In the mobile campaigning of the first three months of the First World War, the French field artillery, armed mostly the M1897 75mm quick-firing field gun, had done well. Towards the end of this phase of fighting, when the overextended Germans were trying to attack the French defensive positions along the Marne, the “French 75” made good use of its ability to fire high explosive shells at ranges beyond those attainable by German field guns.

Once trench warfare started, however, the French field artillery proved powerless in the face of German field fortifications. Even when supplied with high explosive shells, which were increasingly hard to find, the 75mm field gun could neither collapse trenches nor clear paths in barbed wire obstacles.

The first official French attempt to solve this problem involved the use of small wagons filled with explosives. Guided across “no man’s land” by means of poles and wires, these primitive precursors of the unmanned ground vehicles invariably foundered in ruts or mud.

French attempts to cut wire with sustained machine gun fire also failed to achieve success. While a few thousand rifle-caliber bullets could certainly eat away at the wooden or even metal stakes that supported strands of wire, it would have taken hundreds of thousands of rounds to carve a single, very predictable lane through the kinds of barbed wire entanglements that had became common by the end of the winter of 1914-1915.

While the French experimented with these methods, the Germans were making extensive use of trench mortars. Initially designed for attacks against permanent fortifications, these Minenwerfer (“mine-throwers”) quickly proved themselves capable, not only of tearing gaps in barbed wire obstacles, but also of churning up the ground that provided shelter to infantrymen.

The key to the success of the Minenwerfer was the use of high angle fire. This allowed the trench mortar to use a comparably small propellant charge to lob a comparably large bursting charge for a few hundred meters. It also allowed the trench mortar to fire from a fully defiladed position, whether a trench, a hollow, or the proverbial “other side of the hill.”

Impressed by the success of the Minenwerfer, French soldiers began looking for trench mortars of their own. They found an immediate, if far from ideal, solution in storage depots, fortresses, and, if we can believe the legends, museums. This was a muzzle-loading smoothbore mortar that had been designed during the reign of King Louis Philippe (1830-1848) to fire spherical shells over the walls of fortresses. When provided with bags of pre-measured propellant and improvised projectiles of various types, these bronze-and-wood weapons, some of which had served in the siege of Sevastopol (1854-1855), provided some means, however imperfect, of responding in kind to the fire of Minenwerfer.

The most common of the payloads delivered by the Louis Philippe mortars included the cast iron spheres that they had been originally designed to fire, baskets filled with grenades, and tin cylinders filled with cheddite. The first of these might be filled with either black powder or a more up-to-date explosive. The second carried thirteen sub-munitions. The third, known as bombes Nicole, were provided with a Bickford fuze (a piece of impregnated cord lit by the act of firing).

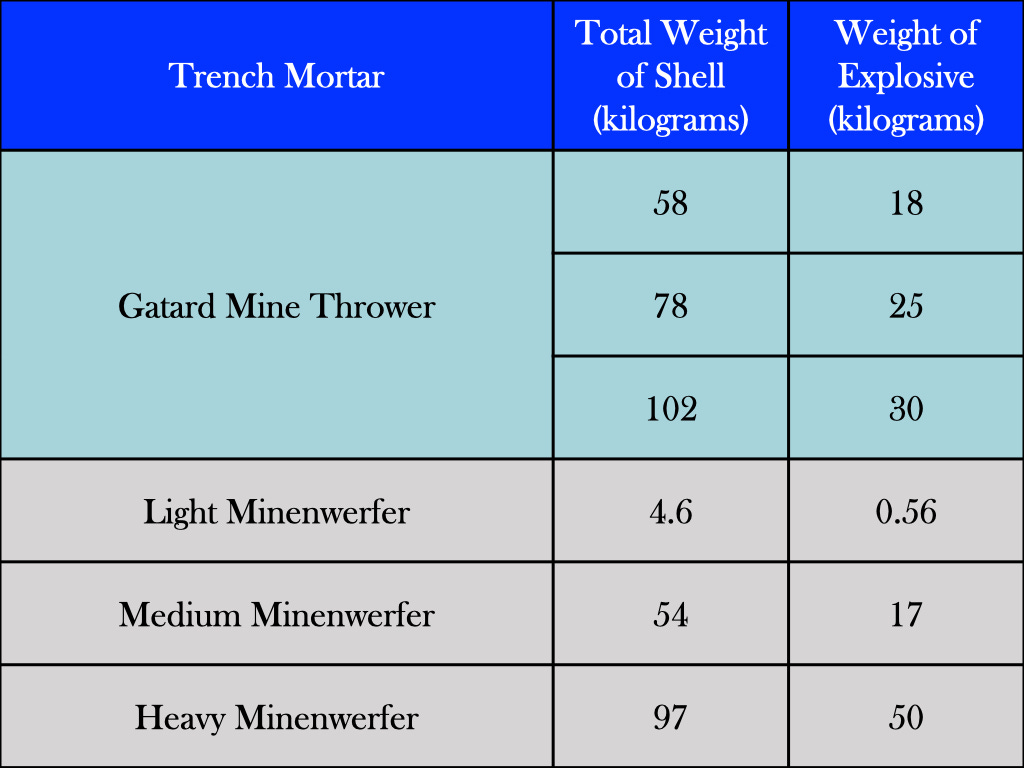

To fire projectiles heavier than those tossed by the aforementioned antiques, a French inventor converted 80mm mountain guns (Model 1878) of the De Bange system into spigot mortars. The resulting lance-mines [“mine-thrower”] Gatard fired a variety of bombs, each of which was mounted on a rod that fit into the barrel of the piece.1

Because the size of the barrel was no longer a limiting factor, the lance-mines Gatard could be provided with projectiles of various sizes. Indeed, while the inventor designed three standard projectiles for his device, the only reason to avoid improvising others was the need to compose new firing tables.

The barrel (or, more precisely, the spigot) of the lance-mines Gatard was permanently fixed at an angle of thirty-five degrees. Thus, in order to adjust the distance he wished his projectile to travel, the gunner had to change the amount of propellant in the chamber. (The authors of the firing tables for this device were so confident in the ability of gunners to measure propellant that they provided a specific weight of power for every five meters of range.)

Another French inventor, Captain Jean-Fernand Cellerier, built a trench mortar that was, at once, more ingenious than the lance-mines Gatard and even simpler than the repurposed Louis-Philippe. The process of design began when the inventor noted that the brass propellant cases for rounds fired by French 65mm mountain guns fit perfectly into the steel bodies of spent German 77mm shrapnel shells. Mounted on a block of wood, the resulting weapon could fire a cylindrical bomb weighing 1.8 kilograms as far as 300 meters.

The original mortier Cellerier inspired the building of similar devices out of the bodies of shrapnel shells fired by French 75mm guns and German 105mm guns. In the absence of the serendipitous synchronization of the interiors of these shell bodies and the propellant cases of other weapons, the latter mortars fired smaller versions of the bombes Nicole.

Sources:

Pierre Waline Les Crapouillots, 1914-1918, Naissance, Vie, et Mort d’une Arme (Paris: Charles-Lavauzelle, 1978), Chapters II and III

Polster “Minen-und Bombenwerfer Frankreichs” Kriegstechnische Zeitschrift (1917) pages 153-156

For Further Reading:

To Share, Subscribe, or Support:

The inventor of the lance-mines Gatard was Gaston Thomas François Gatard (1872-1941), a French naval engineer who, during the first two years of the war, served at the front with the Régiment de Canonniers Marins.