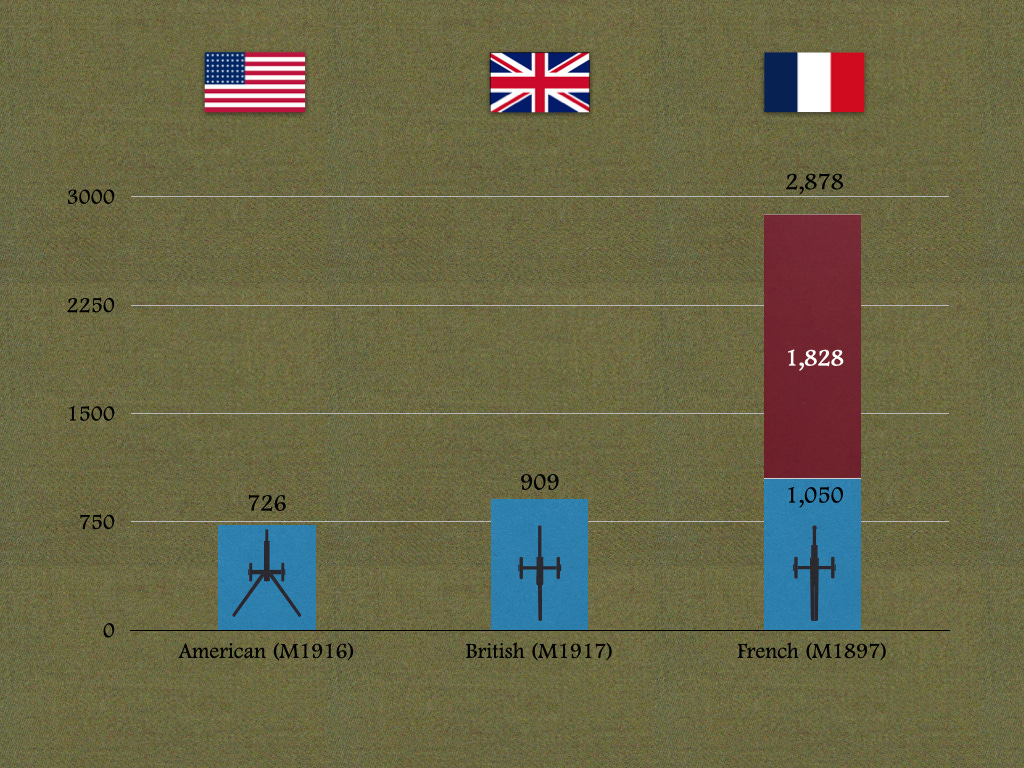

On 6 April 1917, when the United States declared war on the German Empire, neither the US Army nor the US Marine Corps possessed a single 75mm field gun. Two years later, the United States had accumulated 4,503 artillery pieces of that description. (Of these, 2,685 guns had been produced by American factories and 1,828 purchased from France.)1

The lion’s share of America’s stock of 75mm field guns consisted of “French seventy-fives.” Whether provided by France (1,828) or built in the United States (1,050), these were copies of a much celebrated model - that of 1897 - adopted by the French Army towards the end of the nineteenth century.

Of the remainder, a little more than half were “British seventy-fives.” Built by Bethlehem Steel, which had been making eighteen-pounder field guns for the use of the British Army, these were, in effect, British pieces that had been modified to fire French ammunition. Thus, the British seventy-five retained many of the distinctive features of the eighteen-pounder, the most obvious of which is the placement of the recoil mechanism on top of the barrel, rather than (as was the case with most field guns of the day) beneath it.

The smallest part of the American arsenal of 75mm field guns was composed of pieces of a type that some (but far from all) would come to call the “American Seventy-Five.” Like the British Seventy-Five, this weapon began life as a similar piece of a slightly different caliber. In this case, the antecedent was the second three-inch field gun of the American system of mobile artillery, a piece of recent vintage that had been provided with the latest thing in the design of gun carriages, a split trail.

The model number given to the British Seventy-Five, M1917, reflected the standard practice of naming an item of equipment after the year in which it had been adopted. The number given to the American Seventy-Five, which was also accepted into service in 1917, served a different purpose. As it was the same as that of its immediate predecessor (the M1916 three-inch gun), it reminded all concerned of the many similarities between the two pieces, especially where things like parts, accessories, and maintenance were concerned. Similarly, the fact that American-made versions of the French Seventy-Five bore the same model number as their French-built counterparts (M1897) showcased the interchangeability of the subassemblies (such as the carriage, the wheels, the barrel, and the recoil mechanism) between weapons built on different sides of the Atlantic.

While the barrel of the American Seventy-Five could be raised to an angle of 53 degrees, the barrels of the other two models were limited to less elevated elevations. (For the French Seventy-Five, the maximum elevation was 19 degrees. For the English Seventy-Five, it was 16 degrees.) This difference resulted from the provision of the American Seventy-Five with the relative novelty of a split trail. This same feature allowed the American Seventy-Five to swing its barrel horizontally by 23 degrees in each direction. (The comparable numbers for the French and British models were 6 and 4 degrees, respectively.)

The ability of a gun mounted on a split-trail carriage to raise its muzzle to higher heights offered a number of advantages. First, it facilitated direct fire against targets located at substantially greater elevations. (Such targets would include aircraft and troops upon a higher hill.) Second, it extended the distance a given shell propelled by a given amount of propellant could reach. (All other things being equal, a shell flew the furthest when the barrel in question was raised to an angle of 45 degrees or so.) Third, it provided a gun with some of the advantages enjoyed by mortars and howitzers. (This was especially true when the size of the propellant charges used was reduced.)2

Apart from the advantages offered by its split-trail carriage, the American seventy-five was not as up-to-date as the date of its design might suggest. In particular, it used of a recoil mechanism of a type (“hydro-spring”) that, in the course of the first three years of use on the Western Front, had proved itself inferior to the sort of recoil mechanism (“hydro-pneumatic”) fitted to the French seventy-five. (For one thing, the springs in the hydro-spring mechanisms quickly lost their ability to absorb the forces generated when the gun was fired. For another, even when the hydro-spring recoil mechanisms were new, they lacked the ability to return the barrel of a gun to the exact position it had occupied before firing. As a result, the gunner had to adjust his point of aim before dispatching the next round.)

To remedy this defect, the Ordnance Department provided a number of American seventy-fives with a hydro-pneumatic recoil mechanism. Developed in the by (or, at least, under the supervision of) Emile Rimailho, this mechanism might well be described as an updated version of the device that provided the French seventy-five with its remarkably high rate of fire.3 (In the 1890s, when he was a young artillery officer, Rimailho had played a central role in the design of the older apparatus.)

For Further Reading:

Benedict Crowell America’s Munitions: 1917-1918 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1919) page 71

For a discussion of the use of reduced charge ammunition with the M1896 75mm gun in French service, see Firmin-Émile Gascouin L’Évolution d’Artillerie pendant la Guerre (Pari: Flammarion, 1920) pages 108, 109, 113, 117, and 118. (For more on General Gascouin and his ideas, see Vincent Meyer, The Evolution of Field Artillery Tactics during, and as a Result of the World War (Student Paper, US Army Command and General Staff School, 1930).

Office of the Chief of Ordnance Handbook of Artillery (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1921) pages 83 and 84