Reconnaissance Pull

A Simple Illustration

Military folk are well-supplied with problems, but poorly provided with words. As a result, they often use the same word to describe different things.

Consider, if you will, the word “reconnaissance.” Sometimes, it describes a function, something that people do. At other times, it describes a type of unit. Thus, while a reconnaissance unit may be optimized to conduct reconnaissance, it will sometimes do other things. Likewise, outfits without “reconnaissance” in their names will often reconnoitre.

Over the past few years, asking one word to do double duty in this way has impeded understanding of “reconnaissance pull.” In particular, confusion between unit and function has led to the transformation of a technique for maximizing tempo into an inherently slower approach. That is, classic reconnaissance pull uses discoveries made in the course of combat to inform the employment of unengaged forces. One product of the aforementioned confusion, however, describes reconnaissance pull as “the reconnaissance method by which information derived from reconnaissance forces guides friendly force activities.”1

In the hope of clearing up this misunderstanding, I offer a simple illustration of classic reconnaissance pull.

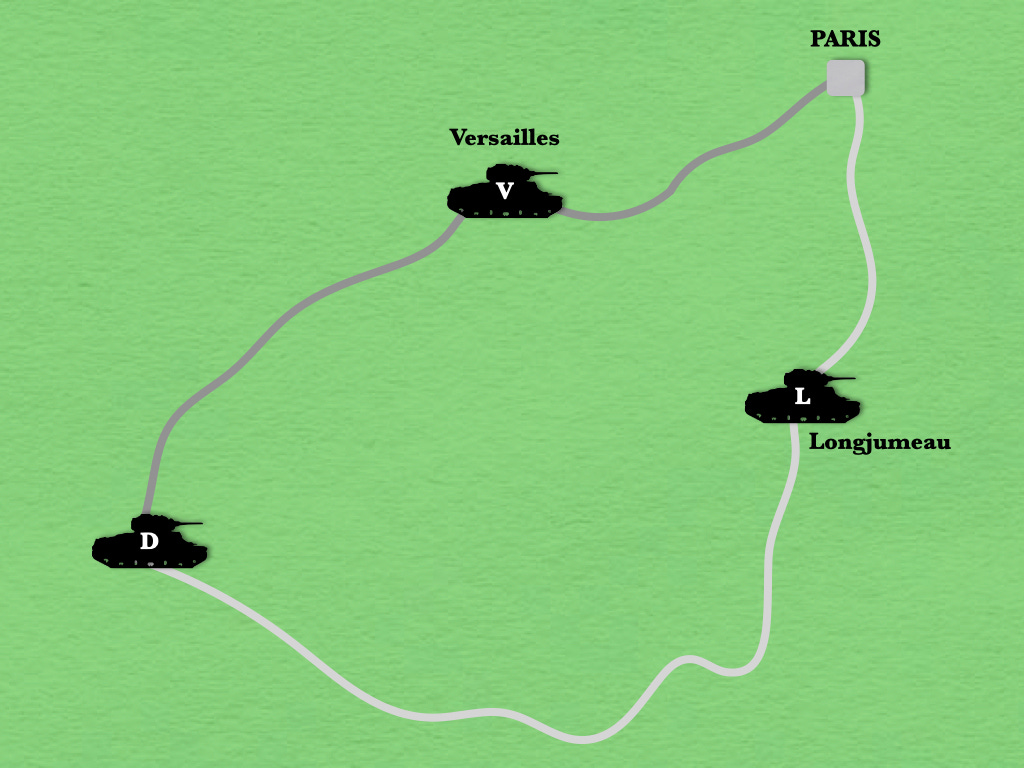

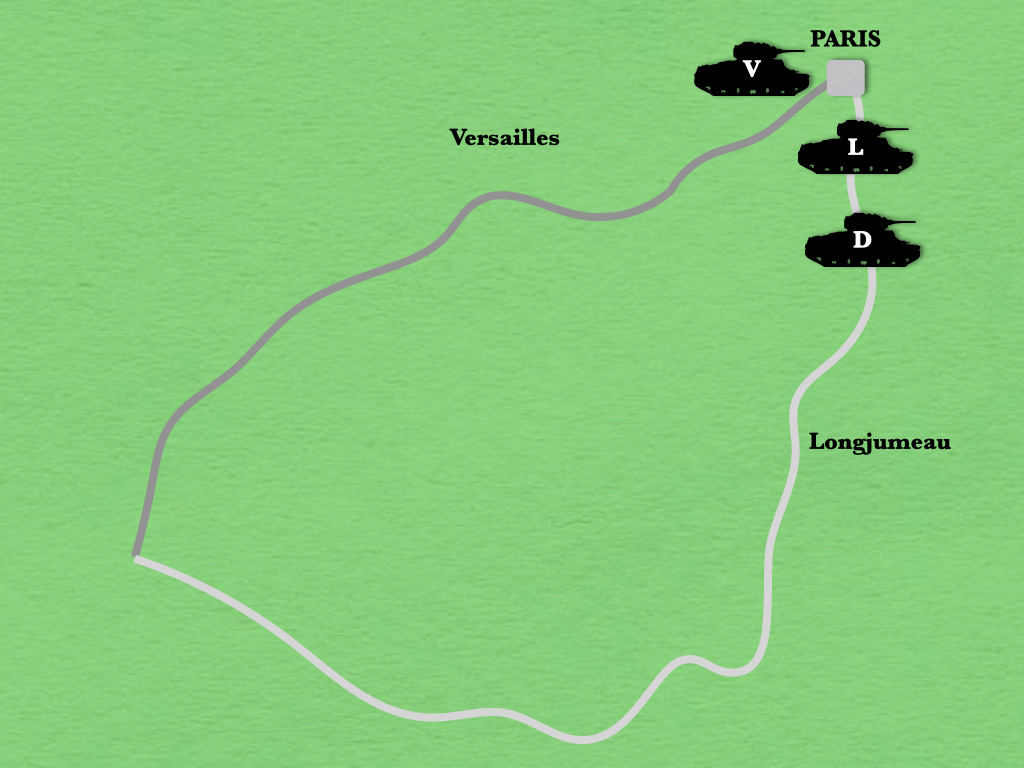

On 24 August 1944, the 2nd Armored Division of the French Army advanced towards Paris, in order to free that city from German control. One of the three task forces of the formation, Combat Command L, moved along a route that ran through the town of Longjumeau. Another task force, Combat Command V, traveled along the road that passed near the famous palace of Versailles. The remaining task force, Combat Command G, began the day in reserve.

The Versailles route was well supplied with roads. Better yet, it ran through open country that the Germans would find hard to defend. The Longjumeau route, however, lacked these advantages. Nonetheless, General Leclerc, in command of the division, declined to deploy his reserve until the resistance encountered by the two forward brigades gave him a better sense of German dispositions.

In the course of the day, radio messages from both of his forward task forces convinced Leclerc that, while German defenses on both routes were stronger than he had expected, those around Longjumeau were weaker than those in the vicinity of Versailles. He therefore used his reserve to reinforce Combat Command L.2

For Further Reading:

To Support, Share, or Subscribe:

MCWP 3-01 Offensive and Defensive Tactics (Quantico: US Marine Corps, 2019) page 12-12

M.P. Robinson and Thomas Seignon Division Leclerc (Oxford: Osprey, 2018) pages 32-34

Per FM 3-90, dated 01 May 2023: Reconnaissance pull is reconnaissance that determines which routes are suitable for maneuver, where the enemy is strong and weak, and where gaps exist, thus pulling the main body toward and along the path of least resistance. This facilitates the commander’s initiative and agility. Reconnaissance assets initially work over a broad area to develop the enemy situation.

The best stories of reconnaissance pull I’ve found are 62d/8th Guards Army* from 1944 - as the Reconnaissance tipped the Germans to reinforce the follow on attack happened within 1-2 hours, commanders and artillery officers forward, obviously assault echelons as well. Mind you at the Bug river they prepped the reconnaissance-pull-assault with very intense concentration of artillery. Reconnaissance in Force pull right into assault.

It worked repeatedly. The Germans couldn’t react in time, even the defense in depth was essentially penetrated and flanked before they could react.

*“The Fall of the 3D Reich” Vasily Chuikov.