William Balck on Field Artillery (V)

Armies of the First World War

This is the fifth (and last) part of a five-part article. For the first four parts, see Balck on Field Artillery (I), Balck on Field Artillery (II), Balck on Field Artillery (III), and Balck on Field Artillery (IV).

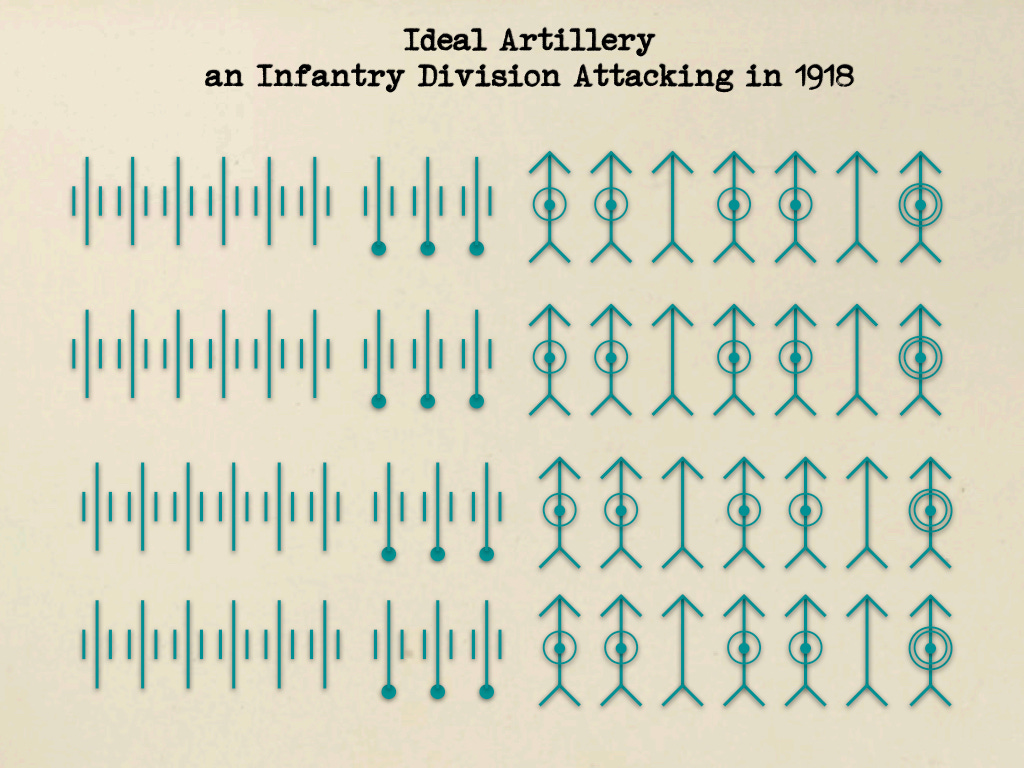

Major General William Balck concluded his article by describing the ideal allocation of guns and howitzers to an infantry division taking part in one of the German offensives that took place in the spring of 1918.

After doing a number of calculations, Balck concluded that, in order to conduct a successful attack on a front with a width of two kilometers, an infantry division needed a grand total of sixty-four batteries.1 Of these, four would be armed with 21cm heavier howitzers, sixteen with 15cm heavy field howitzers, eight with 10cm guns, twelve with 10.5cm light field howitzers, and twenty-four with 7.7 cm light field guns.2

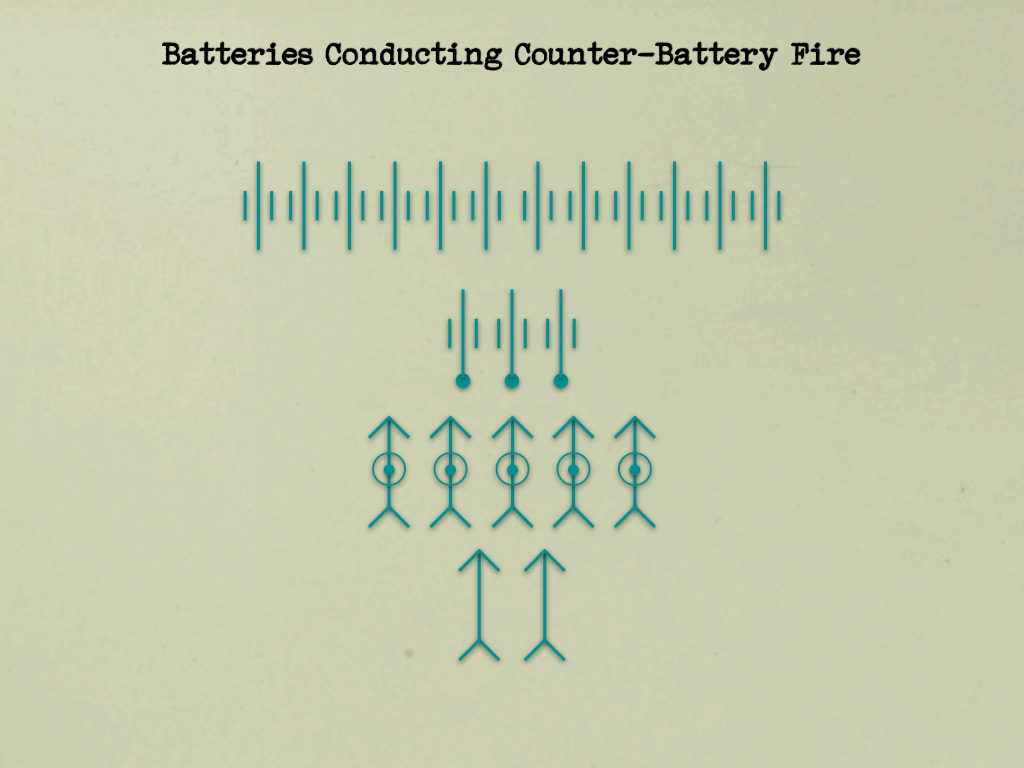

Of the sixty-four batteries of the ideal artillery park of an infantry division attacking in 1918, a little more than a third were charged with suppressing the fire of enemy artillery pieces. The twelve field gun batteries did this by creating and maintaining a cloud of poison gas over the area occupied by hostile artillery units, the other ten counter-battery batteries fired high explosive shells at battery positions and ammunition dumps.

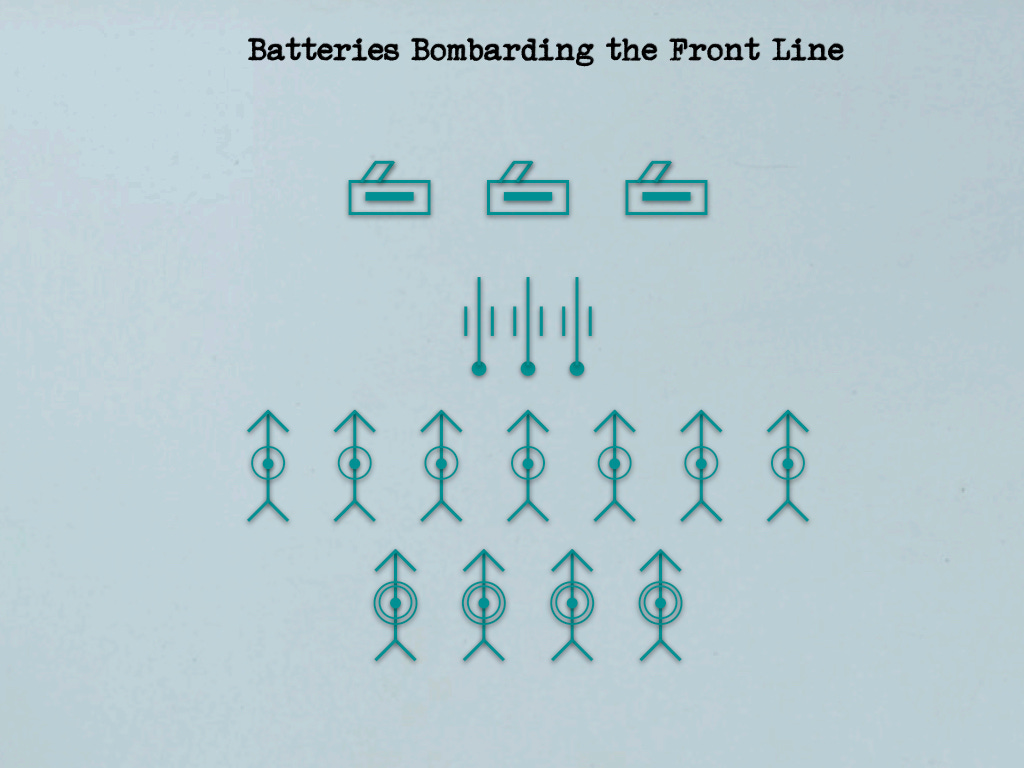

Somewhat less than a quarter of the total number of batteries given the task of bombarding the forward positions occupied by enemy infantry. These fourteen batteries, all of which were equipped with howitzers of one sort or another, received considerable assistance from three Minenwerfer companies, each of which operated four heavy (250mm) and eight medium (17cm) trench mortars.

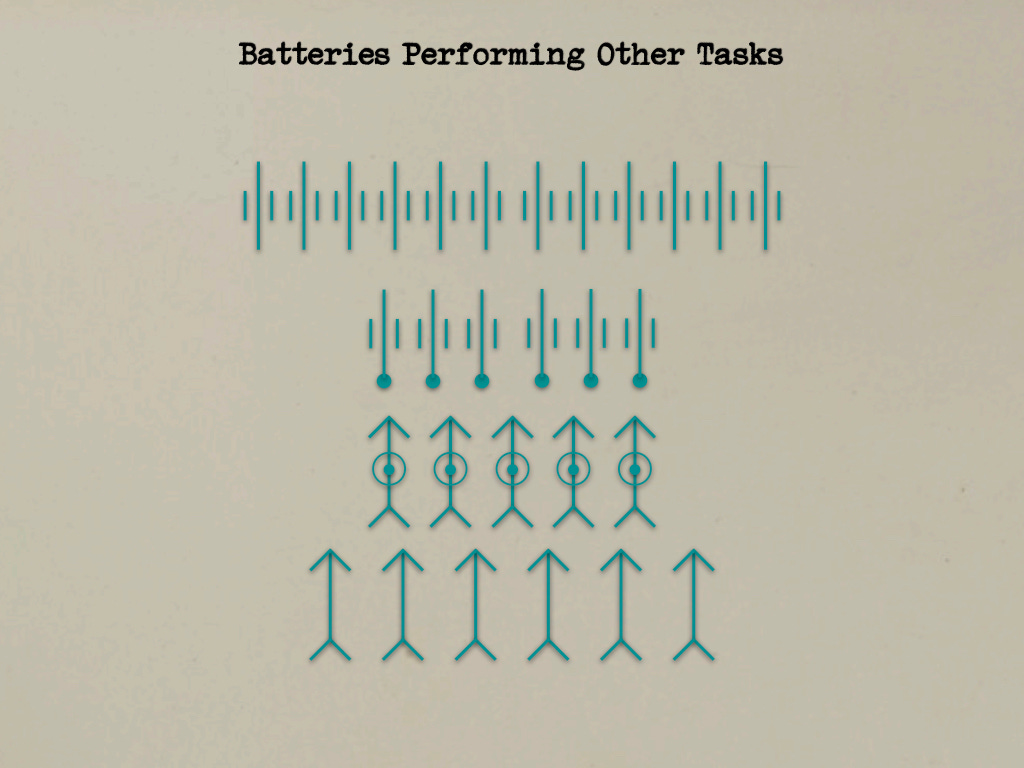

Twenty-eight batteries served purposes other than counter-battery fire or the bombardment of forward trenches. These included light field gun batteries attached directly to infantry regiments and heavy batteries charged with bombarding places likely to harbor counter-attack forces. Most, however, stood ready to fire upon targets identified by German infantry units in the course of their forward movement.

This post concludes a five-part series, the component parts of which can be found at the far end of the following links.

For more about The Tactical Notebook:

In addition to the guns and howitzers of the aforementioned batteries, Balck also provided his ideal division with twelve heavy (25cm) Minenwerfer, twenty medium (17cm) Minenwerfer, and six anti-aircraft guns.

The figures provided by Balck for the last scenario of his article are neither internally consistent nor entirely clear. They do make a little more sense, however, if the phrase “heavy howitzer battalion” is taken to mean a standard divisional heavy artillery battalion of two 15cm heavy field howitzer batteries and one 10cm heavy gun battery.

Fascinating discussion and thanks for sharing it. It is interesting to compare William Balck’s approach to fire support operations in 1918 with those of Georg Bruchmüller (11 December 1863 – 26 January 1948). Bruchmüller typically focused attack operations at the Corps level, not just the division, although the Division Artillery played key roles in comprising and commanding Counterinfantry Groups (IKA), Counterartillery Groups (AKA) and Long Range Artillery Group (FEKA). The percentages were also different in that Bruchmüller weighted the IKA with about 75% of the available batteries and the AKA with about 20% (versus 30%).