Part IV

15.) The Division as an Counterattack Reserve.

In the sector of Army Group Center the division was kept in readiness for service as an counterattack reserve [Eingreifreserve]. Contingency plans were researched, discussed, and wargamed on the map [in Planübungen durchgespielt]. In almost all cases, higher headquarters designated the proposed contingencies. The chief success of this work was that the units learned the terrain.

Because the interaction of the enemy and the terrain created different conditions than those which prevailed during our reconnaissances, our actual engagements were entirely different from our plans. Nonetheless, the orders for the employment of the division were based upon the results of the reconnaissances.

The most important lesson that the division took away was that it was impractical to make a frontal counter-attack against an attacking enemy as well provided with artillery and heavy weapons as the one at Rshev on the 10th of September 1942. In this case, a flank attack was not possible.

Thus, part of the division had to be sent into the front lines where other German troops were still holding out, there to parry the blow. The actual attack of the division, which required careful preparations, could only be made once the enemy had been halted.

On the 9th of September 1942, units were held in readiness 1,500 meters behind the front lines. Once the attack began, they took such losses negotiating these 1,500 meters, part of which was under enemy observation, that the attack proper was only able to capture a little ground. 1

It seems practical, whenever it is certain that the division will soon go into action, to locate the units, at the very least the infantry, far enough forward so that they can go into action on foot.

If, on the other hand, the division must hold itself in readiness to counterattack in the sectors of a number of divisions, it is better to locate it in the middle distance behind the front. In this regard, ten to twenty kilometers of road plays no role for a motorized unit, because the approach march and dismounting is more easily accomplished when the units are sent forward at intervals.

Example:

At Rshev the forward elements [of the division] lay some ten kilometers behind the front. The division was then ordered to move closer to the front. This required the division to leave the main highway and move into the small woods away from the main highway.

When suddenly ordered to get moving, the whole division could not fit on the road. It took six or eight hours for the fighting elements of the division to get moving.

The feeder roads to the highway were particularly bad. There were lots of traffic jams. The “highway” [Rollbahn] turned into a “stopway” [Stehbahn] and offered the enemy air force a welcoming target. All of this could have been avoided if the division had been arrayed close to a 20 to 30 kilometer length of the highway and, as a result, a quick traffic flow had been made possible.

In addition, quickly sending forward parts of the division behind sectors of the front in response to reports of enemy activity. These movements can be very reassuring, when a battalion stands behind a threatened sector of the front. It can, however, particularly in winter, wear out a unit with marching. In the case of a motorized unit, this is not a matter of kilometers.

For example. A battalion on the alert in quarters, with vehicles protected from the cold weather, can be quickly started up. The unit can thus get on the road quickly. This battalion will sooner arrive at the objective than a battalion which is perhaps 20 kilometers closer to the endangered position. The latter must must have its men bivouac. It will lack shelter for its vehicles and these, as a result, will be slow to get going.

Night Marches

Motorized night marches on Russian roads are, particularly for tracked vehicles, very difficult, often senseless. The time gained by a night march is lost through the exhaustion of the unit. The loss of vehicles is heavy, the consumption of motor fuel is doubled. Also the losses due to bombs dropped from slow-flying Russian planes (the so-called “coffee grinders”) are to be taken into account. As these planes often drop parachute flares, the concealment which we hoped to gain by the night march is often lost.

In the approach march for the southern campaign, having the wheeled vehicles march at night while the tracked vehicles marched by day proved itself practical. The tracked vehicles, covered with foliage for camouflage, moved with large intervals between them.

A proper understanding of the principles of employing large motorized units in not present to the required degree in many army corps. Perhaps during the training of future general staff officers, more emphasis might be placed on their gaining an understanding of the armored troops.

16.) Battle Leadership during Counterattacks, with Particular Emphasis on Combatting Enemy Heavy Weapons.

In the sector of Army Group Center enemy artillery and, above all, mortars (which seemed to make use of a great number of shells: over 1,000 shots for each tube) were responsible for heavy losses. Often counter thrusts were pinned-down by fire if the infantry was not able to run under the fire, which, due to snow, winter clothing, and the exhaustion of the troops was no longer possible. Time and again the following was said to the division: “Find a means to suppress the heavy weapons of the enemy.”

On the basis of successful attacks, the division arrived at the following solution.

a.) A prerequisite to the suppression of heavy weapons is knowledge of their location. This is only possible through continuous and painstaking observation, supplemented by aerial photos.

b.) Once targets are clearly known, they must be subjected to “point fire” [Punktfeuer] either before or during the beginning of the attack. For example, mortars which are located on a forward slope (where they are least expected) are to be combatted. Because of masterful camouflage, these can only be made out by accident.

The artillery should get involved in this process. This does not violate the principle of “not shooting artillery just for fun.” In modern war, particularly against the Russian enemy, one sees so little of the enemy that it is worth our while to fire many tubes against a single machine gun. The knocking out of a machine gun is far more important for our infantry than the twenty teamsters [Troßknechte] killed by harassing fire in the rear areas.

c.) For the attack itself, an exact fire plan must be made, a procedure that motorized troops are rarely practice. Insofar as the question of the timing of attacks are concerned, attacking at dawn has shown itself to be no longer practical. The Air Force is often not available at that hour and the enemy is awake. In attacks towards the east, moreover, the light is not favorable.

On the 19th and 30th of September, the division carried out two successful attacks in the afternoon. The timing was arranged in a manner that allowed the objective [Angriffsziel] to be reached, the terrain organized, and contact made with neighboring units before dawn. The enemy was, as a result, no longer able to establish where our attacking points [Angriffsspitzen] lay and register his heavy weapons upon them.

d.) During both attacks, the success was the result of surprise. Surprise was secured because there was no preparatory fire and because the attacking assault squads [Angriffsstosstrupps] had, the night before, entrenched themselves forward [of the German front lines.]

e.) In the fire plan it was established, who shot at what and who blinded [with smoke] what. With the first fire strike [Feuerschlag], artillery and infantry heavy weapon shells fell upon the previously established targets. A special artillery group began immediately to blind [with smoke] specific bits of ground where observation posts and anti-tank guns were suspected.

The bulk of the aircraft hit the artillery positions and “Stalin Organs” right behind the enemy main line of resistance [Hauptkampflinie.] Attack aircraft suppressed artillery further back. The infantry attacked with the first Stuka bomb, which also signaled the beginning of the fire strike [Feuerschlag.]

f.) After the first fire strike (duration five to ten minutes), the infantry regiments used their heavy weapons and the artillery battalion assigned to work with each of them to combat targets that popped up in the depth of the enemy defensive position. The rest of the artillery was in the hands of the [divisional] artillery commander and used for fire concentrations [Feuerschwerpunkte.]

As long as the Air Force flew over the battlefield, enemy fire was generally held back. It was therefore agreed upon that the aircraft would continue flying over the enemy positions for a few minutes after they had dropped their last bombs. Stukas would use their sirens [Jerichogerät] and fly back and forth over the enemy position.

Counter-battery work only makes sense if we are sure of the target and our own artillery is strong. When our own artillery is weak, counter-battery fire during (not before) the attack splits up our artillery and bears little fruit. The entire fire, including that of heavy batteries, ought to be controlled by forward observers [vorgeschobene Beobachter] and belongs right in front of the infantry. In this way, the enemy artillery is often deprived of its observation, which does far more damage than the loss of a single gun.

g.) In both of the aforementioned cases, the enemy attempted a counterattack in battalion strength. This is the time that assault guns and tanks can give support to the infantry and the eyes of the artillerymen must be directed far forward.

In these cases, it proved practical to request a second Air Force mission and to use the forward air controller [Stukaleitoffizier] to call dive bombers out of the sky. In all cases one call also give secondary targets [to the aircraft.]

h.) When the enemy artillery was very strong, it proved more practical to have a few machines continuously in the sky than to have two squadron missions with a two or three hour pause between them.

17.) Counter-Attack Reserves

Time and again, particularly in the defense, the formation of counter-attack reserves [Eingreifreserven] and boundary reserves [Nahtreserven] has proved itself practical, even these consisted only of a few squads. Needless to say, only good squad leaders could lead these squads. These were kept close behind the command posts or the boundaries between units. Possibilities of employment and the ground must be well known to the counter-attack reserve units. The division ought, if possible, to make use of a reinforced battalion as a attack reserve.

Source: This is a verbatim translation of an after action report submitted by the operations officer (Ia) of the Infantry Division Großdeutschland. A typescript of the original German report can be found in the records of the Tank Officer with the Chief General Staff of the Army [Panzer Offizier beim Chef General Stabs des Heeres.], U.S. National Archives, Microfilm Series T-78, Roll 620, Frames 923-945. Words in italic type were underlined in the original document.

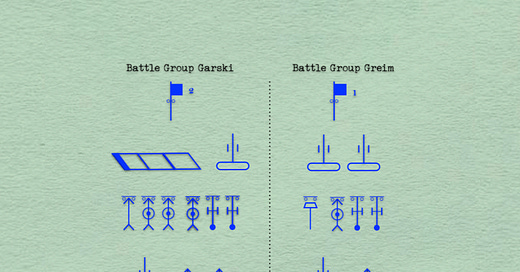

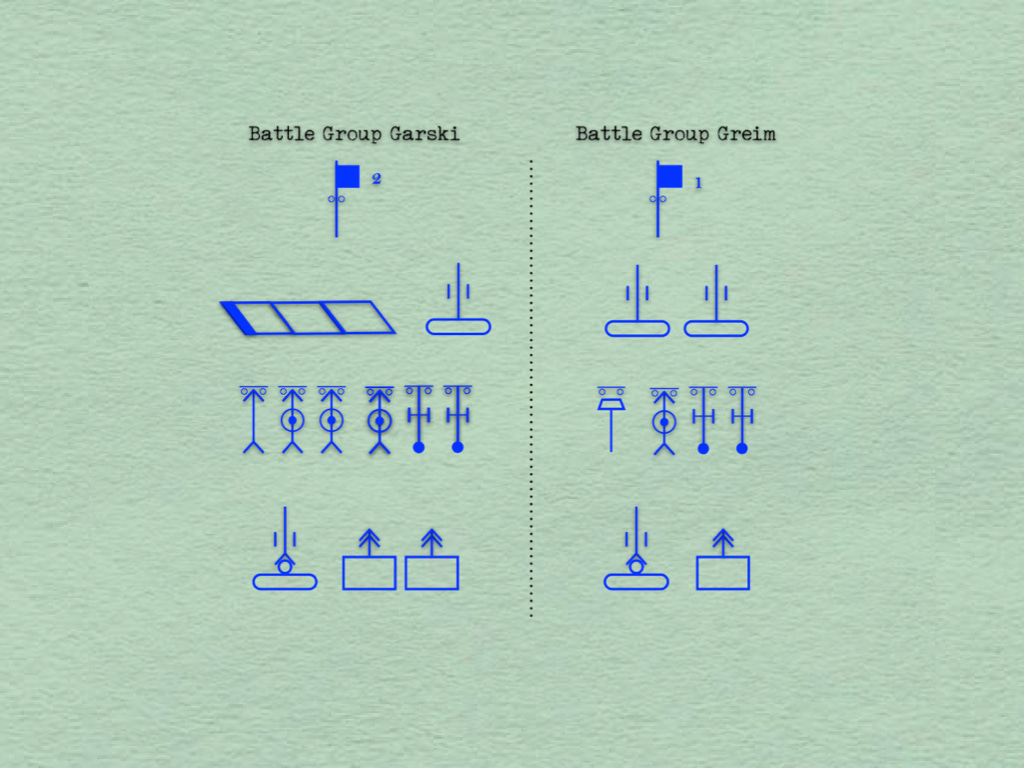

The diagram shows the two battlegroups organized on 9 September 1942. (A third or so of Battle Group Greim, to include an infantry battalion and a battery of 105mm gun-howitzers, was designated as the division reserve.) T-315 Roll 2283 Frames 685-687