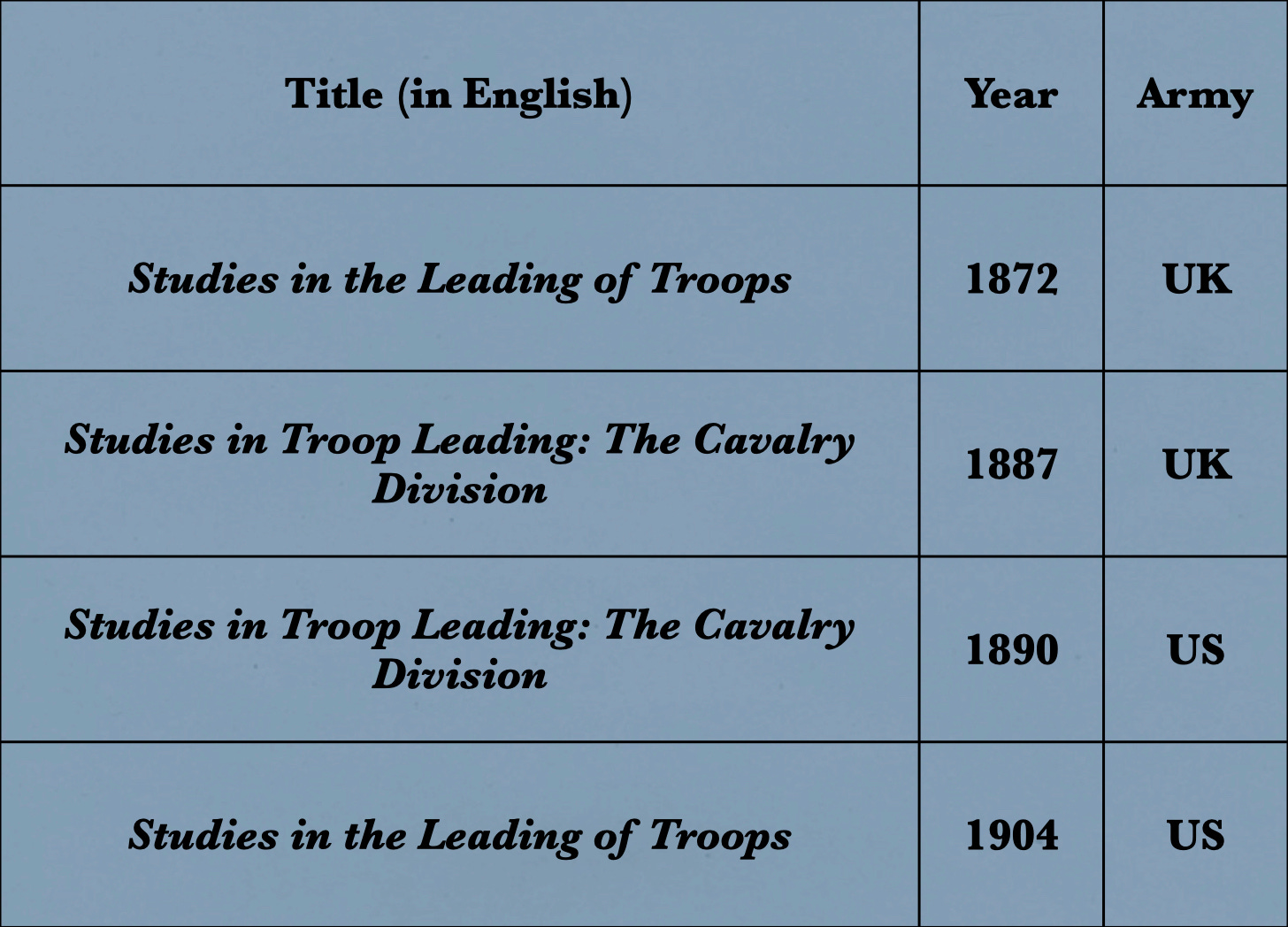

In 1870, a volume of tactical problems rolled off the press of a Prussian publisher.1 Soon thereafter, two British officers made separate translations of this work. The senior of these, Henry Ouvry, rendered the original title of the work, Studien über Truppenführung, as Studies in the Leading of Troops.2 The junior, Henry Hildyard, called his interpretation Studies in Troop Leading.3

For more than a century, people in the English-speaking world followed the example of Colonel Ouvry and Lieutenant Hildyard. Thus, subsequent translators of this book, whether British or American, employed either ‘troop leading’ or ‘the leading of troops’ as the English-language equivalent of Truppenführung.

In the early twentieth century, officers of the US Army built upon this custom by including the term ‘troop leading’ in the names of the collections of tactical problems that they composed. (Like Studien über Truppenführung, these placed students in the role of the general officer commanding a division.)

At first glance, the practice of translating Truppe as ‘troop’ made good sense. Both words, after all, can trace their origin to a common ancestor. Closer inspection, however, uncovers the flaw in this convention: the fact that, in the five centuries since the French expression troupe found new homes in English and German, its descendants have diverged, acquiring new meanings and shedding older ones.

In the age of pike and shot, the words troupe, ‘troop’, and Truppe meant much the same thing. That is, each described a unit of as few as forty, and as many as a hundred, men. In the same era, the plurals of those words - troupes, ‘troops’, and Truppen - could refer to soldiers in general, as in ‘the Parliamentary army fought against the troops of the King’.

Early in the eighteenth century, Francophone folk extended the definition of troupe to encompass formed bodies of any size. Soon thereafter, soldiers in German-speaking lands followed suit, applying Truppe to outfits that were much larger than the Truppen that had been composed of men armed with matchlocks.

As might be expected, the use of a single word to indicate both a handful of men and an organization with several thousand members led to difficulties. French-speaking soldiers solved this problem by reverting to the old practice of reserving troupe for outfits with modest muster rolls. Their German counterparts, however, found a new word to describe small groups of fighting men.

Like Truppe, Trupp descended from troupe. However, while Truppe had traveled directly from France to Germany, Trupp spent a long time in the Netherlands (as troep) before entering the German martial lexicon. In the course of that side journey, moreover, Trupp changed its grammatical gender. (While both die Truppe and la troupe were classed as feminine words, der Trupp belonged to the masculine clan.)

In the nineteenth century, the distinction between Truppe and Trupp made possible the coinage of parallel pairs of compound words. Thus, the Truppenführer, who might command an army corps, division, or combined-arms brigade, practiced the art of Truppenführung. Likewise, the work of the Truppführer, who led a squad, section, or platoon, was sometimes called Truppführung.4

While the two descendants of troupe took root in German, the English language held on to the earlier definition of ‘troop.’ Thus, with the notable exception of the translators of German works with Truppenführung in their titles, twentieth-century Anglophones understood that, while ‘troop’ might describe the equivalent of a platoon or a company, it could not be applied to a battalion or a regiment, let alone a formation commanded by a general officer.

For Further Reading:

To Subscribe, Support, or Share:

Julius Adrian Friedrich Wilhelm von Verdy du Vernois Studien über Truppenführung (Berlin: E.S. Mittler, 1870)

Henry Aimé Ouvry Studies in the Leading of Troops (London: 1872)

Henry John Thoroton Hildyard Studies in Troop Leading (London: H.S. King, 1872)

Where examples of the use of Truppenführung, Truppenführer, and Truppführer abound, I have found but one case of the use of Truppführung.

I have two copies of the Bruce Condell version. 🙂

Lovely!