The documents that promulgated the initial design for the Expeditionary Force made no provision for the kind of headquarters that would be needed by a task force composed of two or more divisions. Neither the Special Army Order of 1 January 1907 that laid out the organization of the Expeditionary Force nor the explanatory memorandum published with it made any mention of an organization that might fill this role. 1 On the contrary, these documents explicitly enshrined the division as the largest subordinate formation of the Expeditionary Force. Similarly, the first two editions of the War Establishments to appear after the creation of the Expeditionary Force, those published in January 1907 and June 1908 included a detailed description of the “headquarters of an army,” an organization that was clearly designed for the Expeditionary Force as a whole. They were entirely mute, however, on the subject of intermediate headquarters.2

In April 1909, this silence was broken by two sentences that appeared in the version of the Field Service Regulations that appeared that month. After defining the division as “complete in itself with every requisite for independent action,” the manual added that “they may be grouped in accordance with the particular conditions of the campaign in two or more armies, each under a separate commander, all under the supreme command of the C-in-C [commander-in-chief]. To each army so formed is allotted a proportion of army troops comprising cavalry for protective duties, intercommunication troops, and the necessary administrative services for their maintenance.”3

In keeping with the dictates of the Field Service Regulations, editions of the War Establishments published after the spring of 1909 were adjusted to reflect the new distinction between the Expeditionary Force as a whole and the subordinate armies that might be formed within it. In the revised War Establishments published in December 1909 and January 1911, this was entirely a matter of adding a single line to the top of the list of “army troops” contained in each volume.4 Whereas this list had previously begun with the “headquarters of an army,” top billing would henceforth go to the “general headquarters.”5 (The “headquarters of an army” remained on the list, but it had been demoted to second place.)

However, as these two editions lacked any description at all for the headquarters of a formation larger than a division, readers had to wait until 1912 to get a sense of what exactly was meant by this change of nomenclature. In that year, the fifth edition of the War Establishments to be published since the establishment of the Expeditionary Force provided complete tables of organization for both the “general headquarters” and the “headquarters of an army.” By making it clear that the “general headquarters” was several times as large as the “headquarters of an army” and by giving the latter the subtitle of “a group of two or more divisions,” the 1912 edition of the War Establishments erased any doubts that anyone might have had about the difference between the two types of organization.6

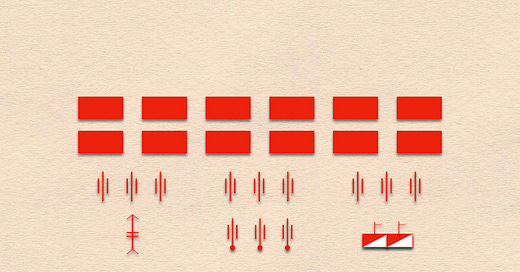

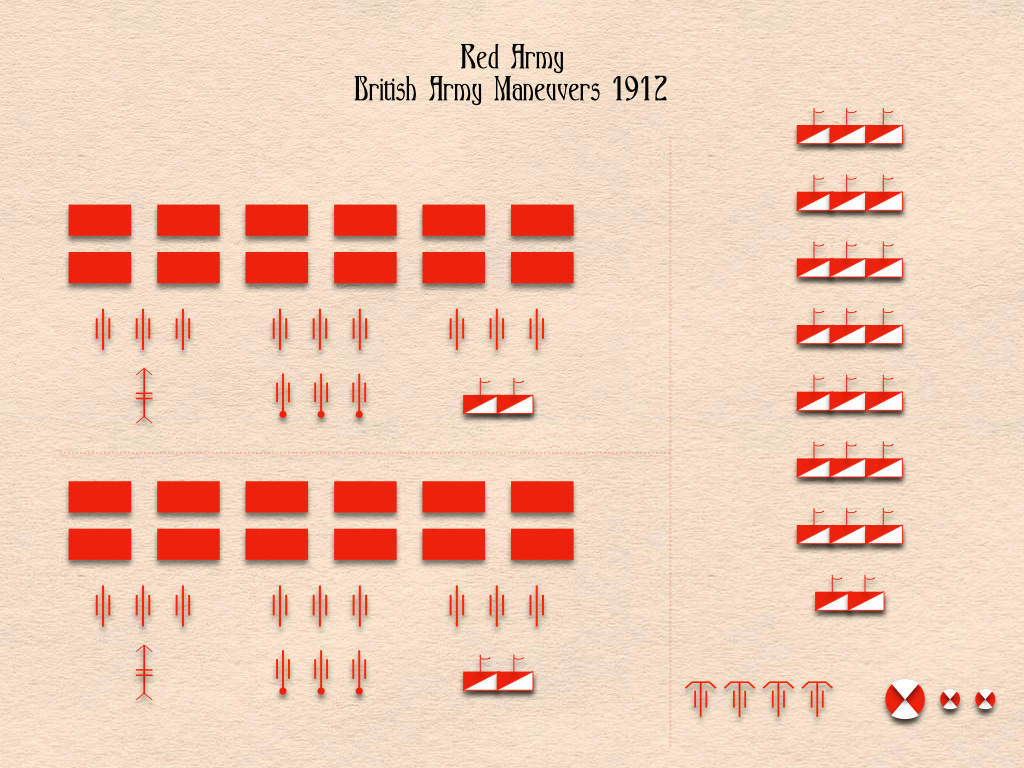

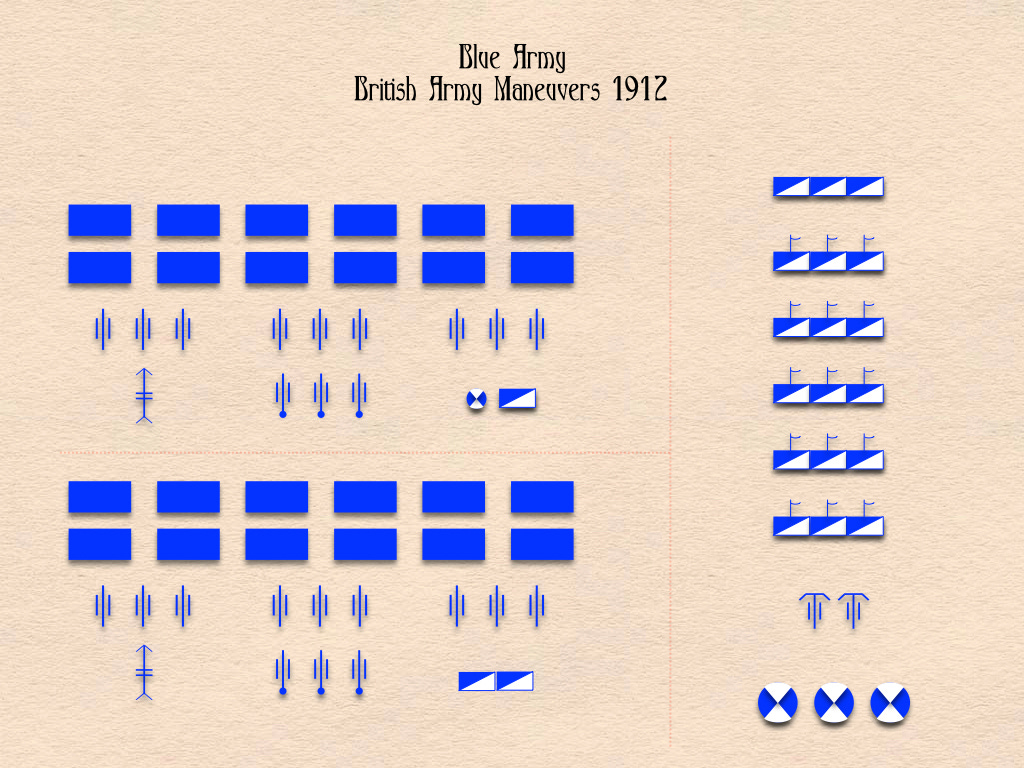

The new army headquarters of the Expeditionary Force made their first major public appearance in the army maneuvers of 1912. In this exercise, a Red Army consisting of an army headquarters, two infantry divisions and a cavalry division took the field against a similarly organized Blue Army. The headquarters of the Red Army was formed from the staff of the Aldershot Command, an organization that had previously served as the only standing army corps headquarters in the British Army. That of the Blue Army, like the army corps headquarters assembled for maneuvers in the years prior to 1907, was made up of officers on loan from other regional commands.7

The following year saw the two army headquarters on the same side. In September 1913, a scripted exercise gave Field Marshal Sir John French a chance to practice the handling of a surrogate for the Expeditionary Force that was nearly twice as large as each of the two armies that took part in the 1912 maneuvers. This Brown Force consisted of a general headquarters, a cavalry division and two armies. Each army, in turn, consisted of a headquarters and two infantry divisions.8

The combatant units that took part in the scripted maneuvers of 1913 were, for the most part, considerably weaker than they would be at mobilization. The infantry battalions had less than a third of the men they needed to be ready for war, the field artillery batteries but half of their wartime allotment of artillery pieces. At the same time, both the general headquarters and the army headquarters had been brought up to their full war establishments.

The key jobs within each headquarters, moreover, were assigned to the officers most likely to take those positions upon mobilization. Thus, Field Marshal Sir John French, who had already been selected to take charge of the Expeditionary Force in the event of war, commanded the Brown Force. Likes the officers designated to lead the subordinate armies of the Expeditionary Force, Lieutenant General Sir Douglas Haig and Lieutenant General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, were placed at the head of the two subordinate armies of the Brown Force.9

Late in 1913, the position of the army headquarters within the structure of the pre-war Expeditionary Force was consolidated by a reformation of the signal service that kept the General Headquarters in touch with its subordinate formations. Between 1907 and 1913, the organization of this service was an ad hoc affair. Mobilization plans provided senior signals officer of the Expeditionary Force with five signal companies. 10 Broken down into detachments of various sorts, these gave him the means to tailor a communications infrastructure to the needs of the moment.11

In 1914, this ad hoc system was replaced by a modular design. A permanent signals unit was created for each of the three largest formation headquarters of the Expeditionary Force – the General Headquarters and headquarters of the two armies. Each of these units, known as ‘headquarters of a general headquarters signal company’ or ‘headquarters of an army headquarters signal company’ provided a signal office for its affiliated formation and a motorcycle dispatch rider service.12 Each signal company headquarters also provided points of attachment for autonomous platoons that specialized in different ways of connecting the various signals offices to each other.13

Dunlop, The Development of the British Army, pages 261-262

War Office, War Establishments for 1907-1908, (London: HMSO, 1907), pages 24-25.

General Staff, Field Service Regulations, Part II, Organization and Administration, (London: HMSO, 1909), pages 24-25

“Army troops” consisted of units of the Expeditionary Force, some as small as companies and some as large as brigades, that were not permanently assigned to divisions.

War Office, War Establishments for 1907-1908, page 14; War Establishments for 1908-1909, (London: HMSO, 1908), page 14; War Establishments for 1909-1910, (London: HMSO, 1909), page 14 and War Establishments for 1910-1911, (London: HMSO, 1911), page 14

War Office, War Establishments for 1911-1912, (HMSO, 1912), pages 16-24.

A brief description of the army maneuvers of 1912 can be found in Duncan S. MacDiarmid, The Life of Lieutenant-General Sir James Moncrieff Grierson, (London: Constable and Company, 1923), pages 244-246.

An extensive discussion of this exercise can be found in Raoul de Thomasson, “The British Army Exercise of 1913”, The Army Review, January 1914.

Richard Holmes, The Little Field Marshal: A Life of Sir John French, (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 2004), page 148

Two of the signal companies were ‘air-line’ companies that specialized in stringing bare wire on telegraph poles. Two were ‘cable’ companies that laid insulated wire on (or under), the ground. One was a “wireless” company equipped with wagon-mounted radio sets. (The chief purpose of these radio sets was to maintain contact between the General Headquarters and the cavalry division.) Dunlop, The Development of the British Army, page 264 and Hubert Foster, Organization, How Armies Are Formed for War, (London: Hugh Rees, 1913), pages 79 and 92-93. Prior to 1910, the signal companies had been known as “telegraph companies.”

Anonymous, ‘Reorganization of the Intercommunication Services of the Expeditionary Force for War’, The Army Review, January 1912, pages 272-74

War Office, War Establishments, Part I, Expeditionary Force, 1914, pages 135-138

In August 1914, sixteen of these platoons were mobilized for the use of the Expeditionary Force. James Edmonds, Military Operations, France and Belgium, 1914, (London: MacMillan and Company, 1925), I, page 426