Operations on a Broad Front

The war in Ukraine 2024

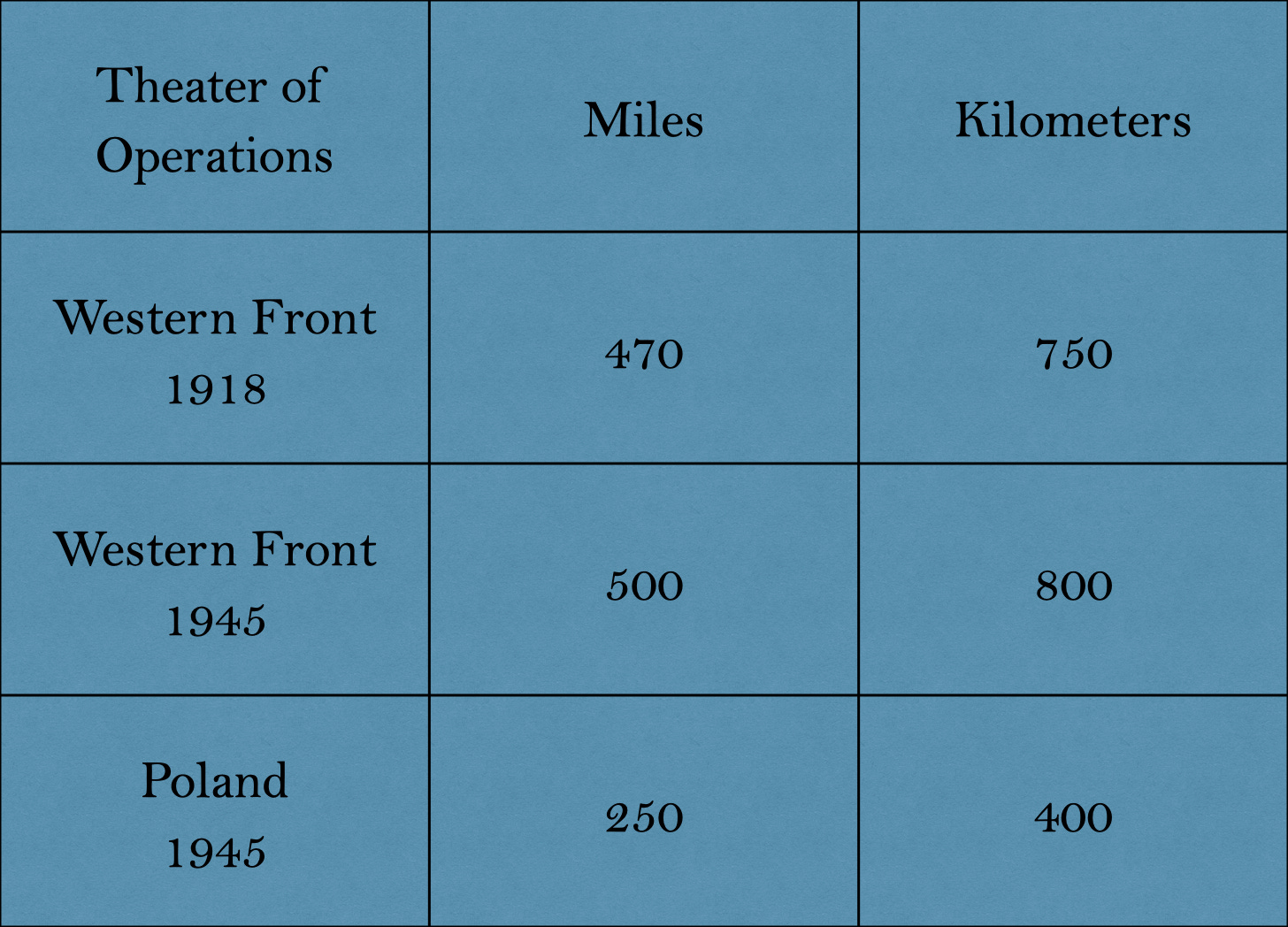

Towards the end of both of the great European wars of the past century, the eventual winners conducted operations on very broad fronts. During the last season of the First World War, the armies of the Allied and Associated Powers advanced along a wrinkled line of some 750 kilometers (470 miles.) In April of 1945, while the polyglot force commanded by Dwight David Eisenhower was repeating (and, indeed, exceeding) the achievements of its predecessor, three Soviet army groups launched simultaneous offensives along the full length of what is now the western border of Poland.

Armies able to attack in this manner enjoyed a peculiar advantage. By attacking everywhere at once, forces operating on a broad front made it hard for their enemies to employ their operational reserves. (One difficulty resulted from the time needed to move a substantial formation from one threatened spot to another. Another stemmed from the fact that, even if it achieved success, a reserve used in one place needed rest and refitting before it could be sent into action elsewhere.)

Of course, an attacker could only make use of this mechanism if it enjoyed the means to apply enormous combat power against several separate locations at the same time. Otherwise, the defender could divide his reserves into a number of “fire brigades,” each of which was sufficiently powerful to deal with a local crisis.1

The Possibility of Broad Front Operations in Ukraine

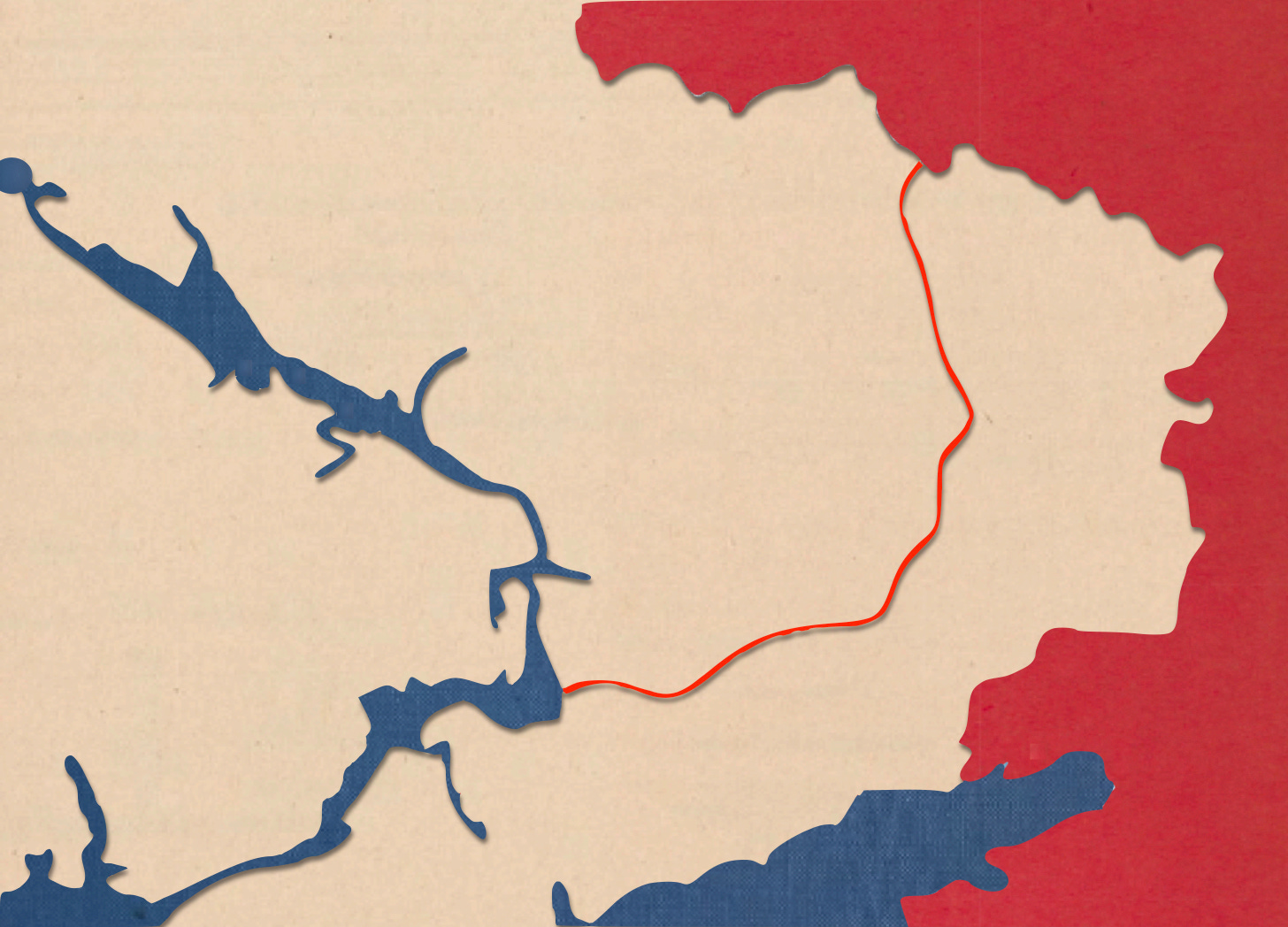

Since the end of the Ukrainian offensives of the fall of 2023, Russian armies in Ukraine have occupied a front with an approximate length of 410 miles (656 kilometers.) A good forty percent of this line, however, runs along the Dnipro. Thus, with a length of some 240 miles (384 kilometers) the frontage of the Russian groups forces that face foes on land within Ukraine resembles that of the three Soviet army groups that attacked out of Poland in the spring of 1945.

So far, the Russians have refrained from the sort of simultaneity that defines broad front operations. Instead, they have conducted a series of local offensives, such as those that resulted in the capture of Bakhmut and Avdiivka. Each of these, in turn, consisted of a long series of attacks with limited objectives.

The sequential character of both the local offensives and their component attacks owes much to the role played by field artillery. In order to conduct bombardments of sufficient ferocity, the Russians have been obliged to concentrate firing units and, in order to feed those batteries, build up local stockpiles of shells, rockets, and missiles. Likewise, the desire to dominate the airspace above the places where the gunners ply their trade and the logisticians deliver their loads has prevented the Russians from trying to do too many things at once.

The long series of local, one-at-a-time offensives may form part of what Alexander Mercouris has come to call a strategy of “aggressive attrition.”2 As such, they provide Russia with a direct means of achieving the frequently stated goal of the “demilitarization” of Ukraine. In other words, they serve to deprive Ukraine of men, money, and morale to the point where it loses the ability to maintain a substantial military establishment. Similarly, I suspect that there are those in the Russian camp who expect that a sequence of local defeats will, in and of itself, convince the Ukrainians to accept an otherwise unacceptable peace.

At the same time, local offensives are providing the Russians with both the skills and the infrastructure that they would need to conduct offensives like those conducted by the Red Army in the spring of 1945. Indeed, given the role played by this campaign in Russian military lore, and the place enjoyed by the resultant victory in the civic culture of the Russian Federation, I suspect that many Russian leaders, whether soldiers or civilians, look forward to a reprise of operations on a broad front.

For Further Reading:

To Subscribe, Support, or Share:

When discussing the work of local reaction forces, German soldiers who fought against the Soviets often used fire-fighting metaphors. For example, Infantry Division Großdeutschland, which frequently served as the reaction force of an army group, called its newspaper Der Feuerwehr [The Fire Department].

Brian Berletic Russian “Aggressive Attrition” Cracks Fortress Avdeevka New Eastern Outlook (20 February 2024)

Russia faces another limiting factor. It does not want to provoke further American/NATO intervention, especially when political support for Ukraine is declining. Dramatic advances might provoke a heavier response from the foreigners. The kind of grinding, day to day, un-telegenic attrition which is slowly putting Ukraine through the meat grinder may be the optimal way to win the war. Also, columns of tanks are precisely the kind of targets modern weapons which the West specializes in are optimized to destroy. Swarms of infantry with small arms scrambling over the rubble their artillery created do not invite counter-attack with expensive, sophisticated weapons. Similarly, Russian anti-aircraft firepower seems to have gained them a semblance of air dominance over the front, but that may not be able to keep up with rapidly advancing columns, thus exposing the spearheads to air attack. It is easy to imagine Western pilots in Ukrainian-marked aircraft picking of such formations. My guess is that whatever dreams the Russians may have of another Operation Bagration, they are going to keep doing what is working for them.

Interesting points for certain and from a Ukrainian perspective, this illustrates why you absolutely need strategic depth and sufficient forces to counter attack Russian attacks. Those are really challenging problems, particularly for Ukraine right now. However, one of big limitations the Russian Army suffers from (and largely always has) is their inability to sustain forces during operations, especially over a wide area during high OPTEMO periods. That creates some real opportunities, but only if you have the nerve and resources to attack that vulnerability.