In the autumn of 1914, as so many of those serving on the Western Front dug trenches and strung wire, the godfathers of the armored fighting machines so recently improvised by French soldiers and sailors prepared for the return of open warfare. In the realm of matériel, these efforts included the replacement of all armed, but poorly armored, vehicles with trucks protected by plates of tempered steel. In the dominion of structure, the relevant authorities turned ad hoc collections of men and ordnance into units of standard types. Thus, the automotive adventurers who had survived the summer of 1914 formed themselves serving in company-sized groupes, each of which employed both vehicles armed with machine guns (autos-mitrailleuses) and trucks (autos-canon) that sported light cannon.

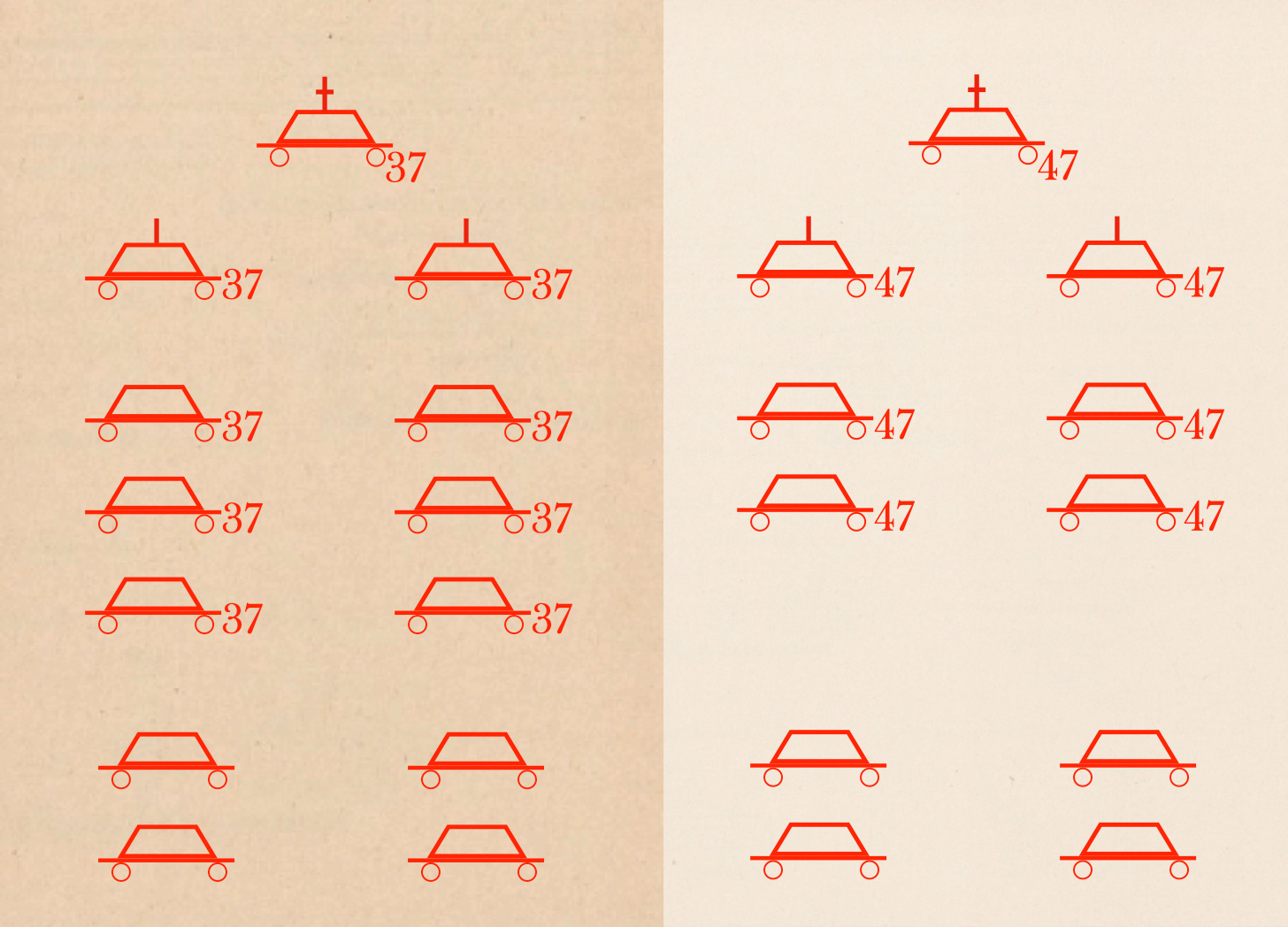

The most common type of groupe, sixteen of which were formed before Christmas of 1914, possessed six trucks armed with 37mm cannon, four trucks armed with machineguns, two unarmed liaison cars, and two cargo trucks. These units kept company with a smaller number of groupes in which the sharp end consisted of four autos-cannons equipped with 47mm guns and four autos-mitrailleuses.

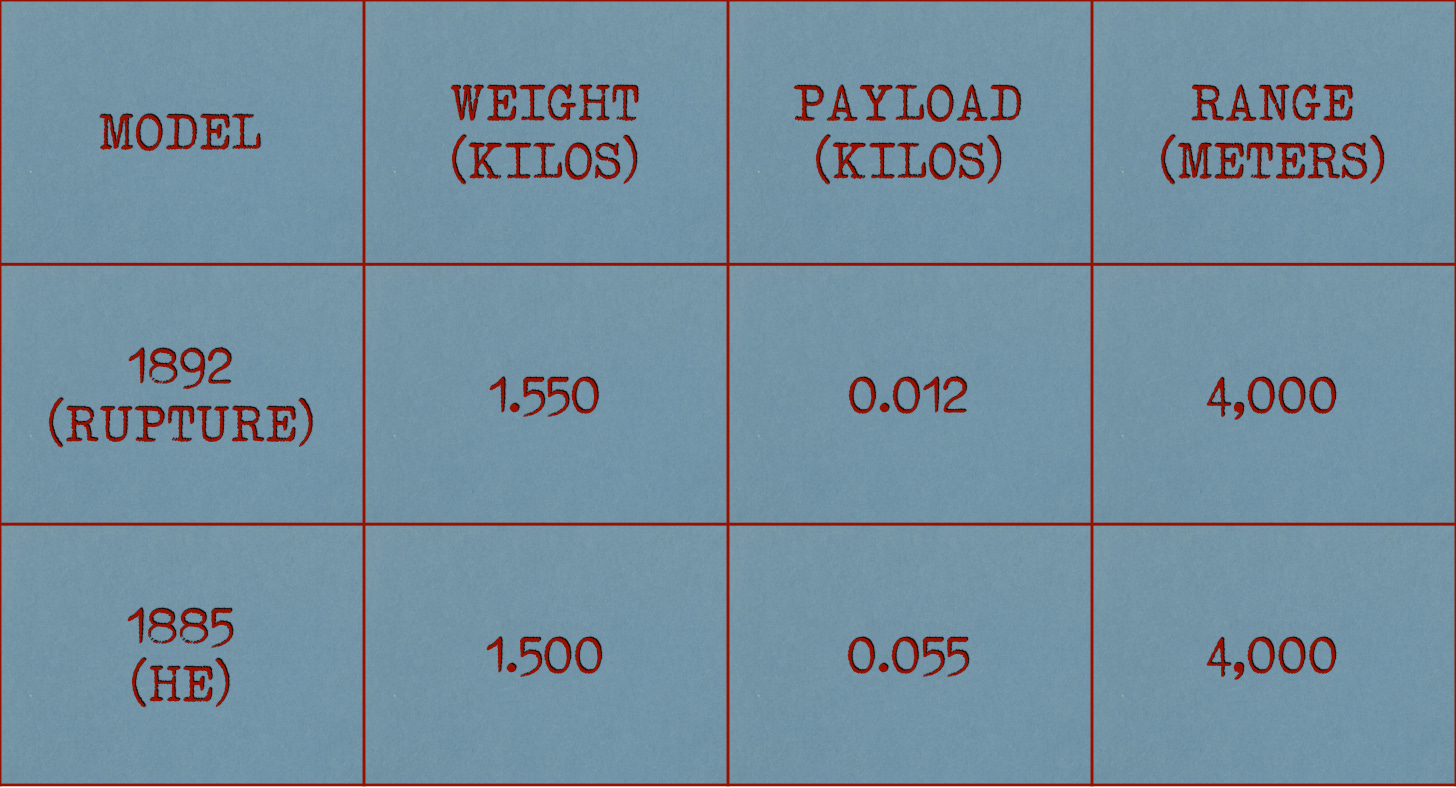

The cannon carried were of types developed by the Navy for use on torpedo boats and other vessels of modest size. (This connection led to the light-hearted designation of the auto-canon as a ‘torpedo boat on wheels’.) The 37mm guns, of models introduced in 1885 and 1902, fired half-kilogram (one-pound) projectiles. The 47mm gun, standardized in 1885, fired shells that weighed three times as much.

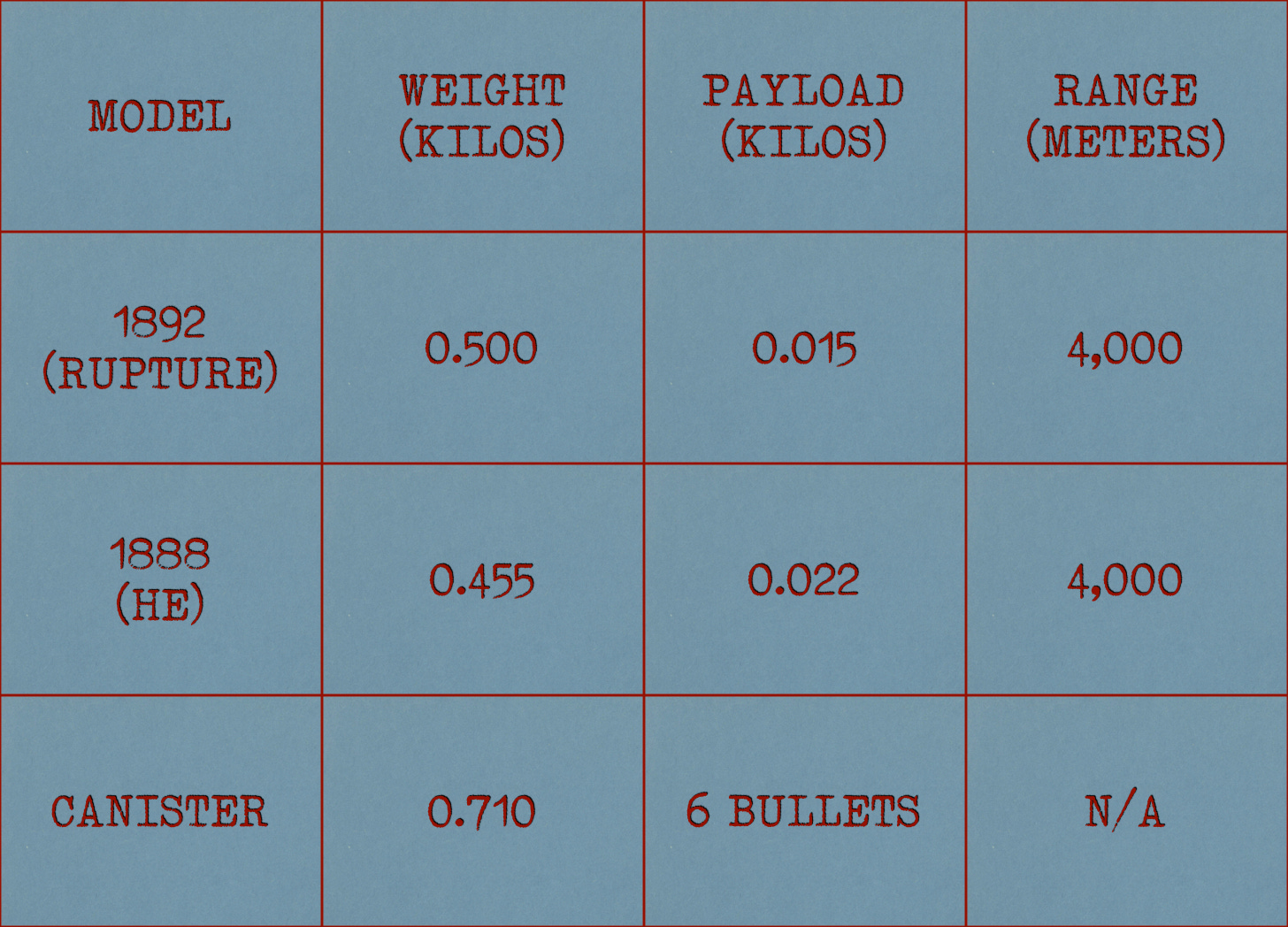

The shells provided with the light naval cannon were of two basic types: armored-piercing (known as obus de rupture) and high-explosive (known simply as obus). The 37mm gun also fired canister (boite de mitraille) rounds, each of which delivered, at ranges too short to quantify, six musket balls and forty-three fragments.

At first, the armored vehicle units bore designations that reminded all concerned of the caliber of the ordnance carried by their autos-canons. Thus, the units equipped with 37mm guns became known as groupes d’autos-canons de 37 and those armed with 47mm pieces were called groupes d’autos-canons de 47. (This nomenclature betrays the presumption that, while the business end of each group consisted of gun trucks, the vehicles fitted with machine guns served chiefly as escorts.)

Both types of units employed binary frameworks. Thus each groupe consisted of two platoons, each of which possessed five or six vehicles: two or three armed with cannon and two with machine guns. As a rule, the officer commanding a platoon took direct charge of the cannon-armed vehicles, leaving the leading of the two machine gun vehicles to his ‘machine gun officer’ [officier mitrailleur].

The naval officer commanding a groupe, which corresponded to a company, battery, or squadron of the French Army, usually wore the cuff stripes of a full lieutenant (lieutenant de vaisseau). He enjoyed the services of three other officers, an ensign [enseigne de vaisseau] and two machine-gun officers. (The latter ranked either as junior ensigns or senior midshipmen.)

In action, the lieutenant commanding led one of the two platoons and the ensign the other. Within each platoon, while the senior officer took direct charge of the gun trucks, the officiers mitrailleurs supervised the service of the vehicles fitted with machine guns.

The availability of naval personnel for service in armored car units owed much the way that the French Navy obtained the lion’s share of its junior personnel. In peacetime, most rank-and-file sailors, and a goodly proportion of junior naval officers, spent but two or three years in uniform before passing into the reserve. Thus, when war broke out in 1914, the depots of the Ministry of the Marine possessed far more officers and men than were needed to man its ships and installations ashore.

This organizational accident proved fortuitous. While relatively few Frenchmen of 1914 had much experience with motor vehicles, French sailors had been dealing with fuel-burning machines for three generations. Moreover, some of them had experience with the crew-served weapons, whether machine guns or small-caliber cannon, fitted to small craft of various kinds.

In the course of the first eighteen months of the First World War, the reservoir of reservists enjoyed by the French Navy began to dry up. Thus, in February of 1916, the Ministry of the Marine asked the Ministry for the return of the men who had been serving with armored car units. At first, military authorities drew the replacements for the sailors lost by this transfer from the training and replacement organization of the 13th Field Artillery Regiment. However, as this depot had also been charged with the supply of trained officers and men to a growing number of batteries, the military authorities assigned responsibility for the care and feeding of armored car units to the cavalry.

Sources

Alain Gougaud L’Aube de la Gloire, Les Autos-Mitrailleuses et les Chars Français Pendant la Grande Guerre [Dawn of Glory: French Armored Cars and Tanks during the Great War] (Issy les Moulineaux: Société OCEBUR, circa 1987) pages 61-64

Dominique Waquet Groupes Autos Mitrailleuses Autos Canons 1914 1918: Textes Fondateurs (Suresnes: Casseul et Rougeret, 2022) pages 4 and 5

Ministère de l’Armament et des Fabrications de Guerre Renseignements sur les Matériels de Tous Calibres en Service sur les Champs de Bataille des Armées Françaises [Information about Artillery Pieces of all Calibers Employed on the Battlefields of French Armies] (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1918) pages 18 and 46

For Further Reading:

And thus was born the motorized (later mechanized) cavalry? Funny how history works. I wonder what the effect would have been if the groupes had accompanying units of dismounts composed of Fusiliers Marins or Troupes Coloniales (Troupes de Marine)?

Change is constant. I thought it was interesting that all the ranges were 4,000 meters