Between 1923 and 1925, Lieutenant Colonel Abel Clément-Grandcourt (1873-1948) wrote a series of articles for the Révue d’Infanterie that proposed, among other things, changes to the structure of the infantry battalions of the French forces stationed in the Mandate of Syria. These reforms, he argued, would improve the ability of these units, which were drawn from many different parts of the French Empire, to fight in conditions that, while more conventional than those he had faced in North Africa, were less “European” than those he had experienced on the Western Front.

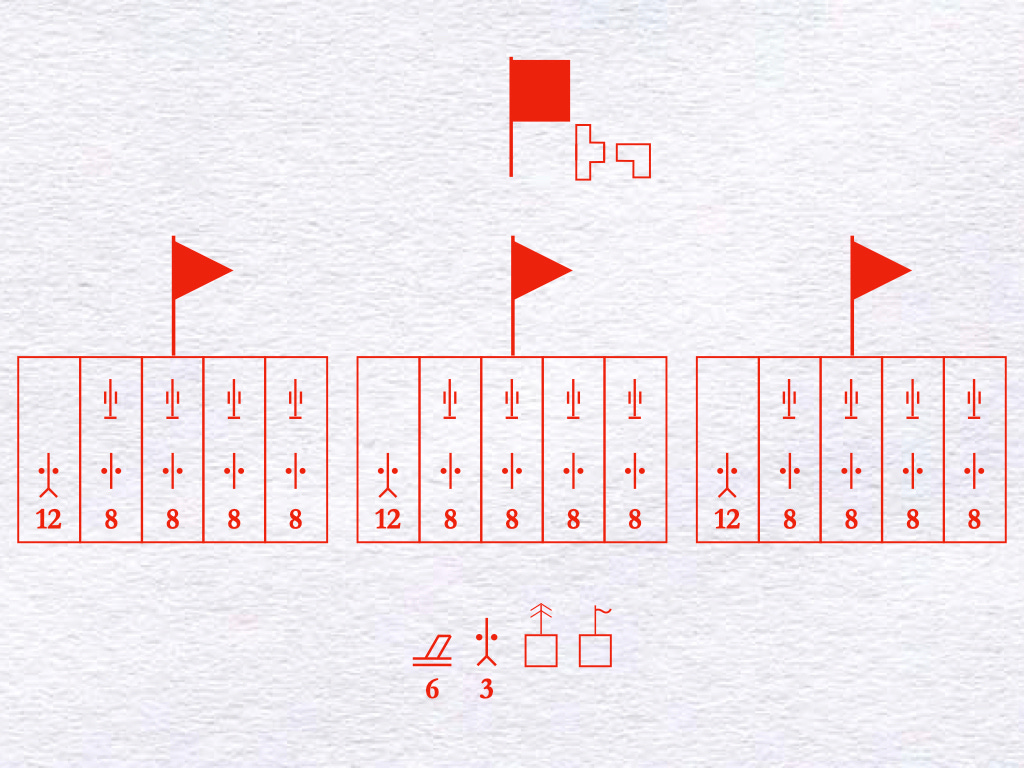

Where existing French infantry battalions possessed three rifle companies, Clément-Grandcourt argued that a battalion operating in Syria ought to have four such units. This, he explained, was less a matter of size than of tactical flexibility. Thus, while he preferred larger companies to smaller ones, he was willing to reduce the number of men in each rifle company in order to provide battalions with four such units.

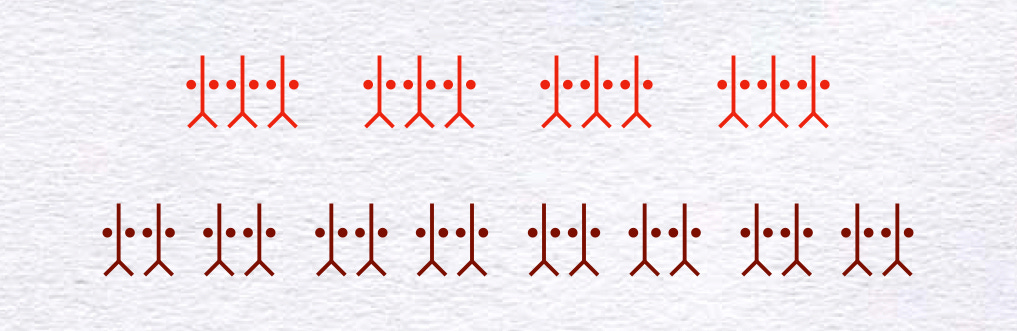

The component platoons of the four rifle companies of the battalion proposed by Clément-Grandcourt resembled those of the contemporary German Army. That is, each consisted of two rifle squads and two light machine gun squads. However, while the standard light machine gun of the Reichswehr was a belt-fed, water-cooled weapon that was only “light” when compared to a full grown Maxim gun, the automatic weapon of choice for Clément-Grandcourt was the Madsen light machine gun.

Clément-Grandcourt provided each of his ideal rifle companies with a single crew-served weapon, a modified 37mm gun of the model named for the arsenal at Puteaux. The existing version of this weapon, which had been optimized for shooting at the embrasures of machine gun positions, was poorly suited to the task of tracking fleeting targets. To overcome this handicap, Clément-Grandcourt recommended the fitting of a shoulder stock similar to the ones grafted to small-caliber cannon installed on naval vessels.

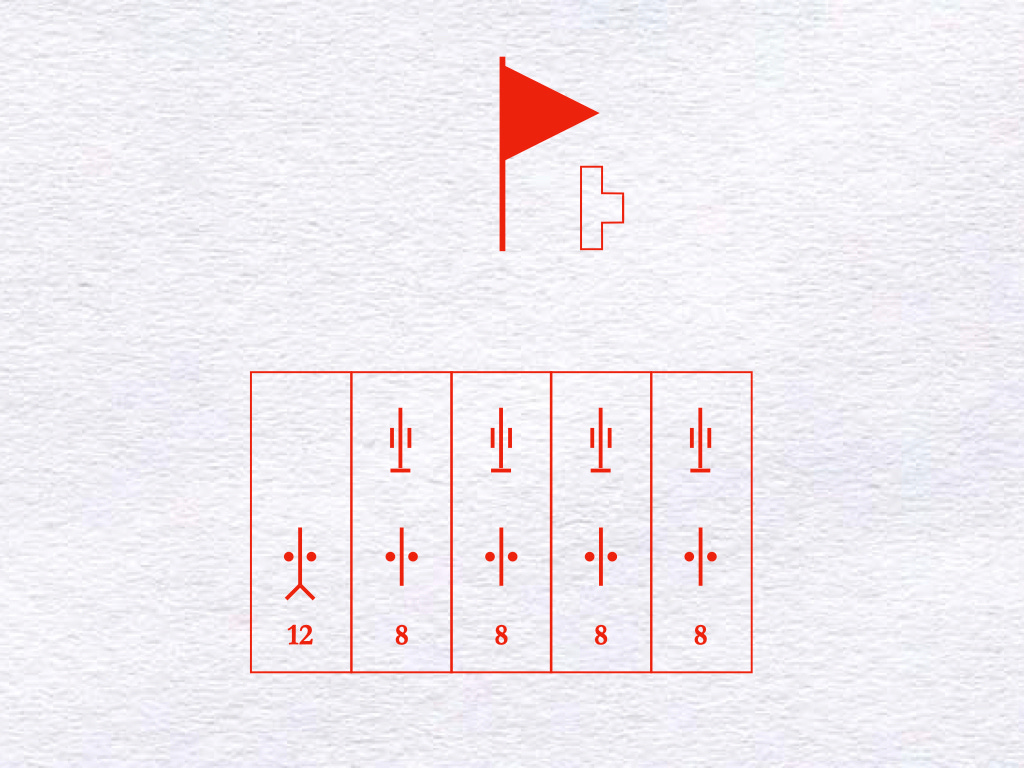

While the tripod-mounted machine guns of French battalions fighting in Morocco were often distributed among the rifle companies, Clément-Grandcourt believed that the machine gun company serving in Syria would, more often than not, be employed as a single unit. At the same time, he had come to the conclusion that the sixteen-gun machine gun company that emerged from the war on the Western Front was too large for operations in the Levant. He therefore reduced to twelve that the number of tripod-mounted machine guns in the machine gun company of his proposed battalion.

Standard French machine gun companies were divided into two half-companies (peletons), each of which was made up of two platoons (sections.) Each machine gun platoon, in turn, consisted of a pair of two-gun squads (groupes), each of which was, as a rule, charged with firing upon a single target.

In the course of his service in France and Morocco, Clément-Grandcourt had come to believe that the practice of assigning a two-gun squad to each target failed to give the machine guns of the day sufficient time between bursts to allow their barrels to cool properly. He therefore organized the twelve machine guns of the machine gun company of his ideal battalion into four three-gun platoons (sections), each of which would constitute the smallest firing unit in the company.

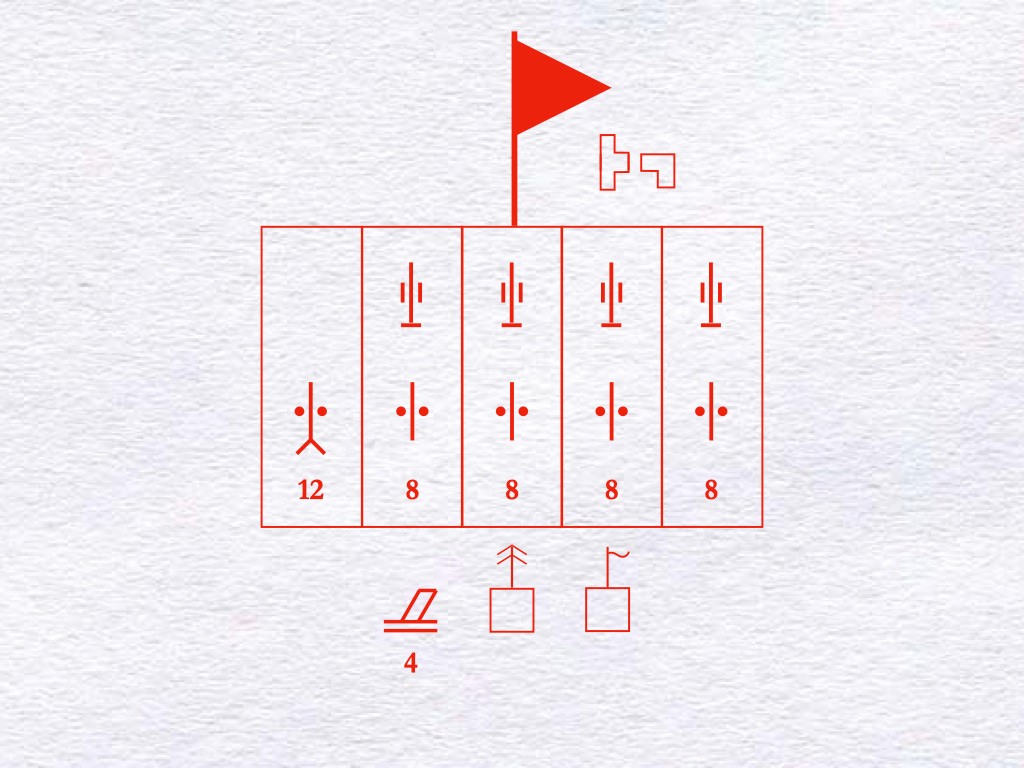

Clément-Grandcourt imagined his ideal battalion as both one of the three component battalions of a regiment and an autonomous unit (bataillon formant corps.) In the latter case, the battalion would be provided with a headquarters half-company (peleton hors rang) with two trench mortar platoons (sections), a platoon (section) of mounted scouts, a squad of communications specialists, and a squad of rangers (groupe franc).

If, however, the battalions served as part of a regiment, the regiment would possess a headquarters company (compagnie hors rang) with a “battery” (batterie) of six trench mortars and three machine guns; a platoon (section) of pioneers; a half-company (peleton) of mounted scouts; and a “platoon on foot” (section à pied) that, marvelous to say, would provide an organizational home to both the regimental signalers (la liaison) and a squad or two of rangers (groupe franc). The regimental headquarters company would be both the largest company in the regiment, as well as the most diverse. Clément-Grandcourt therefore recommended that command of the headquarters company be given to an officer who had displayed particular aptitude for such a challenge.

Source: Lieutenant-Colonel Clément-Grandcourt, ‘La Tactique d’après guerre et ses applications au Levant (VII): Organisation, Armament, Outillage’ [‘Tactics after the War and its Application in the Levant (VII): Organization, Weapons, Equipment’] Revue d’Infanterie, Volume 66, Numero 397 (octobre 1925) pages 556-585

For More About French Forces in Syria:

For More About Three-Piece Machine Gun Units:

To Support, Share, or Subscribe: