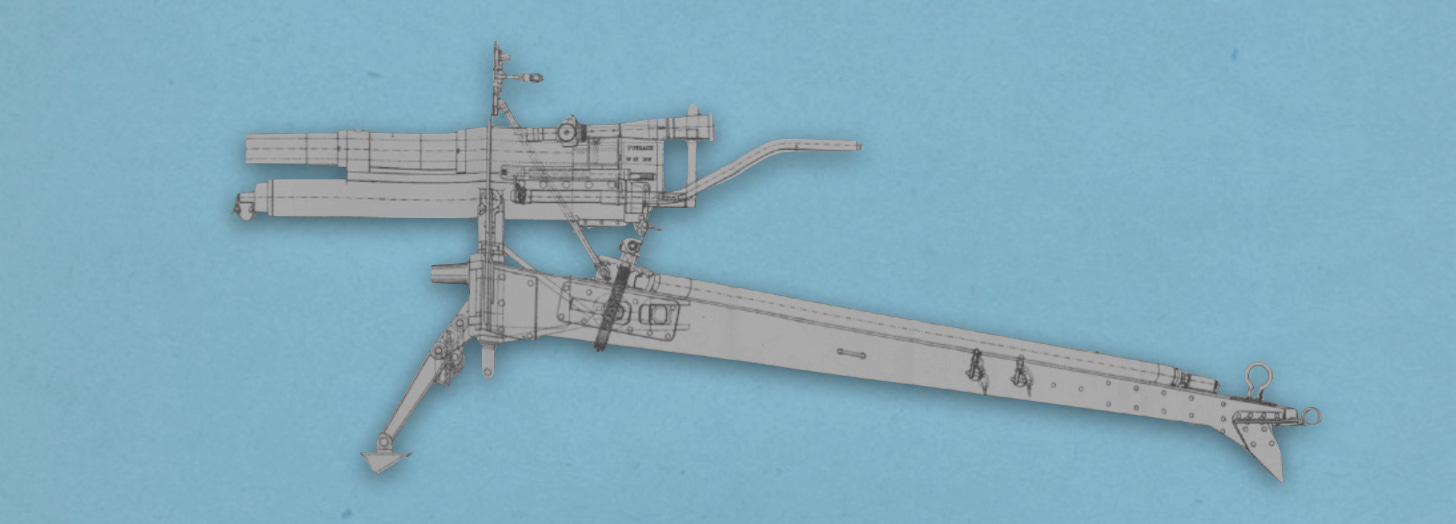

In 1885, the French Navy adopted a 37mm gun designed by the armaments firm of Hotchkiss and Company. Placed on a pedestal mount, this piece provided torpedo boats with a means of firing shells at small craft and canister rounds at hostile boarding parties.1

At the outbreak of the First World War, some of the canons de 37 (modèle 1885) ended up on the improvised armored fighting vehicles that flourished in the short summer of mobile warfare. A few weeks later, when summer gave way to autumn, and position warfare took the place of grand maneuvers, French naval arsenals mounted a number of these guns on improvised carriages, fitted the carriages with shields, and sent them to the front.

The authorities who sponsored this migration imagined that the 37mm guns would fire canister rounds against German soldiers on the verge of jumping into French trenches. Soon, however, French soldiers at the front discovered that the 37mm guns sent forward to serve as ‘flanking pieces’ could do other things as well.

On Christmas Day of 1914, Joseph Joffre, generalissimo of French forces on the Western Front, signed a circular letter that, among other things, described the abilities of the 37mm guns provided by the Navy.2

Out to distances of five hundred meters, the 37mm naval gun can destroy machine guns and tear up the parapets of trenches fitted with shields. Their projectiles piece the sheet metal of German shields. Their shrapnel shells are very effective against personnel. They are very accurate.

The infantry finds it easy to understand these weapons because their fire resembles that of machine guns.

The 37mm gun has no effect upon barbed wire obstacles.

As soon as possible, 37mm guns with shields should be distributed to armies in the field.Over the course of the year that followed, French soldiers at the front found the repurposed naval pieces to be at once, useful, unwieldy, and scarce. To solve the latter two problems, the French War Ministry instructed the state arsenal at Puteaux to design a weapon that, while firing the same ammunition as the existing 37mm gun and mimicking its ballistics, would be easier to both move and hide. In December of 1915, it approved the prototype that resulted from this effort and asked the arsenal to produce 1,300 copies.

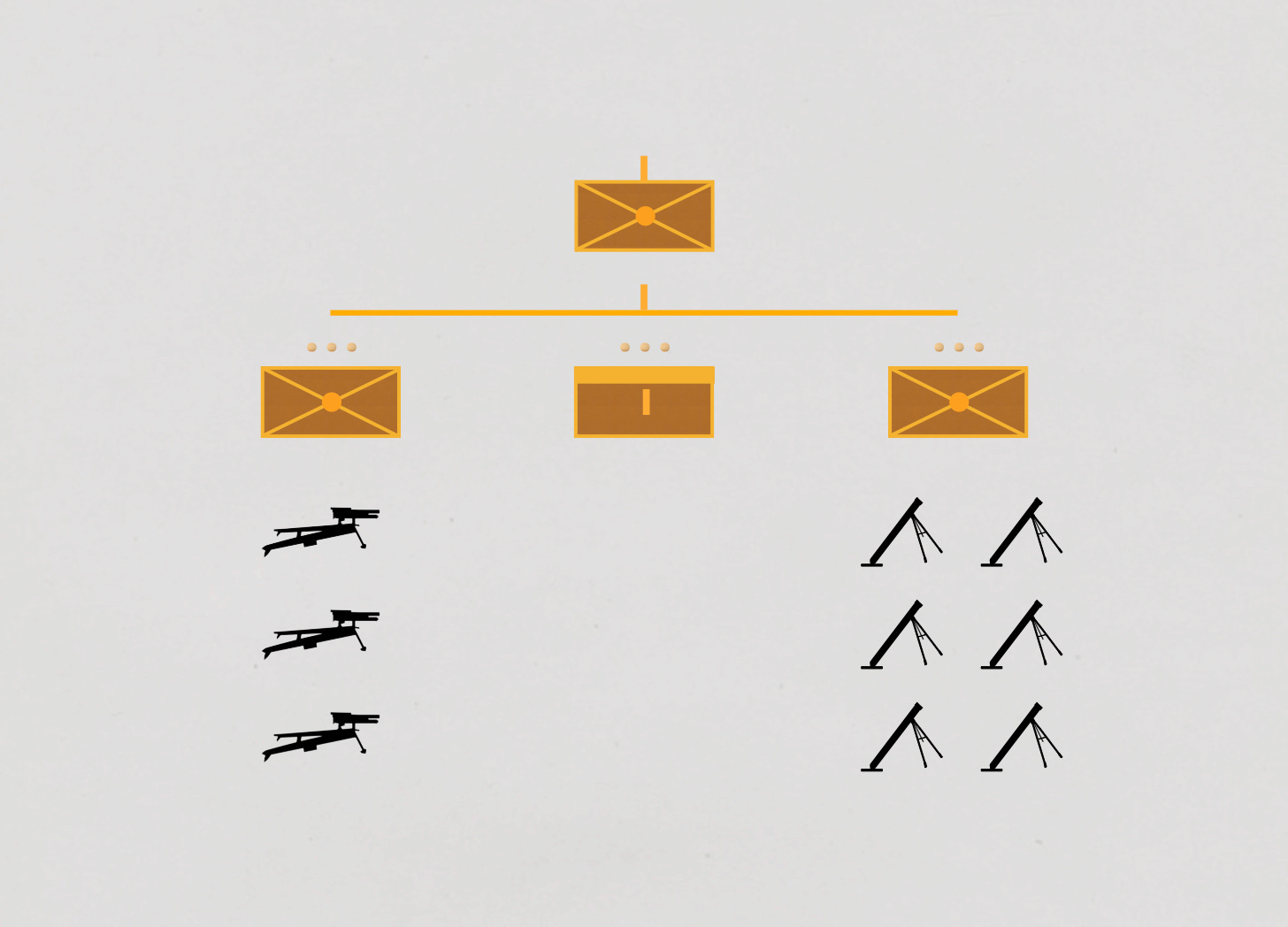

In the course of 1916, the workshops at Puteaux produced one of the new 37mm guns for each of the more than nine hundred infantry battalions serving at the front. Thus, by the end of that year, most French infantry regiments (each of which usually consisted of three battalions) were able to equip a platoon with three weapons of that type. (In combat, the commander of the platoon, which belonged to the regimental headquarters company, reported directly to the commanding officer of the regiment.)

The following summer, the French Sixth Army took delivery of two hundred infantry mortars. These allowed each infantry regiment in that formation to form a unit armed with six such weapons. In the year that followed, the infantry regiments of other French field armies received enough weapons of that class to form comparable platoons of their own. (Some of the weapons used to arm these units were 75mm Jouhandeau-Deslandres mortars made in France. Most, however, were Stokes 3-inch mortars that had been provided by the United Kingdom.)3

The provision of two types of ‘accompanying engines’ [engins d’accompagnement] to each infantry regiment raised the question of their location in the organizational framework of such units. Officially, the platoons armed with such weapons belonged to the regimental headquarters company [compagnie hors rang]. Occasional mention of a company or half-company [peleton] of ‘engines’ or ‘accompanying engines’ suggests that some regimental commanders placed both their heavy weapons platoons under a single commander.4

Soon after the end of the war, the peacetime French Army adopted the practice of replacing two single-weapon platoons with three mixed platoons [sections mixtes], each of which added one 37mm gun and two mortars to the arsenal of an infantry battalion. (In an article that he wrote for the original Tactical Notebook, John Sayen argued that the practice of assigning mixed platoons to infantry battalions began during the war.)5

By 1927, French infantry regiments of the type optimized to fight in the northeast of Metropolitan France had replaced the three mixed platoons with a single regimental weapons company [compagnie d’engins]. Consisting of a platoon of three 37mm guns, a platoon of six mortars, and a headquarters platoon [section de commandement], this allowed the regimental commander to distribute his heavy weapons as he saw fit.6

For Further Reading:

Jean-Jacques Monsuez ‘Artillerie de marine HOTCHKISS : un fleuron français à la fin du XIXe siècle’ [Hotchkiss Naval Artillery: A French Flourish at the end of the Nineteenth Century] Revue Historique des Armées 2003 pages 107-125

Note relative aux divers engins de destruction contre le personnel et le matériel [‘Note About the Use of Various Destructive Devices Against Personnel and Matériel’] reprinted in the French official history (Les Armées Françaises dans la Grande Guerre [French Armies in the World War]) as Annexe Numéro 460, Tome II, Annexes 1er Volume page 657

For the request for Stokes mortars made by the commanding general of the Sixth Army, see ‘le général de division Maistre, commandant la VIe Armée, à Monsieur le général commandant en chef’ reprinted in the French Official History as Annexe Numéro 810, Tome V, 2e Volume, Annexes, 2e Volume pages 295-296

For examples, see Alphonse Grasset La guerre en action. Le 8 août 1918 à la 42e division : Montdidier [War in Action, Number 5. The 42nd Division on 8 August 1918: Montdidier] (Paris: Berger-Levrault, 1930) pages 57 and 194 and Journal Officiel de la République Française [Official Journal of the French Republic] (December 1920) page 20297

John Sayen ‘French Infantry After August 1914 (Part II: 1917 and 1918)’ The Tactical Notebook (July 1992)

École Militaire d’Infanterie et des Chars de Combat [Military School for Infantry and Tanks] Cours d’Emploi des Armes [Course on the Use of Weapons] (Saint-Maixent-l’École: Litho de l’École Militaire, 1933) Volume 1, pages 20-21

Posts like this are the real reason I got on Substack

Thanks for this interesting article.

I haven’t read of a similar weapon being used by the British forces in WW1, nor of these guns in use by any army during WW2.