The US System of Mobile Artillery

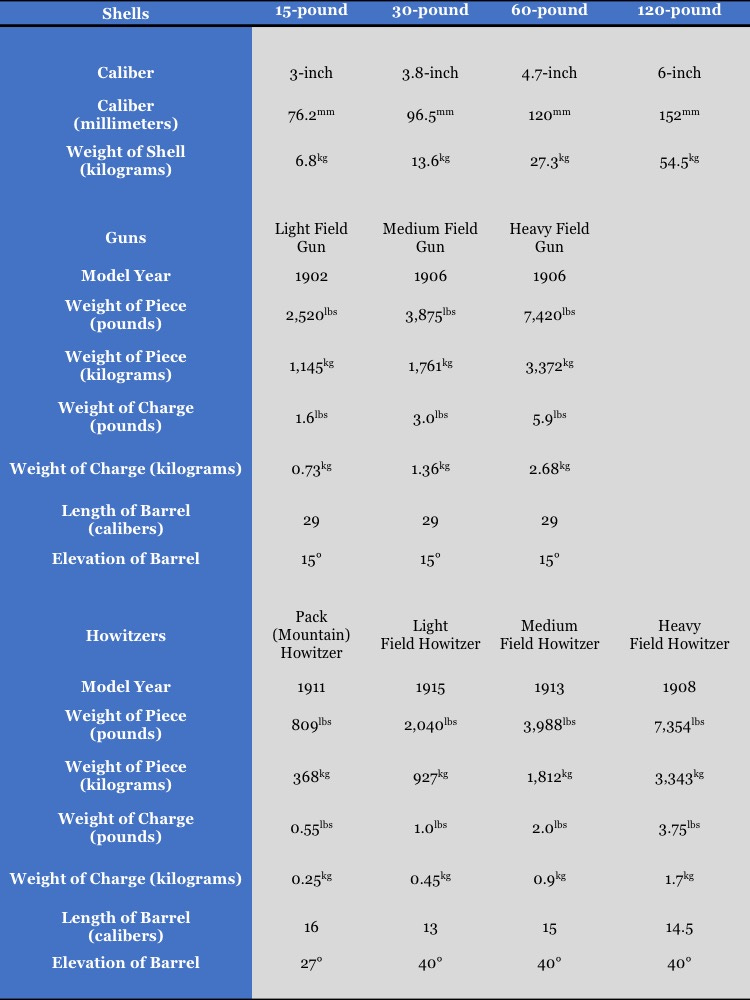

In the fifteen years leading up to the entry of the United States into the First World War, the Ordnance Department of the US Army developed a system of mobile artillery pieces based upon two principles. First, the artillery pieces of this system would make use of four projectiles, each of which weighed twice as the next lightest in the series. (The lightest of these shells would weigh 15 pounds. The heaviest would tip the scales at 120 pounds. In between these two extremes, the family featured a 30-pound shell and a 60-pound shell.) Second, the Ordnance Department proposed to build a pair of field pieces - one howitzer and one gun - for each of the shells in the series.

Once this project had been fully realized, the US Army would have been able to field three sets of weapons, each of which consisted of a pair of field pieces of similar weights. The first set would consist of a 15-pounder light field gun and a 30-pounder light field howitzer, the second a 30-pounder field gun and a 60-pounder field howitzer, and the third a 60-pounder heavy field gun and a 120-pounder heavy field howitzer.

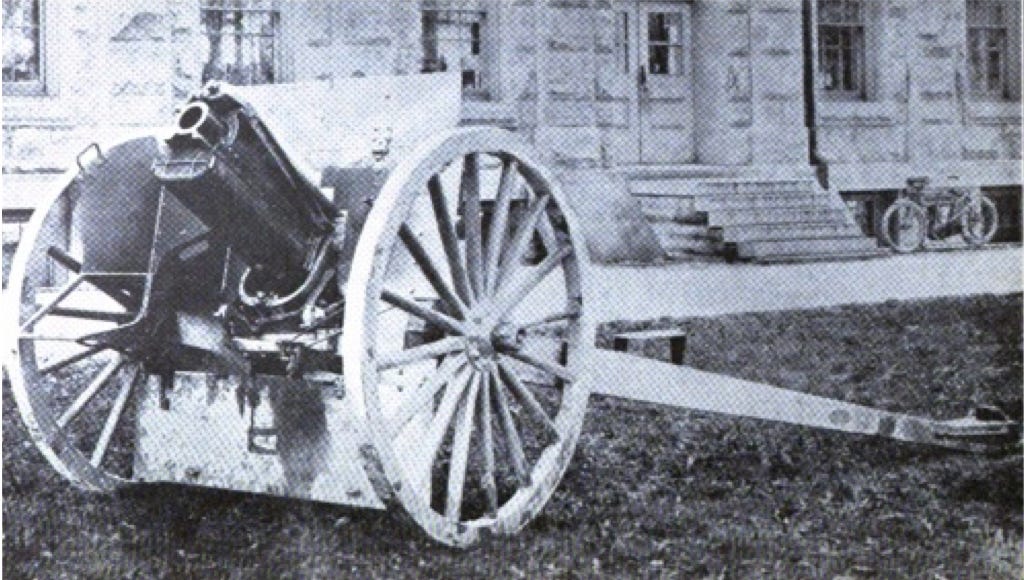

In addition to the three sets of field pieces, the Ordnance Department also developed a 15-pounder pack howitzer. Frequently described as a ‘mountain gun’, this weapon could be broken down into a series of loads, each of which was light enough to be carried by a mule. (The rule of thumb for such loads, derived from long experience with mules, was that each should not weigh more than 200 pounds.)

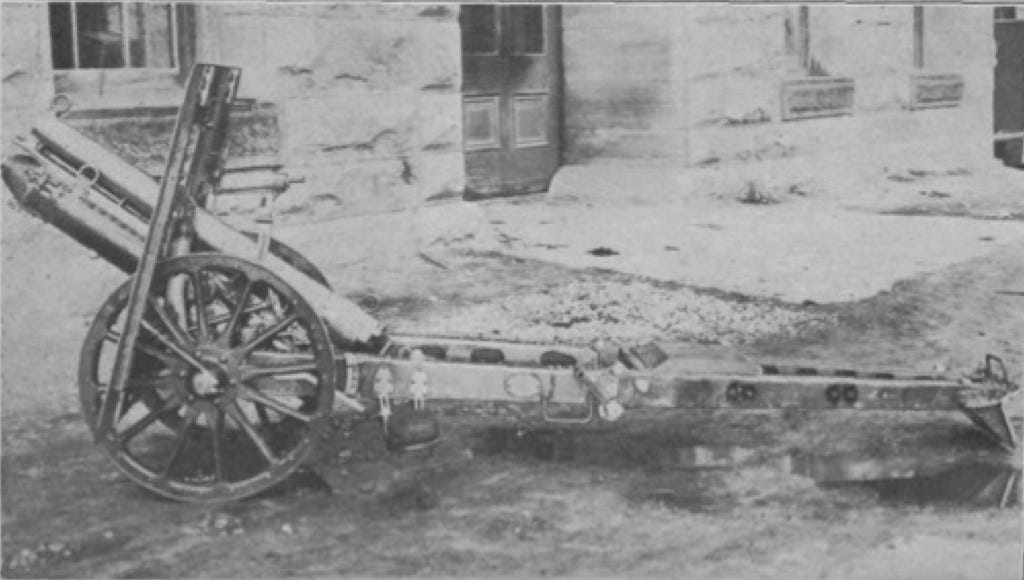

Between 1902 and 1915, the Ordnance Department built prototypes for all members of the ‘system of mobile artillery.’ In the same period, it put two members of the family, the 3-inch light field gun and the 4.7-mm heavy field gun, into serial production.

Upon the entry of the United States into the First World War, the Ordnance Department made plans to for the mass production of all guns and howitzers of the “system of mobile artillery.” However, by the end of 1917, this plan had been replaced by a program to arm most of the field artillery batteries of the American Expeditionary Force with French weapons, particularly the famous ‘French 75’ (75mm field gun Model 1897) and the Schneider heavy field howitzer (155mm Model 1917.) Indeed, while the 3-inch field guns armed batteries deployed along the border with Mexico, the only piece from the ‘system of mobile artillery’ to see service in France was the 4.7-inch heavy field gun.

Sources:

The first photo comes from the US National Archives. The other two were taken from issues of The Field Artillery Journal in the public domain.

Most of the figures in this table come from the following official publications of the U.S. Army Ordnance Department, all of which were published in Washington by the Government Printing Office: Handbook of Artillery (1920) pages 284 and 316; Handbook of the 3-inch Gun Matériel, Model 1902 (1917) pages 13 and 60; Handbook of the 3.8-inch Gun Matériel (1917) pages 9 and 17; Handbook of the 3.8-inch Howitzer Matériel, Model 1915 (1917) pages 11 and 37-38; and Handbook of the 4.7-inch Gun Matériel (1917) pages 9 and 34.

Figures for the 4.7-inch howitzer and 3-inch mountain howitzer come from two anonymous publications of the Bethlehem Steel Company: Mobile Artillery Material (South Bethlehem: M.S. Grim, 1916), pages 34-35 and 3-inch Mountain Gun and Carriage, Mark B (South Bethlehem: M.S. Grim, 1916), pages 6 and 10.

Figures for the 6-inch howitzer come from 108th (2nd Pennsylvania) Field Artillery Regiment, Field Artilleryman’s Guide (Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s Son, 1918), page 238.

For contemporary descriptions of the US “system of mobile artillery”, see the many books, articles, and locally published lectures produced by Oliver J. Spaulding, Jr. during this period, particularly The New Field Artillery Materiel … Its Characteristics and Powers (Fort Leavenworth: Staff College Press, 1905), pages 14-16; Artillery Weapons, (Fort Leavenworth: Infantry and Cavalry School, 1907), pages 18-21 and Notes on Field Artillery for Officers of All Arms (Fort Leavenworth: U.S. Cavalry Association, 1914), pages 53-58.

For Further Reading:

To Share, Subscribe, or Support: