Of the many French trench mortars to see service during the winter of 1914-1915, the one with the greatest staying power was the one invented by Émile Auguste Duchêne (1869-1946.) An officer of engineers (and graduate of the famous École Polytechnique), Major Duchêne had long been fascinated by the effect of empennages (small, fixed wings) upon objects in flight.1

Soon after the outbreak of war in 1914, Duchêne, who was serving at the front as the senior engineer officer of the 70th Infantry Division, began to experiment with spigot mortars.2 The first weapon to result from this work consisted of a wooden rod that fired projectiles made out of the brass propellant cases of field gun rounds. As the flat-nosed propellant cases sometimes flew erratically, Duchêne provided them with fins made out of zinc .

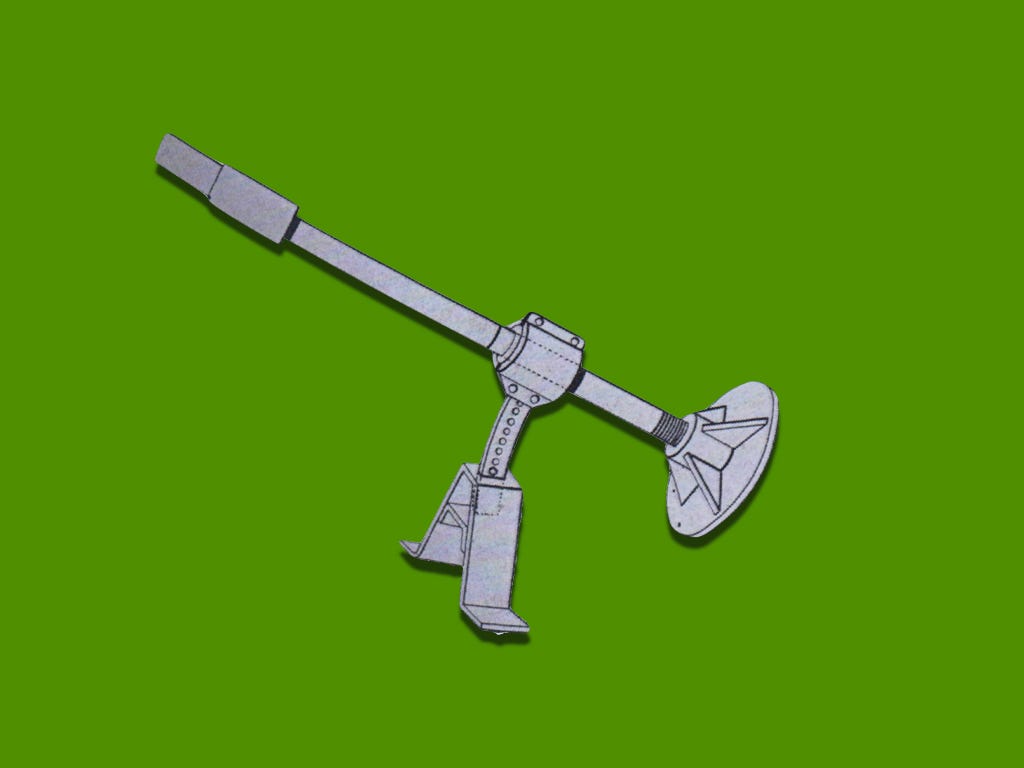

Upon learning of these experiments, General Joseph Joffre transferred Duchêne to the Central School of Pyrotechnics at Bourges. There, he replaced the wooden rod with one made out of steel, which he provided with a bipod, a base, and a means of adjusting elevation. At the same time, he replaced the projectiles made out of brass propellant cases with winged bombs, each of which was made of steel and loaded with six kilograms of high explosive.

The new weapon, which was variously known as the “Duchêne device” [appareil Duchêne] and the 58 T, made use of components that Duchêne found at a nearby arsenal. (The 58mm steel tubes that gave the mortar its numerical designation came from the recoil mechanisms of 105mm heavy guns that the arsenal had begun to make, but never completed. The cylinders that became the bodies of the first batch of projectiles came from experimental steel shells that had been built to be fired from Louis Philippe mortars. The perchlorate of ammonia that filled the shells was an explosive that, while widely used for civilian purposes, had proved too unstable for use in shells fired by guns or howitzers.)

Thanks to the availability of these pre-existing elements, Duchêne needed less than two months to build a number of fully functional prototypes of his new weapon. Once they were ready to make their debut at the front, Duchêne took several of these weapons to the Argonne, a region of heavily forested hills that had been especially congenial to the employment of Minenwerfer. After putting this first batch of mortars through their paces in the front line, Major Duchêne returned to Bourges to make the improvements that would make his invention more stable, more portable, and capable of firing larger bombs.3

For Further Reading:

To Support, Subscribe, or Share:

See, for example, his article about the role such empennages might play in the design of airplanes: “Duchêne, “Au sujet de l’emploi des empennages porteurs dans la construction des l’aeroplane” Revue de Génie Militaire Tome XXXXIV (Second Semester 1912) pages 546-548

On 22 November 1914, Major Duchêne took command of the engineer companies of recently formed 33rd Army Corps. 33e Corps d’Armée (Génie), Journal des Marches et des Opérations, 6 octobre 1914-2 juin 1915 et 15 mars-3 mai 1916, Archives de Guerre, 26 N 215/14

Pierre Waline, Les Crapouillots, 914-1918, Naissance, Vie, et Mort D’Une Arme (Paris: Charles-Lavauzelle, 1965) pages 45 to 52