When, on 5 August 1914, the Expeditionary Force was mobilized, its two component army headquarters were mobilized with it. As had been the case with the pre-war exercises, the great training command at Aldershot provided the First Army with a complete staff while officers from many different commands assembled to form the staff of the Second Army. 1

Within hours of being mobilized, the character of these headquarters began to change. The first step in this process was the decision to reduce the strength of the first contingent of the Expeditionary Force by two infantry divisions. One of these divisions (the 4th Division) was to remain in the United Kingdom for a week or two. The other division (the 6th Division) was to stay at home until such time as the Territorial Force was deemed ready to deal with a hostile landing.

This decision, taken by an ad hoc committee of senior political and military leaders that met on 5 and 6 August 1914, was not entirely unexpected.2 The possibility of devoting a portion of the Expeditionary Force to home defence had been extensively discussed before the outbreak of war.3 The implication of this decision for the two army headquarters, however, had not.

The deployment plans drawn up earlier in 1914 called for the 1st, 2nd, and 4th Divisions to begin the war as part of the First Army while the 3rd, 5th, and 6th Divisions formed the Second Army.4 Holding back the 4th and 6th Divisions thus had the effect of cutting the strength of each army by a third.5 It also deprived the British Empire of one of its more intriguing strategic options, the concentration of the Expeditionary Force near Antwerp in order to operate against the exposed right flank of the German forces marching through Belgium.

In the view of the aforementioned committee, a cut-down Expeditionary Force would not be strong enough to fight its way into Antwerp, let alone make much of an impact upon the Germans once it got there. Reduced to four infantry divisions and five cavalry brigades, the Expeditionary Force could thus best be employed as an appendix to the long line of French divisions then being concentrated along the Franco-German frontier. That is to say, rather than being an independent force of two small armies, it was to be what French war plans called Armée W, a flank guard consisting of the rough equivalent of two French army corps and two French cavalry divisions.6

This epiphany was quickly followed by the decision to form the infantry divisions of the Expeditionary Force into three army corps.7 The first two of these would be created by the simple act of renaming the First and Second Armies as I Army Corps and II Army Corps. (The latter titles would soon be abbreviated as I Corps and II Corps.) The remaining army corps would remain in the British Isles until at least one of the divisions held back for home defence was ready to cross the Channel. This would give it time to improvise an army headquarters and an army headquarters signal company, as well as to plan for its eventual employment overseas.

Many narratives that deal with despatch of British troops to the Continent, including those published as part of the official History of the Great War, make no mention of the two component armies of the Expeditionary Force. Instead, the authors of these accounts adopted the convention of retroactively applying the term “army corps,” thereby sacrificing a degree of technical accuracy in order to preserve their readers from a change in terminology. Most biographers of personalities involved in the events of the summer of 1914 followed this same practice, as did the senior officers who wrote autobiographical accounts. 8 Nonetheless, it is clear from the orders issued by General Headquarters that it took a fortnight or so for the new nomenclature to be fully accepted by the Expeditionary Force. 9

The first of the daily operations orders issued by General Headquarters to consistently use the term ‘army corps’ to refer to the two intermediate headquarters was issued on 21 August. In the operations order issued on the previous day, the text of the basic order had referred to the two intermediate formations as ‘armies’. The explanatory tables attached to the orders, however, had called them ‘army corps’. 10

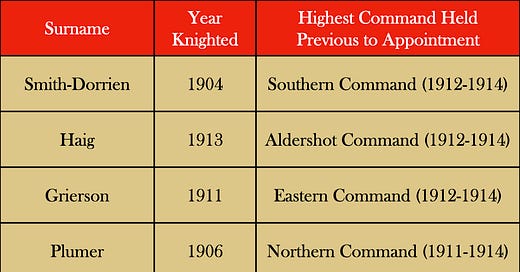

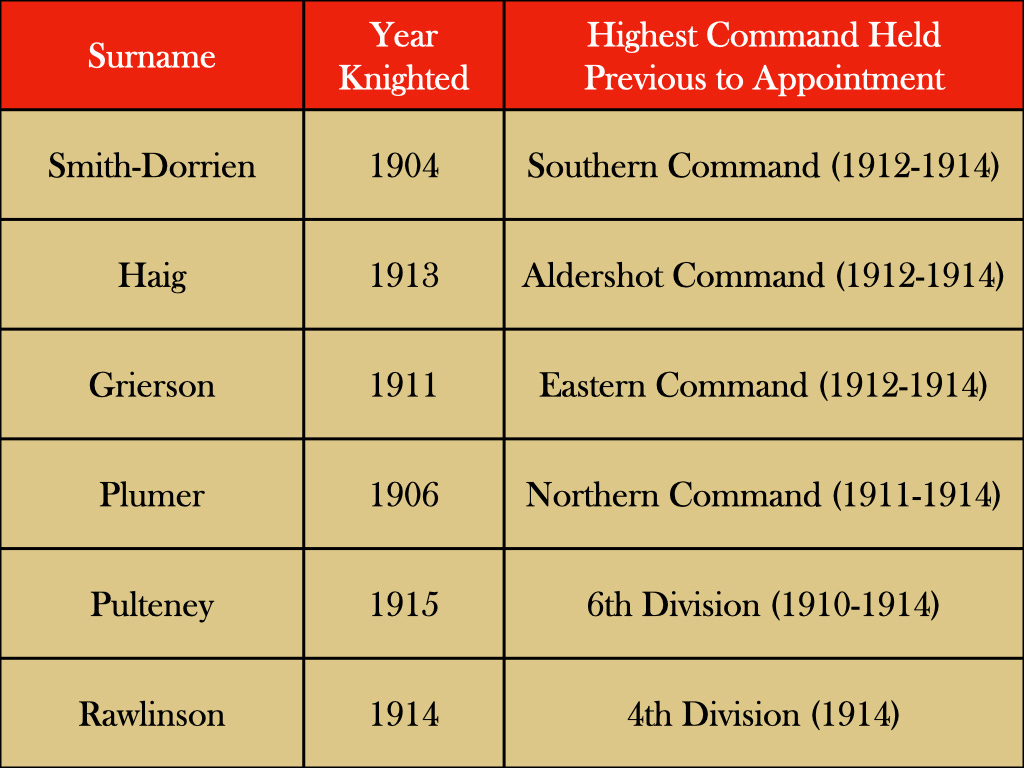

The last act that was fully consistent with the old practice of forming two armies within the Expeditionary Force was the appointment, on 18 August, of Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien to take command of the recently re-christened II Corps.11 Like Haig and Grierson, Smith-Dorrien was a highly respected lieutenant general with a long history of involvement in efforts to modernise the British Army. He was, in short, an officer who possessed both the skills and the stature usually associated with the command of an army. The next general to take command of an army corps within the Expeditionary Force was an officer of a very different sort. Major General William P. Pulteney, who took command of the newly formed III Corps, was roughly the same age as Haig, Grierson, and Smith-Dorrien, but substantially junior in rank.12

While the three lieutenant generals were military intellectuals, men who had written manuals and designed organizations, Pulteney was well known for his lack of interest in the more cerebral side of soldiering. Similarly, while Haig, Grierson and Smith-Dorrien had all taken great pains to study the handling of large combined-arms formations, Pulteney had managed to avoid both a pre-commissioning course (such as the ones offered by the Royal Military College at Sandhurst or the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich) and the Staff College. 13

The ambiguous position of the new army corps at the start of the war can be seen in an exchange of notes between Sir John French and Sir Ian Hamilton. (Hamilton was then a full general who had just been given command of all of the land forces in the British Isles.)14 On 17 August 1914, he sent a telegram to Sir John French asking to

be named as Grierson’s successor. The next day, French replied with a letter telling Hamilton that he was far too senior for such job. "Having regard to the vast importance of your present command, and the great necessity for the presence as C. in C. [commander-in-chief] in England of a man of your rank and experience of war, I feel that it would not be exercising a due economy of command power to put you in the place of junior officers who are fit to command an Army Corps."

French drove home this point by informing Hamilton that the soon-to-be- formed III Corps would only consist of two infantry divisions and that its commanding general was to be Major General Pulteney.15 What French did not tell Hamilton was that his preferred choice for Grierson’s replacement was Lieutenant General Sir Herbert Plumer, a man who was far closer to Haig, Grierson and Smith-Dorrien in terms of both seniority and stature than he was to Pulteney.16

Horace L. Smith-Dorrien, Memoirs of Forty-Eight Years’ Service, (London: John Murray, 1925), page 378

Sometimes called the ‘Council of War’, this meeting was attended by the principal cabinet ministers, senior officers of the military and naval staffs and Horatio H. Kitchener, who accepted the post of secretary of state for war on the second day of deliberations. Edmonds, Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914, I, page 29.

For a brief description of the “invasion crisis” of 1913, see Holmes, The Little Field Marshal, pages 148-49.

Detrainment and Billeting Tables, 1914, TNA, WO 106/49B/5 The assignment of divisions to the two armies was particularly pleasing to the Scottish sensibilities of Sir James Grierson, for it placed battalions of the Royal Scots, Royal Scots Fusiliers, Gordon Highlanders, King’s Own Scottish Borderers, and Cameron Highlanders, under his command. “How fine,” he wrote, “the massed pipes will sound.” Macdiarmid, The Life of Lieutenant General Sir James Montcrieff Grierson, pages 256-257.

The cavalry, consisting of the four brigades of the Cavalry Division and the independent 5th Cavalry Brigade, formed a separate command within the Expeditionary Force.

A French cavalry division of 1914 (with six cavalry regiments and twelve field guns) was only half as large as the Cavalry Division of the original Expeditionary Force (with twelve cavalry regiments and twenty-four field guns.)

Edmonds, Military Operations, France and Belgium, 1914, I, page 7.

A notable exception to the tendency to ‘backdate’ the creation of the army corps of the Expeditionary Force is the biography of Sir James Grierson, who briefly commanded the Second Army at the very start of the war. In this work the term '“army” is used throughout the discussion of the fortnight that passed between the start of the war and Grierson’s untimely death on 17 August 1914. MacDiarmid, The Life of Lieutenant-General Sir James Moncrieff Grierson, pages 256-57.

Upon mobilization, the paper construct described in the War Establishments as “a general headquarters” became a flesh-and-blood proper noun that no longer required an indefinite article.

Edmonds, Military Operations, France and Belgium, 1914, I, pages 452-459. An “army headquarters signal company” consisted of the permanent “headquarters of an army headquarters signal company” and whatever autonomous airline or cable platoons might be attached at the moment. (The sole wireless section was usually attached to the signal company headquarters belonging to General Headquarters, where it served primarily to maintain contact with the Cavalry Division.)

For most of the two years preceding the outbreak of war, Smith-Dorrien had been earmarked to command the Second Army. On the very eve of war, however, he was replaced by Grierson. For a somewhat acerbic explanation of this event, see Basil Collier, Brasshat: A Biography of Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, (London: Secker-Warburg, 1961), pages 136-137.

Haig, Grierson, Smith-Dorrien and Pulteney were all born between 1858 and 1861. Beckett, ed., The Army and the Curragh Incident, 1914, “Biographical Notes.”

One need not fully embrace the characterization of Charles Bonham-Carter (“the most completely ignorant general I served under during the war and that is saying a lot”) to see the gulf that separated Pulteney from Haig, Grierson and Smith-Dorrien. The quotation from Brigadier General Bonham-Carter comes from John M. Bourne, Who’s Who in World War One, (London: Routledge, 2001), page 239.

Hamilton’s command included the three “armies”of the Central Force, a sizable reaction force designed to support the network of home defence garrisons guarding ports and stretches of coastline. The smallest of these armies, the First Army, had but one infantry division and a single mounted brigade. The largest, the Third Army, had four infantry divisions and two mounted brigades. Edmonds, Military Operations, France and Belgium, 1914, II, page 5.

Letter of Sir John French to Sir Ian Hamilton, 18 August 1914, reproduced in Gerald French, editor, Some War Diaries, Addresses and Correspondence of Field Marshal the Right Honourable the Earl of Ypres, (London: Herbert Jenkins, 1937), page 146.

Extract from the diary of Sir John French, entry for 17 August 1914, reproduced in French, editor, Some War Diaries, p. 146.