With this article, the Tactical Notebook continues the serialization of Three Hundred Assaults. Written by Lieutenant Colonel Brendan McBreen, USMC (Retired), Three Hundred Assaults explores the results of an ambitious program of simulations, each of which depicted an assault conducted by a Marine rifle squad. The first five posts in this series can be found by means of the following links.

5. Insights for squad leaders

What can a simulation teach us about the assault that is not already in our manuals? The overarching lesson of this experiment is how lethal the assault can be, even for professionals. Our single, simple tactical problem—assaulting one suppressed and isolated enemy position occupied by only three or four enemy soldiers—was supremely dangerous. Random events and small miscalculations often had deadly results, even for squads doing everything right. When the enemy took evasive action, shifting positions, our squads were shot from a new direction. More enemy, in more interlocking positions, would have been much worse.

a. Find the enemy first. All your tactical decisions are better if you know the enemy’s location. Enemy soldiers with poor camouflage and poor fire discipline are easier to find, but a well-trained enemy can only be found when you see their fire. Inside 50 meters, you have no time to reorient if you assault in the wrong direction and get surprised by close enemy fire.

All Marines need to search for the enemy: “Ten o’clock! Trenchline! One-hundred meters!” Crosstalk between Marines helps situation awareness. Optics help. UAS help.

You then need to tell everyone the enemy’s location to focus the squad’s actions.

If the enemy relocates, you will assault an empty position, and be fired on from a new direction. If a second enemy position opens fire, you will need to change tactics to respond.

b. Shoot first and shoot the most. Overwhelm the enemy with accurate, concentrated, and continuous suppressive fire. Fire superiority keeps their heads down and prevents return fire.

Concentrate fires on one position at a time. Immediately concentrate all fires on any enemy machinegun. Your fire commands prevent dispersed fire.

Concentrate fire teams of suppression. Single weapons are weak and ineffective. Sometimes, even four weapons have gaps in fire, with reloading, stoppages, movement, and casualties.

Concentrate 40mm grenades. The M32 is tremendously valuable against trenches—near misses are still effective. Your squad’s marksmanship insures hits and near misses.

A weak enemy is easier to suppress and takes longer to recover. When effectively suppressed, an enemy with poor leadership or low morale may surrender or panic.

c. Read the dirt. Select routes that protect your Marines. Find terrain with cover—irregular dips and shoulders. Try to see the terrain from the enemy’s point of view. Where is his dead space?

Fifty percent of tactics is dirt. Your techniques are meaningless if you choose poor ground.

Do not get trapped in the open, in the enemy’s beaten zone. Get to dead space quickly.

Terrain, not the individual Marine or his leader, dictates where we can move.

d. Advance using fire and movement. After the SBF stops, you must provide your own suppression while under enemy fire. Fire and movement is not a rote drill, but a tactical evolution with multiple tactical decisions that a leader must direct and control.

Shoot more and move less. Conduct deliberate fire and movement with two fire teams shooting while one fire team moves. Three fire teams provide multiple tactical options.

Each fire team moves to a spot with a good line of sight to fire on the enemy. If not, they move again immediately. They cannot support the squad if they cannot fire. Line of sight is more important than cover.

If your fires become sporadic, stop the squad, reload, and then fire all hands. Regain fire superiority, then continue fire and movement.

Fire and movement is exhausting. Do not race. Do not start until you are fired on. At more than 300 meters, fire and movement is ineffective—you cannot see or shoot the enemy.

e. Other insights from our simulation experiment:

Casualties matter. More than two casualties starts a dangerous downward slide. Your fires slow, enemy fires increase. If you are suppressed, you cannot move to cover. Any treatment of your own casualties further reduces your firepower. You must regain fire superiority—everyone must fire—or you’ll be pinned in the open and more casualties will occur.

Enemy skills matter. Your decisions and tactics are different for strong versus weak enemies. Even one or two well-trained enemy soldiers can decimate your squad. The weaker the enemy, the more successful the assault. Enemies with low alert levels, poor battlefield awareness, unsure leadership, and bad morale are surprised and unnerved by your assault.

Enemy size matters. The enemy on the objective should be as small and as weak as possible. Ideally, his condition should be wounded, wet, suppressed, cold, and exhausted. Avoid assaulting a large number of well-trained, vigorous enemy soldiers defending multiple, well-prepared, and mutually supporting positions.

Marksmanship matters. Effective suppression is hits and near misses. Well-aimed fire is especially important against enemy trenches, fighting holes, and buildings. Marines can close on a hardened position only when it is effectively suppressed and the enemy is cowering. Distance benefits the better marksmen.

Fighting holes matter. Trenches, fighting holes, and buildings protect the enemy. Your fires cannot kill an enemy ducked inside a hardened position. When your suppression stops, the enemy recovers and fires back. A single remaining soldier, if well-protected, can shoot your entire assault element. But visible fighting holes do help your squad locate the enemy.

Suppression is temporary. Suppressive fire, both indirect and direct, has no long-term effect. The enemy is not stunned for twenty minutes. When your suppression slows to intermittent fire, the enemy recovers and fires back. Well-trained and well-led enemies recover faster than weak enemies. Your suppression should be nearly continuous.

Speed matters. Move fast when the enemy is suppressed so that he does not have time to respond or reposition. Alternate bursts of speed with slower deliberate actions during fire and movement. Avoid making hasty decisions and avoid rushing into open terrain.

Exhaustion matters. A long slow approach is deadly—Marines cannot crawl 100 meters. A long, rapid approach is also deadly—Marines cannot run 400 meters or hit the deck thirty times. Exhausted Marines shoot poorly, move slower, and make bad tactical decisions.

Distance matters. Assault from as close as possible, but only if you know the exact location of the enemy. A close assault surprises and overwhelms the enemy and exposes your squad for a shorter amount of time. Fire and movement should be as short a distance as possible.

Smoke is unreliable and unpredictable in the wind. Shoot 40mm smoke at the enemy to blind. Do not throw hand smoke in front of your own position, except as a feint. It identifies your position, blocks you vision, and causes your unit to bunch up and lose direction.

Avoid enemy machineguns. Do not assault a well-sited and dug-in machinegun from beyond 100 meters when it is facing you. Assault a machinegun from the flank, close and fast. An enemy machinegun caught in the flank cannot be repositioned quickly.

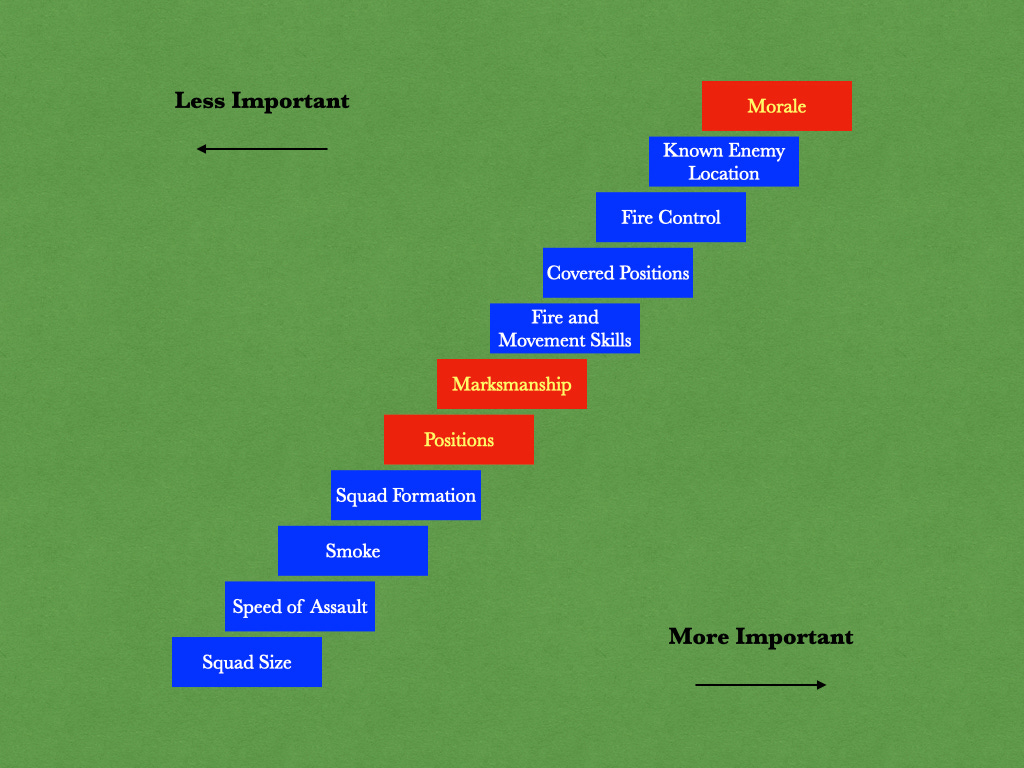

f. Features of a successful assault. What actions, attributes, or features are most important to a successful assault? Based on our experiment, we prioritized the varying attributes of any assault.

Enemy weaknesses. The listed enemy weaknesses (depicted in red on the diagram) may or may not exist, but before an assault starts, fire from the support element might destroy a weak enemy’s will to fight. An aggressive assault may cause a poorly-led enemy to panic and run. During the assault, the enemy’s poor marksmanship, fire discipline, badly-sited positions, and insufficient camouflage all increase the odds that the assault will be successful.

Friendly strengths. Unlike enemy weaknesses, friendly strengths (depicted in blue) can be learned and trained. In the friendly feature list on the left side of the table, a known enemy location was determined to be the first priority. Every decision that a leader makes is better if the enemy’s location, size, orientation, and type of defensive position is known. UAS would help. The ability of a squad leader to concentrate overwhelming fire on a specific enemy position was the second most important feature of a successful assault. All Marines need a position with a good line of sight to fire on the enemy. This is more important than cover.

Terrain was next. To close on the enemy, Marines need cover. Leaders select terrain that protects Marines and masks them from enemy fires. This was followed by fire and movement skills—the practiced teamwork and assault SOPs that enable the squad to advance under the protection of their own suppressive fires. Fire and movement requires training and practice.

The ability to smoke the enemy was the next key feature, lower on the list. A fast assault was good, but not required. Sometimes deliberate actions and tactical patience were better, to avoid making hasty mistakes. After speed, the least important features of a successful assault were squad formations and squad size.