Had it ever been assembled in one place, the heavy ordnance available to the British Army at the start of World War I would have formed a collection of considerable diversity. Alongside a handful of pieces of types fielded by contemporary armies, this imperial artillery park would have included a large number of weapons that, while familiar to a student of contemporary naval armament, might have seemed somewhat out of place in a purely military arsenal. Likewise, while it would featured some recent products of the gun founder’s art, it would also include a great deal of Edwardian ironmongery and, marvelous to say, a handful of muzzle-loading guns and howitzers.

The maritime flavor of so much British ordnance owed much to the role played by the British Army in coast defense. Where the heavy artillery branch of the German Army (Fußartillerie) focused most of its attention to war on land and that of the French Army (artillerie à pied) divided its attention between two elements, the Royal Garrison Artillery served, first and foremost, as a means of defending the harbors, rivers, and ports of the British Empire against attack by hostile fleets. All other responsibilities – whether the creation of siege trains, the defense of fortresses on land, or the provision of mobile heavy artillery to armies in the field – played second fiddle to this task.1

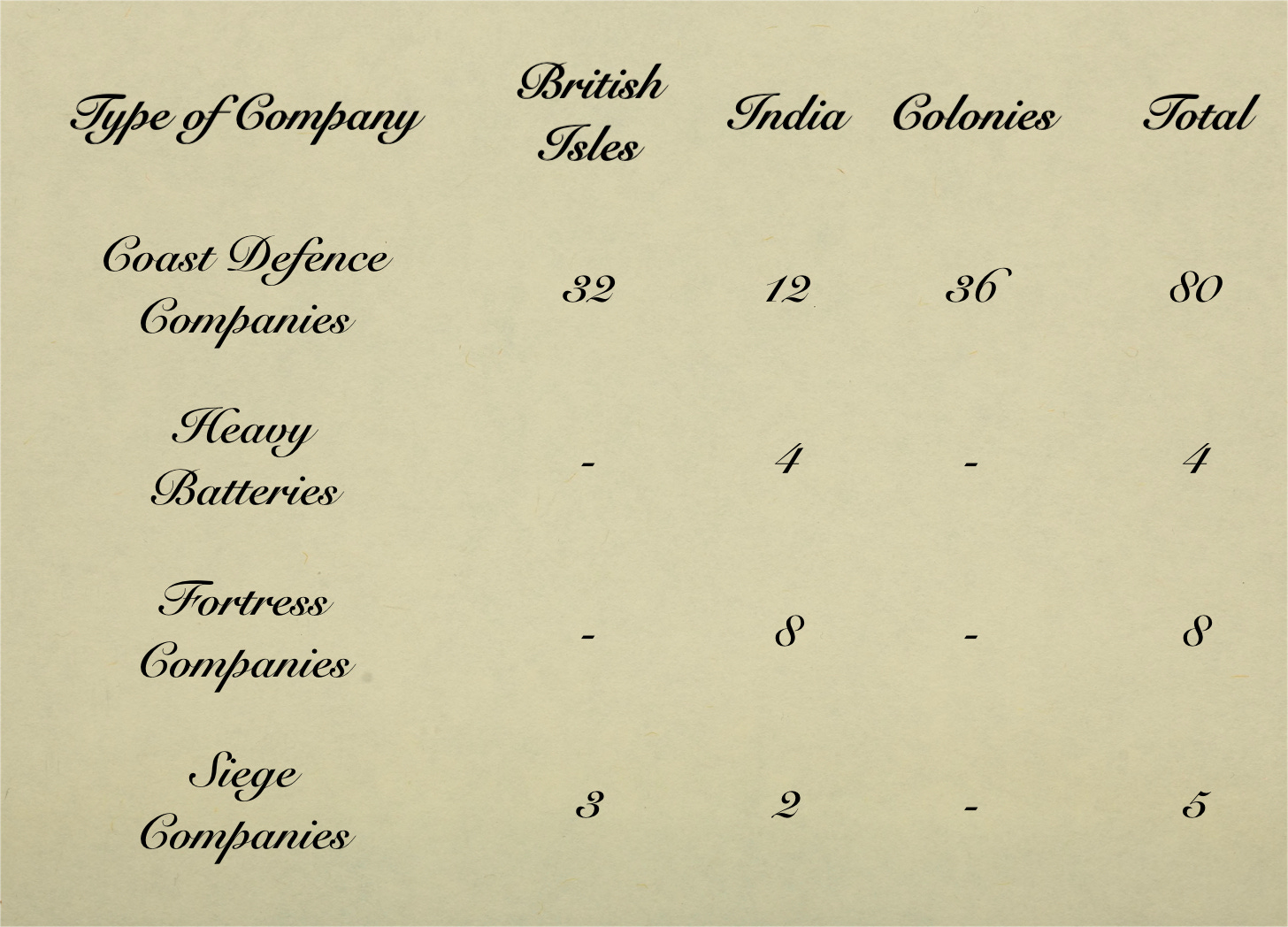

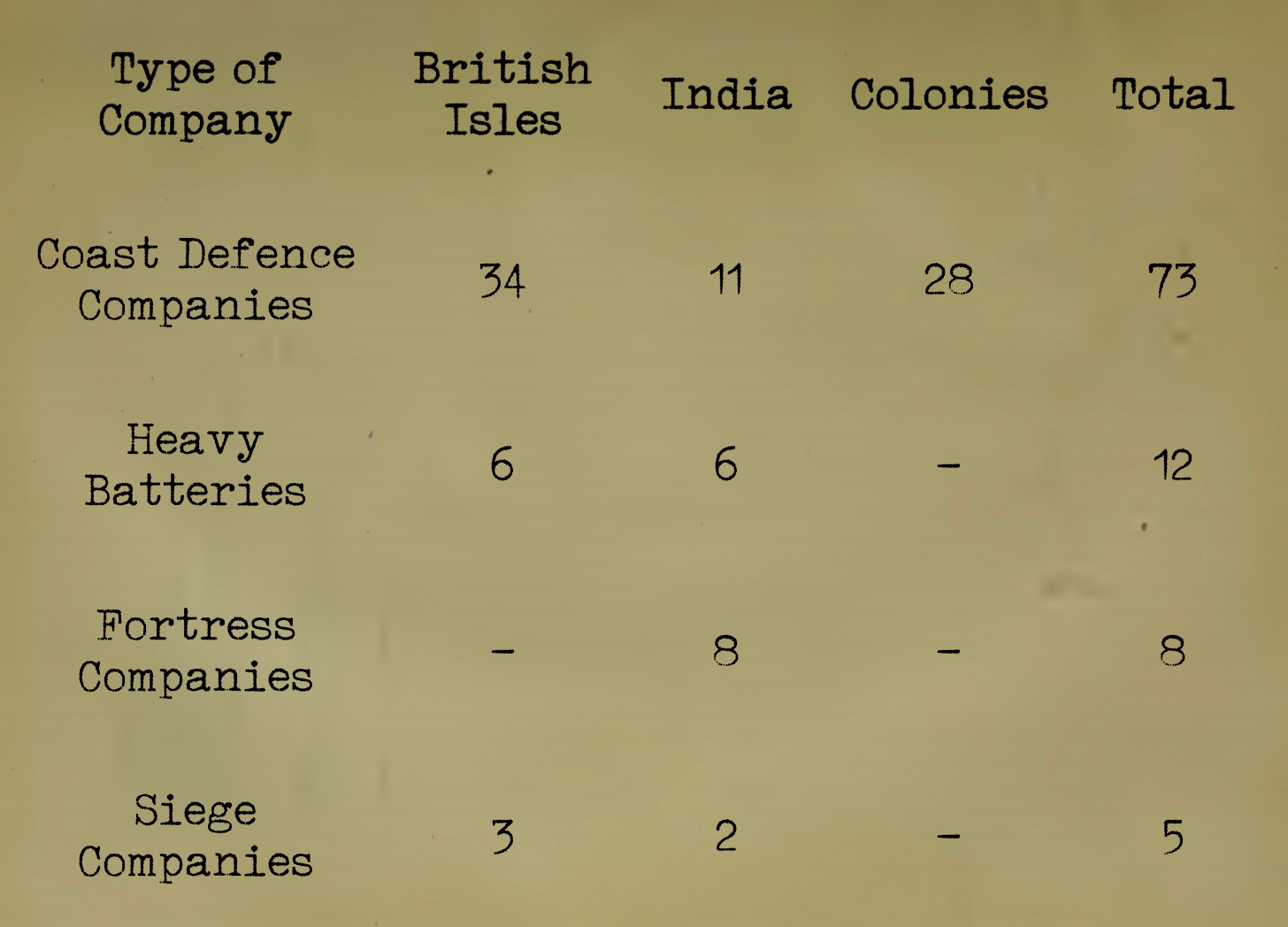

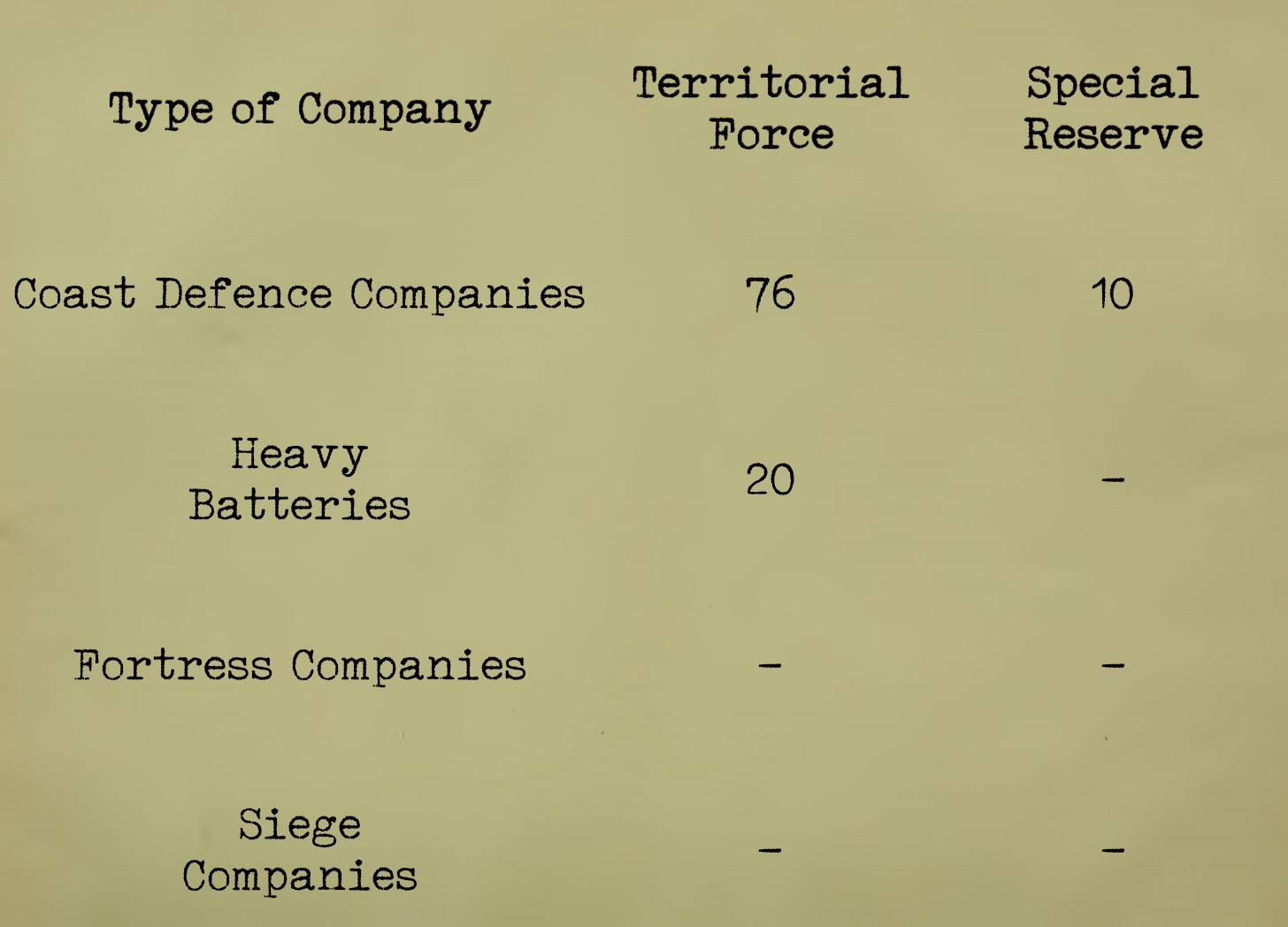

In keeping with its institutional emphasis on coast defense, the Royal Garrison Artillery configured the vast majority of its organizational building blocks (known as ‘service companies’, ‘garrison companies’ or ‘garrison artillery companies’) as coast defense units.2 In an accounting dated 1 June 1899, eighty of the ninety-seven of the component companies of the Royal Garrison Artillery had been configured as coast defense companies.3 In the course of the fifteen years that followed, the ratio of coast defense companies to companies of other sorts dropped from close to five to one to a little less than three to one.4 Nonetheless, the number of coast defense companies in the Royal Garrison Artillery continued to exceed the number of garrison companies of other kinds by a very comfortable margin. Because of this, a man who made a career of service in the Royal Garrison Artillery could count upon spending more time defending the maritime choke points of the British Empire than performing duties related to the defense of fortresses on land, the capture of fortresses in hostile hands, or the handling of the especially heavy ordnance of armies in the field.5

Mountain batteries formed an autonomous division within the Royal Garrison Artillery. As a result, they often appear in lists of units belonging to that branch. However, as mountain batteries exercised little influence upon the development of British heavy artillery, I have left them out of the various lists and calculations presented in this series.

As used in this series, the term ‘Colonies’ encompasses all stations, including those located in the Channel Islands and the self-governing dominions, other than those on the territory of the United Kingdom or the Empire of India.

When configured to take the field, a company of the Royal Garrison Artillery bore the designation of ‘battery’. When, however, it served in a sedentary role, it retained the title of ‘company’. Thus, the units that defended fortresses on land were known as ‘fortress companies’. In time of peace, siege companies lacked organic transport. When, however, they mobilized for war, they transformed themselves into siege batteries. (A siege company serving in India would transform itself into a single siege battery. One serving elsewhere, however, would split into two siege batteries.)

The figures used in the three tables come from Sir John Emerson Wharton Headlam The History of the Royal Artillery from the Indian Mutiny to the Great War: Volume II (1899-1914) (Woolwich: Royal Artillery Institution, 1931), Appendix E and War Office Peace Establishments for 1914-1915, Part I (Regular Forces and Special Reserve) (London: HMSO, 1914) page 60 (Note: While General Callwell and General Headlam collaborated on the first volume of their history of the Royal Artillery, the latter served as the sole author of the second volume.)

The Royal Garrison Artillery owed its separate existence to a Royal Warrant that, in June 1899, split the Royal Regiment of Artillery into two separate corps. (The other corps, sometimes called the ‘mounted branch,’ consisted of the Royal Horse Artillery and Royal Field Artillery.) From the point of view of both organizational culture and career progression, however, the separation between the sedentary, scientific gunners of garrison units and the mobile, horsey gunners of mounted batteries had been in force for nearly half a century. Charles Edward Callwell and Sir John Emerson Wharton Headlam The History of the Royal Artillery from the Indian Mutiny to the Great War: Volume I (1860-1899) (Woolwich: Royal Artillery Institution, 1931) pages 2-3, 86-88, 104-5, 130-31, and 331-32.

“Had it ever been assembled in one place, the heavy ordnance available to the British Army at the start of World War I would have formed a collection of considerable diversity.” How very polite you are this morning!

More seriously, this illustrates the difficulties of updating already in service arsenals during times of industrial innovation and low threat. Other than the Boer War, which did spur quite a bit of innovation and development, albeit mostly for the other artillery branches, and perhaps the Boxer Rebellion, the British Army had not faced a near competitor since Crimean War (unless I missed one).