William Balck on Field Artillery (IV)

Armies of the First World War

This is the fourth part of a multipart article. For the first three parts, see Balck on Field Artillery (I), Balck on Field Artillery (II), and Balck on Field Artillery (III).

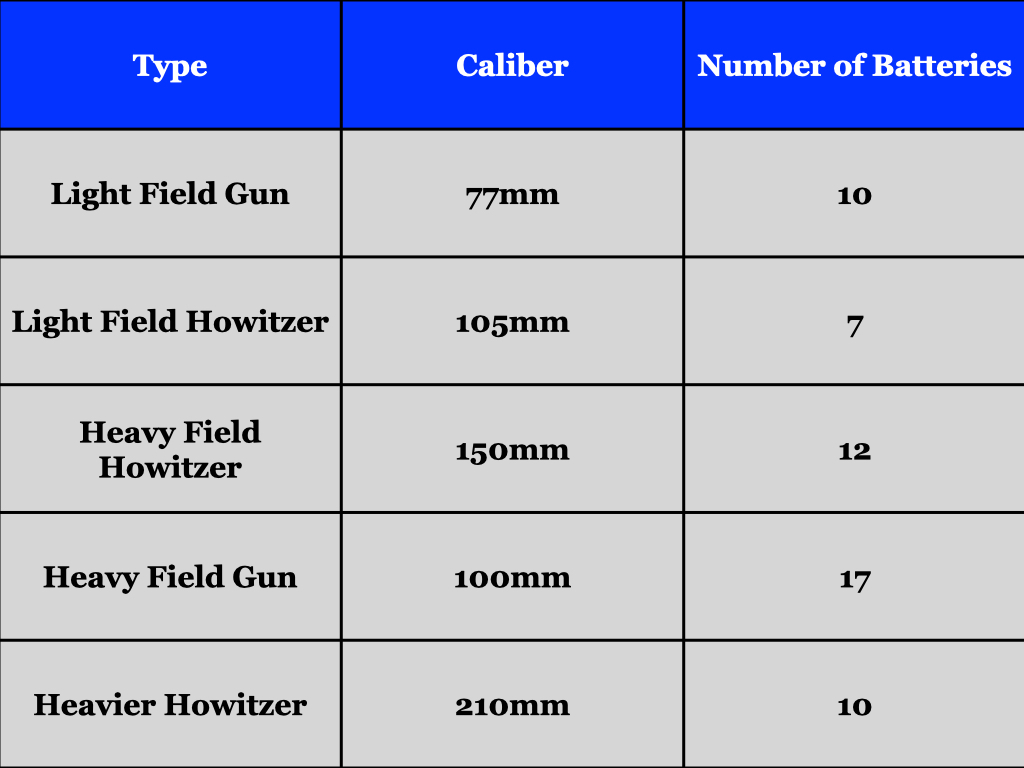

After discussing the limitations of barrage fire, Balck notes that German gunners eventually gave up on the practice in favor of “counter-preparation fire.” The latter technique replaced attempts to cover large areas of open ground with sustained storms of shrapnel bullets with programs aimed at placing concentrations of high-explosive shells upon selected parts of the enemy trench system. (These ranged from shelters and headquarters to observation posts and the junctions of communications trenches.)

Even when provided with high explosive shells, light field guns were poorly suited to tasks of this sort. For one thing, the projectiles that they fired were much smaller than those tossed by howitzers. For another, shells fired by a gun were much less likely to hit a point on the ground than shells fired by howitzers.

To put things another way, the ability of the gunners of an infantry division to conduct effective counter-preparation fire depended upon the possession of large numbers of light (105mm) and heavy (150mm) field howitzers. Thus, it is not surprising that the popularity of counter-preparation coincided with the increase, both absolute and relative, in the number of howitzers serving with infantry divisions.

The light field guns made redundant by the demise of barrage fire found new work in the realm of chemical warfare. The same qualities that had made light field guns the weapon of choice for barrage fire proved valuable when the task at hand was the placement and maintenance of clouds of poison gas over relatively large areas.

This post serves as the fourth installment of a five-part series, the component parts of which can be found at the far end of the following links.

For more about The Tactical Notebook: