The plans that guided the initial mobilization of the British Expeditionary Force made no provision whatsoever for army corps of the French or German variety. Indeed, one can read every line of the War Establishments in effect at the time of mobilization without making a single sighting of the term “army corps.”1 Instead, the careful reader will encounter such unusual creatures as the “squadron of Irish Horse,” the “headquarters of an army (a group of two or more divisions),” and the “headquarters of an army headquarters signal company.” Curious as they were, these unusual organization were artifacts of an even stranger product of the military imagination, a formation so bereft of the customary trappings of an army corps that its creators called it something else.2

This initial poverty was not, however, without its advantages. In the course of the first year of the First World War, the French and German Armies replaced their permanently constituted, regionally recruited, rigidly organized binary army corps with triangular formations organized upon the principle of modularity. Though not necessarily triangular, the British “army (a group of two or more divisions)” was modular from the very start of the war. This meant that the development of the British army corps in the first year of the First World War was a comparatively smooth process, a matter of adding new features to a simple framework rather than an act of “creative destruction” of the kind required to reform French and German army corps.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the British Army made frequent attempts to include army corps of various sorts in its organizational schemes. The earliest of these attempts was also the most successful. In the Waterloo campaign of 1815, the main striking force of the Duke of Wellington’s army consisted of two army corps, each of which comprised four British or Allied infantry divisions and a substantial cavalry formation. After Waterloo, however, most British army corps were paper formations, unfamiliar features of abstract mobilization plans that bore little connection to either units in garrison or the expeditionary forces formed to fight major wars.

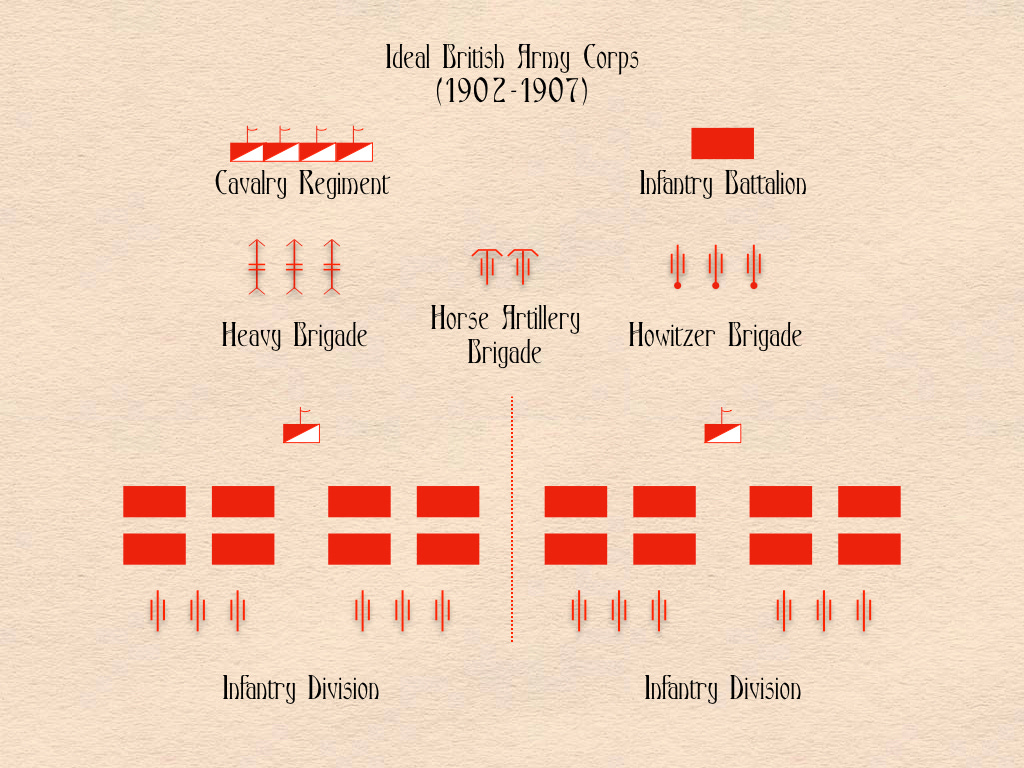

Between the end of the Second Boer War and the formation of the Expeditionary Force, most of operational units of the British Army located in the British Isles, whether of the Regular Army, the Volunteers, or the Militia, were formed into six small army corps. On theory, each of these formations consisted of two small divisions, a small corps artillery, a cavalry regiment, and a spare infantry battalion. In practice, the higher the number of each corps, the greater the proportion of units composed of part-time soldiers and the smaller the number of artillery batteries.3

The few army corps that made forays into the three-dimensional world were peacetime commands of various kinds. These, however, lay lightly upon the unavoidably ad hoc reality of an army that, at any given time, might find itself pulled in many different directions. Indeed, none of the British armies sent overseas between 1815 and 1914, whether to fight in the Crimea, Egypt or South Africa, had been divided into army corps.4 Because of this, many prominent members of military and political circles came to associate the very term “army corps” with martial pedantry of the most impractical sort, an artifact of fanciful schemes for recasting the British Army in an alien mould rather than an indispensable tool for the handling of modern armies.5

Though less sophisticated opponents of the army corps might have been satisfied with a mere change in nomenclature, those who drew up the plans for the Expeditionary Force provided it with an organizational architecture that dispensed, entirely and explicitly, with army corps of the Continental type. Functions performed by French or German army corps of the day were assigned to different echelons. Thus, work that would have been done by the heavy howitzer batteries of a German army corps was instead divided between the heavy batteries of British infantry divisions and the medium siege batteries of an autonomous siege train. The logistics and engineering services that German soldiers identified so closely with army corps were likewise split between divisional organizations and “army troops” – units that were assigned directly to the Expeditionary Force as a whole. The duties performed by the cavalry regiments assigned of French army corps were fulfilled by another army troops organization, the independent mounted brigade.6

Providing the Expeditionary Force with eight or more autonomous formations (six infantry divisions, a cavalry division and one or two independent brigades) gave it an unusual degree of organizational flexibility. Faced with a task that required more than one army corps but less than two, the commanding general of a French or German field army often found himself on the horns of a dilemma. If he broke up a corps in order to obtain a third division, he inflicted all sorts of organizational violence upon the structure of that formation. If, on the other hand, he sent two corps to do the work of one-and-a half, he committed the crime of gross inefficiency.

The “general officer commanding-in-chief” of the Expeditionary Force, however, faced no such problem. The building blocks that he used to assemble task forces were both smaller and handier than French or German army corps. If he needed one, three or five divisions for a mission, he could assemble them into a task force without having to break apart any other formation, reshuffle his artillery, or split a corps-level cavalry regiment in two. Indeed, the chief difficulty that the leadership of the Expeditionary Force would have to overcome when assembling a task force would be providing it with a suitable headquarters.

To Subscribe, Support, or Share:

War Office, War Establishments, Expeditionary Force, 1914, (London: HMSO, 1914), pages 28, 69, and 137

The South Irish Horse and North Irish Horse were mounted regiments of the Special Reserve. E.A. James, British Regiments, 1914-1918, (Heathfield: Naval and Military Press, 1978), page 15 and Report of the Committee on War Establishments (Home), 1912, TNA, WO 33/612.

John K. Dunlop, The Development of the British Army, 1899-1914, (London: Methuen, 1938), pages 130-140

Some of the forces sent out to South Africa in 1899 were assigned to a formation that was variously called “the Field Force,” “the First Army Corps,” and the “Army Corps.” This assemblage, however, did not long survive the start of the campaign. For descriptions of this formation, see Dunlop, The Development of the British Army, page 72.

The most prominent of British opponents of army corps army corps was Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, who served as prime minister at the time that the plans for the Expeditionary Force and other aspects of the Haldane Reforms were being drawn up, debated, approved and implemented. Twice secretary of state for war, Campbell-Bannerman was once quoted as saying, “Sir, the expression ‘Army Corps’ is like the great word ‘Mesopotamia.’ It is a blessed word. It deludes the convert and imposes upon the simple.” Dunlop, The Development of the British Army, page 136.

The mounted brigades of the Expeditionary Force were independent formations that consisted of a battery of horse artillery, a cavalry regiment, a mounted infantry battalion, and a third mounted unit could either be a second regiment of cavalry or a second battalion of mounted infantry. (Though similar to cavalry regiments in size and structure, mounted infantry battalions got no training whatsoever in the art of mounted combat. Instead, they were designed to follow in trace of cavalry units, dismount at a suitable location, and support the cavalry with a heavy volume of rifle fire.) War Office, War Establishments, Part I, Expeditionary Force, 1913, (London: HMSO, 1913), p. 271. Late in 1913, the 5th Cavalry Brigade replaced the two mounted brigades. See, among others, Anonymous, “Les Forces Militaires Anglaises en 1913,” Revue Militaire des Armées Étrangères, September 1913, pages 193-195.