In 1979, I began to investigate the origins of the tactics used by German infantry units in the great offensives of the spring of 1918. Ten years later, this effort bore fruit in the form of a book called Stormtroop Tactics: Innovation in the German Army, 1914-1918.

Stormtroop Tactics described the new way of fighting as a river with many tributaries. In particular, it traced aspects of the tactics used in the last year of the First World War to peacetime examination of reports from the battlefields of the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), the use of Pionier and Jäger units as test-beds for new methods, the work of ad hoc experimental units, the wartime efforts of ‘intrapreneurs’ of middling rank, the support provided by patrons within the senior leadership, and the phenomenon of parallel innovation. All of these phenomenon, I concluded, owed much to an organizational culture in which self-educating leaders, while differing from each other in particulars, defined the art of war as a ‘free creative activity with a scientific foundation’.1

Early in the present century, and thus more than twenty years after the start of my inquiry, I gave a talk about improvements to Stormtroop Tactics I wanted to make. This second look made use of odd bits of information picked up while looking at other things, documents I had failed to find before finishing the book, reviews and other critiques of my work, and, most especially, two books in which Martin Samuels explored British attempts to copy German ideas, institutions, and methods.2

My talk would have been much more interesting if I had recanted my original opinions. Alas, I proved unable to give my audience of the pleasure of the image of a repentant Germanophile, kneeling barefoot in the snow before the door of Paddy Griffith. (In the 1990s, Mr. Griffith wrote one book, and edited another, which presented views at odds with those that Dr. Samuels and I had expressed.)3 Rather, I remained convinced that the changes in tactics employed by German soldiers owed much to the longstanding practice of viewing tactics as a series of problems to be solved by commanders in the field.

That said, I confessed that, should I be asked to write a second edition of Stormtroop Tactics, I would have placed much more emphasis on the role played by the uniquely German institution of ‘fortress pioneers’. (In sharp contrast to the ‘fortress engineers’ of other armies, who performed duties related to the defense of fortresses, the Festungspioniere of the Prussian and Bavarian armies specialized in the art of attacking enemy fortifications.)4

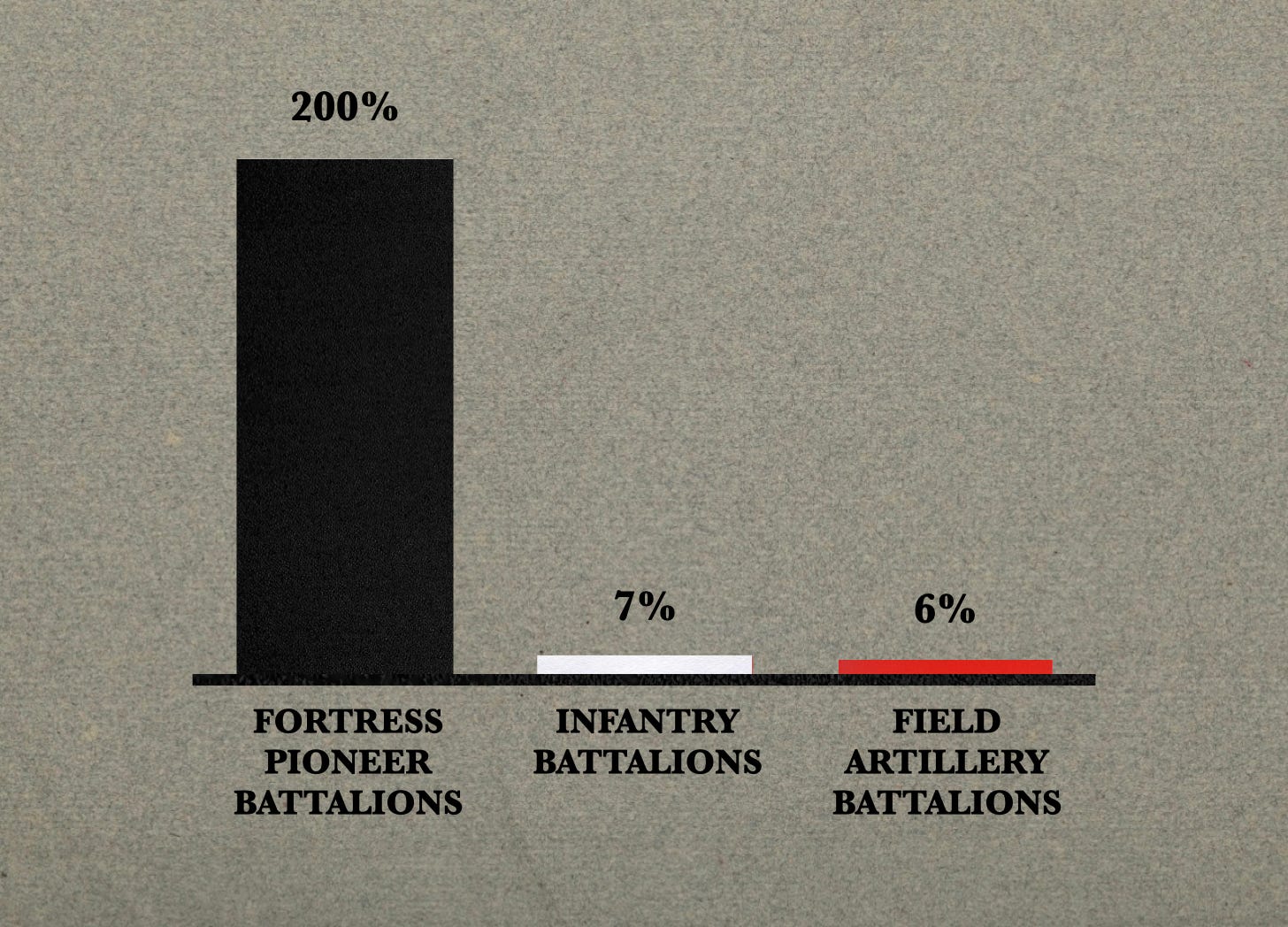

In the course of doing this, I would have mentioned that, in the years between the end of the Russo-Japanese War (1905) and the start of the First World War (1914), the number of fortress pioneer battalions serving with the peacetime armies of the German Empire grew by a factor of three. (In the same period, the number of infantry and field artillery battalions increased, respectively, by seven and six percent.)5

The improved version of Stormtroop Tactics that I outlined I would have devoted more space to the many innovations related to infantry tactics that took place within organizations other than the assault battalions (Sturmbataillone). It would thus have paid more attention to the limited objective attacks of the winter of 1914-1915, particularly those that took place in the Valley of the Aisne, the Argonne Forest, and the Vosges Mountains, as well as the work of the Musketen Battalions, the Ersatz Battalions in Germany, the Field Recruit Depots at the Front, the General Staff Course at Sedan, and various schools for officer candidates and company commanders.

A second edition of my book would also have paid much more attention to the ‘applicatory method’ (applikatorische Lehrmethode) of teaching tactics and, in particular, to such techniques as the two-sided wargame (Kriegsspiel) and the one-sided map exercise (Aufgabe).

This endeavor would be a species of intellectual history — a notoriously slippery endeavor. Moreover, while descriptions of specific exercises abound, they bear a closer resemblance to old sheet music than historical documents of the ordinary type. To make sense of them, the historian must do more than read. He must play. For only in working through such problems as if he were a student can he catch a glimmer of the tensions and dynamics at the heart of the German understanding of the art of war.

At the same time, I would have looked at the effect of the shortage of horses, and the fodder to feed them, on the ability of German infantry units on the Western Front to employ the many infantry heavy weapons, whether Minenwerfer, machine guns, or infantry guns, with which they were equipped in the last year of the war.

I knew that German authorities had taken many measures, from the centralization of field artillery ammunition columns to the ‘dismounting’ of entire divisions serving on the Eastern Front, to mitigate this problem. I also knew that infantry companies had been reduced to two vehicles - the totemic Gulaschkanone and a single wagon that carried light machine guns, grenade launchers, and reserves of ammunition. Finally, I was aware that, in those divisions that were optimized for the task of breaking through enemy positions, the number of machine guns (both light and heavy) and light trench mortars assigned to each infantry battalion had been cut in half.6

What I did not know, and, indeed, have yet to discover, is the degree to which the horse shortage limited the ability of German formations to operate. Such an investigation would have required the detailed reconstruction of attacks conducted by particular divisions and, once that was done, attempts to determine the factors - whether the exhaustion of soldiers, the failure of leaders to seize fleeting opportunities, the breakdown of discipline, or the physical inability of units to move weapons and ammunition - that had prevented the exploitation of breakthroughs.

A quick look at the catalog of the Library of Congress reminds me that the second edition of Stormtroop Tactics has remained on the proverbial drawing board for more than two decades. Indeed, the economics of academic publishing in the present century will, in all likelihood, prevent me from undertaking such a project at any point in the foreseeable future. On a happier note, the support provided by subscribers to The Tactical Notebook enables me to continue, one post at a time, a project begun a little less than half a century ago.

The phrase comes from Truppenführung, the manual for leaders of large units adopted by the German Army in the early 1930s. A translation made for the U.S. Army in 1936 renders the sentence as ‘The conduct of war is an art, depending upon free creative activity, scientifically grounded.’ The original manual can be found in the collections of the U.S. National Archives and Record Service, Records of the Army High Command, Microfilm Series T-78, Roll 201. (Alas, I have not been able to find a copy of this reel that has been digitized, let alone placed online.) The aforementioned American translation – Truppen Führung (Troop Leading) (Fort Leavenworth: The Command and General Staff School Press, 1936) – hangs its hat on the website of the Combined Arms Research Library.

Martin Samuels Doctrine or Dogma? German and British Infantry Tactics in the First World War (New York: Greenwood, 1992) and Command or Control? Command, Training, and Tactics in the British and German Armies, 1888-1918 (London: Frank Cass, 1995) (For a list of the books and articles written by Dr. Samuels, see his page on Academia.edu.)

Paddy Griffith Battle Tactics of the Western Front: The British Army’s Art of Attack: 1916-1918 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994) and Paddy Griffith, editor British Fighting Methods in the Great War (London: Frank Cass, 1996) (Reasonably priced copies of the former can be found on the website of Thrift Books.)

Much information about German fortress pioneer units can be found in Paul Heinrici, editor Das Ehrenbuch der Deutschen Pioniere (Berlin: Verlag Wilhelm Kolk, 1932) pages 32-41 and 54-8. (This work has yet to pass into the public domain. However, Patrick Schallert, of Military Books 14-18 will, for a modest fee, provide you with a high quality scan of his copy.)

Figures for the number of battalions of various kinds serving with the peacetime armies of the German Empire come from the issues of Loebells Jahresberichte (Loebell’s Annual Reports) published between 1905 and 1913. (Both Hathi Trust and the Internet Archive catalog issues of this indispensable compendium under the name of its short-lived successor, Rüstung und Abrüstung (Armament and Disarmament). The names of the units concerned and the precise dates of their establishment can be found in Eike Mohr Heeres-und Truppengeschichte des Deutschen Reiches und Seiner Länder 1806 bis 1918 (Army and Unit Histories of the German Empire and its States, 1806 to 1918) (Osnabrück: Biblioverlag, 1989).

Franz Uhle-Wettler Erich Ludendorff in Seiner Zeit (Erich Ludendorff in his Times) (Berg: Kurt Vowinckel Verlag, 1996) page 319; Hermann Cron, Geschichte des Deutschen Heeres im Weltkrieg 1914-1918 (History of the German Army in the World War, 1914-1918) (Berlin: Karl Sigismund, 1937) page 151; Ernst Otto Sternenbanner gegen Schwartz-Weis-Rot (Star-Spangled Banner against the Black-White-Red Flag) (Berlin: Verlag Tradition Wilhelm Kolk, 1930) pages 27-8; and Theodor Spieß Minenwerfer im Großkampf (Trench Mortars in Great Battles) (Munich: I.F. Lehmanns Verlag, 1933)