This article forms part of a multi-stage series. To read the preceding portions, please follow the following links:

At the start of the Napoleonic Wars, each of the component artillery companies of the British Army rated a particular number of officers, non-commissioned officers, and gunners. At the same time, they often changed their armament, mode of employment and means of transport. In the course of the long struggle against France, troops of horse artillery received fixed allowances of ordnance, vehicles, and quadrupeds. Nonetheless, other units of the Royal Artillery continued to equip themselves on an ad hoc basis.

In the middle years of the nineteenth century, the artillery companies configured as field batteries, that is, with relatively light ordnance and sufficient transport to keep up with the other elements of an army on campaign, tended to remain in that role for long periods of time. Thus, by the end of 1861, the Royal Artillery had gathered these ‘field batteries’ into separate ‘brigades’ and established specialized recruit depots. Thus, while a fledgeling gunner destined for a garrison company studied subjects of value to sedentary soldiers, his counterpart at a training center for future field artillerymen devoted a lot of time and trouble to the care, feeding, and housing of horses.

During the Second Afghan War (1878-1880) the Royal Artillery formed mountain and heavy batteries. (Armed with pieces that heavier than those issued to field batteries, the latter could, with the aid of horses, oxen, or elephants, move from place to place without resort to shuttling.) Towards the end of the following decade, a Europe-wide revival of interest in siegecraft led to the conversion of selected garrison companies into specialized siege artillery units.1

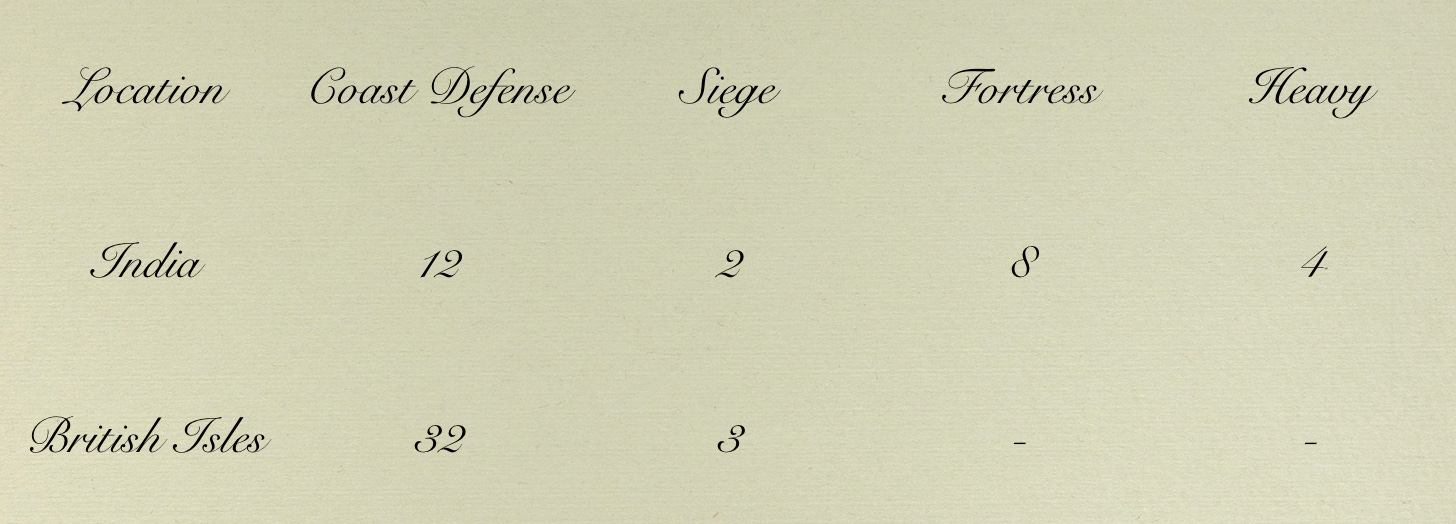

The distribution of specialized artillery units correlated with the peculiar needs of particular places. Thus, in 1899, all four heavy batteries and all eight fortress artillery companies occupied stations within the borders of the Indian Empire. In the same year, however, only twelve of the eighty coast defense companies guarded the ports and harbors of the Subcontinent.

The lopsided distribution of specialized units complicated the periodic ‘relief’ of units that had been located overseas for several years with counterparts that had recently enjoyed a substantial spell of service within the British Isles. In particular, a unit sent out from the United Kingdom in 1899, had, in all likelihood, been configured as a coast defense company. When, however, it arrived in India, it stood an even chance (twelve out of twenty four) of transformation into an organization of a purely terrestrial character.2

Units moving from one corner of the world to another lost a lot in the way of local expertise. When, moreover, they compounded the cognitive costs of relocation with the need to trade one set of technical skills for another, the sacrifice of savoir-faire could be considerable. At the same time, the more senior members of a company involved in a relief enjoyed an expansion of their professional horizons.3 This polyvalence of perspective, in turn, made the Royal Garrison Artillery a more flexible instrument of strategy than might otherwise have been the case.

Callwell and Headlam The History of the Royal Artillery, Volume I (1860-1899) pages 11, 78-79, and 271-82

Details of reliefs can be found in back numbers of the (privately published) Army and Navy Gazette and the semi-annual compilations of Army Orders published by the War Office. The assignments of various garrison companies at any given point in time can be found in the Monthly Army List.

I propose, for the position of paragon of polyvalent projectile placement, Charles Edward Callwell.