Three Hundred Assaults (IV)

The Rifle Squad as Part of the Platoon Attack

With this article, the Tactical Notebook continues the serialization of Three Hundred Assaults. Written by Lieutenant Colonel Brendan McBreen, USMC (Retired), Three Hundred Assaults explores the results of an ambitious program of simulations, each of which depicted an assault conducted by a Marine rifle squad. If you haven’t done so already, you will want to begin with the introduction to the article, which can be found below.

4. 300 Results

The results from all six scenarios, 300 assaults, are plotted on the six charts below, each assault at a distance of 400, 200, 100, or 50 meters. The success of the assault was defined as the remaining combat power of the squad—a function of casualties—plotted on the vertical axis. Each casualty increasingly reduced the combat power of the squad.

The top half of the chart is mission success—the enemy was destroyed, captured, or ran away. The bottom half of the chart, shaded gray, is mission failure—the enemy remained in position.

A successful assault that suffered zero casualties was plotted at 100 percent combat power, the top line of the chart. A successful assault with four casualties was plotted at 70 percent. An unsuccessful assault that incurred two casualties was plotted in the gray bottom half of the table at 88 percent. The squad is still capable, but they did NOT destroy the enemy. An unsuccessful assault that was pinned down and destroyed with nine or more casualties was plotted in the gray bottom half at 0 percent combat power. The squad failed its mission and was combat ineffective. See Appendix B for the relationship between casualties and combat power. See Appendix C for an example data sheet.

a. Scenario A. Assaults against three enemy conscripts with automatic rifles lying in the open grass and facing the assault element. A conscript enemy with bad marksmanship, located and exposed in the open, was quickly overwhelmed by a heavy volume of accurate suppressive fire.

Scenario A. Assaults against three enemy conscripts with automatic rifles lying in the open grass and facing the assault element (n = 50).

(1) At 400 meters, all twenty assaults succeeded. Four assaults incurred one casualty each. The conscript enemy usually fired early, and poorly, giving away his position. Assaulting squads used fire and movement to advance. Well-aimed fire from behind cover suppressed the enemy. Conscript enemy soldiers with low morale often surrendered or ran away in panic.

(2) At 200 meters, all ten assaults succeeded without any casualties. Enemy positions on the crest were silhouetted, found immediately, and overwhelmed with fire. Enemy positions back from the crest without visibility suffered a lack of battlefield awareness. Assaulting squads advanced by fire and movement, found covered ground, and used 40mm grenades on the enemy in the open to increase effective suppression.

(3) At 100 meters, all ten assaults succeeded. Squads crested the last rise online using assault fire behind smoke. Enemy positions in the open were easy to find and overwhelm with fire. One squad suffered two casualties when an unseen enemy shot first into the smoke.

(4) At 50 meters, most assaults quickly destroyed the enemy. But three times, when the enemy stayed hidden and held their fire, the assaulting squad was surprised by fire. One assault ended in disaster when a hasty, bunched up squad, rushing in front of a hidden enemy, was caught in the open.

b. Scenario B. Assaults against three enemy conscripts with automatic rifles manning a fighting hole and facing the assault element. An ill-trained enemy, even in fighting holes, was overwhelmed by effective suppression. Visible fighting holes delayed the destruction of the enemy, but enabled the squad to locate his exact position and shoot first—important to avoid surprises and suppress any return fire from the enemy.

Scenario B. Assaults against three enemy conscripts with automatic rifles manning a fighting hole and facing the assault element (n = 40).

(1) At 400 meters, all ten assaults succeeded. Three assaults suffered casualties. The enemy’s poor marksmanship gave away his position. Aggressive fire and movement panicked the enemy, and his low morale drove him to surrender or run more than half the time.

(2) At 200 meters, all ten assaults succeeded. Most assaults executed deliberate fire and movement with three fire teams, enabling the squad to locate and then mass fires on the enemy. Two cases suffered casualties when hasty movement pushed one fire team over the crest without the mutual support of the other two teams. In one unfortunate case, the entire squad rushed past a hidden enemy position and surprise fire wounded six. Fighting holes protected the enemy when suppressed, but only delayed his eventual destruction.

(3) At 100 meters, all ten assaults succeeded. Friendly casualties were all caused by short-range surprise fire from hidden enemy positions. Shooting first is important to the enemy, especially with poor marksmanship, but immediate friendly return fire overwhelmed the enemy every time, even in their fighting holes.

(4) At 50 meters, all ten assaults succeeded. Two hasty assaults, bunched up in the open, were surprised by enemy fire and suffered four and seven casualties. These casualties reduced the squad’s ability to return fire, find cover, or move, which would have been disastrous against a determined enemy with better marksmanship. At close range, finding the enemy and shooting first is more important than at farther ranges.

c. Scenario C. Assaults against three enemy conscripts manning a machinegun in a fighting hole and facing the assault element. A machinegun manned by conscripts was still deadly, but it was successfully defeated by deliberate fire and movement—two teams fired continuously to maintain suppression, while one team moved to the next covered firing position. Marines caught in the open were often casualties.

Scenario C. Assaults against three enemy conscripts manning a machinegun in a fighting hole and facing the assault element (n = 40).

(1) At 400 meters, nine of ten assaults succeeded, but averaged over three casualties per assault. Long assaults increased exposure to machinegun fire. Cover was not always available. When the assaulting squad was engaged at 400 meters, they could not return fire to suppress. One disastrous assault was pinned in the open for six minutes, lost all ability to return fire, and then crawled back out of the beaten zone behind smoke.

(2) At 200 meters, all ten assaults succeeded, but averaged almost two casualties per assault. Fire and movement was executed slowly and deliberately, with two teams firing to ensure continuous suppression of the machinegun and one team moving to cover. Two assaults suppressed the wrong position, but were able to change targets before the final assault.

(3) At 100 meters, all ten assaults succeeded, but the enemy machinegun caused casualties seven out of ten times. When the enemy relocated to an alternate position—five times—the assaulting squad had to change direction and tactics while under fire. One assault used smoke on one flank to misdirect the enemy’s fire.

(4) At 50 meters, five close assaults quickly overwhelmed the enemy with no casualties, crawling forward, firing first, and suppressing the panicked machinegun team. Two assaults were disasters. One was pinned in the open while assaulting the wrong position, and one was shot up while trying to assault behind smoke.

d. Scenario D. Assaults against three well-trained enemy soldiers with automatic rifles lying in the open grass and facing the assault element. Three well-trained enemy soldiers, even without cover, were deadly when they remained hidden. Unlike conscripts, this enemy recovered faster from suppressive fire and reoriented quickly when surprised. Assaulting squads were successful when they concentrated overwhelming and accurate suppressive fire on the enemy.

Scenario D. Assaults against three well-trained enemy soldiers with automatic rifles lying in the open grass and facing the assault element (n = 50).

(1) At 400 meters, all ten assaults succeeded—six with casualties. Against an enemy silhouetted on the crest of the hill, concentrated fires led to success. When the enemy was positioned back from the crest, without visibility, the assaulting squad advanced behind covered ground. The final assaults surprised the enemy and were effective at close range. One near-failed assault suffered multiple casualties when the assaulting squad was pinned without cover at 200 meters in open ground.

(2) At 200 meters, all ten assaults succeeded—but six assaults suffered four or more casualties. Fire and movement, using 40mm grenades to increase suppression, enabled squads to close on the objective. Squads used covered ground and made multiple successful assaults over the crest, on-line, with smoke. The less-successful attacks suffered when the enemy stayed hidden and opened fire late, one time wounding six Marines by shooting into the smoke.

(3) At 100 meters, all ten assaults succeeded—five without casualties. Rapid fire and movement using covered ground, followed by dispersed, on line assault fire behind smoke, worked well multiple times. One near-failed assault was almost destroyed by a single stubborn, well-trained and accurate enemy soldier, unseen in the tall grass.

(4) At 50 meters, most assaults quickly overwhelmed the enemy. But 20 percent of the assaults (4 of 20) ended in disaster when squad leaders had difficulty locating the enemy. The orientation of the enemy did not matter—enemy infantry that was not facing the expected assault repositioned quickly and opened fire in less than one minute. The location of the enemy, hidden in vegetation or tall grass, mattered more than orientation.

(5) Note. The outliers—the circled assaults—cannot be discounted. At every distance, one or two assaults (10 or 20 percent), were pinned down by the enemy and nearly destroyed—usually because the squad could not locate the enemy. Even in open terrain, three well-trained soldiers who can stay hidden can destroy a friendly squad.

e. Scenario E. Assaults against four well-trained enemy soldiers with automatic rifles manning a fighting hole and facing the assault element. A well-trained enemy is dangerous at all ranges, but when his fighting position is visible, it can be continually suppressed by well-coordinated fire and movement—two fire teams shooting while one moves. The priorities are (1) find the enemy, (2) smother with suppressive fire, and then (3) move forward using covered terrain.

Scenario E. Assaults against four well-trained enemy soldiers with automatic rifles manning a fighting hole and facing the assault element. A rapid assault against enemy in the open overwhelms the position (n = 40).

(1) At 400 meters, all ten assaults succeeded with varying levels of casualties. The key actions for the best assaults included pinpointing a visible enemy position early and suppressing it with fire. No smoke was used. The worst assaults, with four or more casualties, had fire teams pinned in the open before the squad gained fire superiority.

(2) At 200 meters, nine of ten assaults succeeded. Two assaults initially suppressed the wrong enemy position, but then stopped, gained fire superiority, and moved on. The slowest assault ran low on ammunition and the enemy was able to recover from being suppressed. One disastrous failure resulted from a hasty squad rush to a distant position. The enemy caught them in the open, the squad never gained fire superiority, and casualties mounted.

(3) At 100 meters, eight of ten assaults succeeded, most with four or fewer casualties. These assaults maintained almost 100% suppression, 100% of the time, allowing fire teams to close to within grenade range. Casualties usually occurred before suppression started when the enemy shot first. The two failed assaults moved against the wrong position and were pinned in the open, one on the far side of a crest with no mutual support.

(4) At 50 meters, six assaults had two or fewer casualties. Most of these assaults crawled forward under the enemy position in the dead space beneath the crest and used assault fire to mass weapons on the enemy from close range. No smoke was used. The four assaults with six or more casualties were impatient, rushing to poor positions without suppression.

(5) Note. During two assaults, one at 400 meters and one at 100 meters, the fire and movement technique evolved into an actual squad flank attack. Two fire teams maintained their initial positions, not moving, and essentially became a stationary SBF with excellent line of sight and suppressive effects on the enemy. The third fire team was able to bound multiple times in a row, flanking and then destroying the enemy position.

f. Scenario F. Assaults against three well-trained enemy soldiers manning a machine gun in a fighting hole and facing the assault element. Squads that assaulted a well-trained machinegun team from beyond 100 meters were all destroyed. Assaulting squads inside 100 meters were successful only half the time, but with significant casualties. A rapid assault, across a short distance, against a known enemy location, surprising the machinegun that was not facing the assault, overwhelmed the enemy 80 percent of the time.

Scenario F. Assaults against three well-trained enemy soldiers manning a machinegun in a fighting hole and facing the assault element (n = 80).

(1) At 400 meters, all ten assaults failed. Long-range machinegun fire caused casualties before the squad could even see or range the enemy. A long, slow approach increased the amount of time the squad lacked cover, and increased the time the machinegun could track targets. Some assaults raced to the dead space at the base of the hill and then attempted a 50 meter assault. Long assaults were exhausting and difficult to control.

(2) At 200 meters, all ten assaults failed. Two raced to defilade at the base of the hill with enough combat power to conduct a 50 meter assault. Fire and movement could not suppress the distant, dug-in machinegun. Squads had difficulty finding multiple covered positions across a long distance inside the machinegun beaten zone. Three assaults, after suffering casualties, used smoke to conceal their movement, and then outran the smoke.

(3) At 100 meters, against an alert machinegun facing the assault, half of ten assaults failed completely. Squads were pinned in the open, unable to move. One squad had eight Marines shot in the first 40 seconds. The five successful assaults all used smoke. But smoke was unreliable. One assault, where the smoke drifted onto the enemy, suffered only one casualty. But the other four assaults behind smoke suffered increased casualties.

When the machinegun was surprised at 100 meters, most squads were successful. The open boxes—representing a machinegun NOT facing the assault—show 19 of 20 successful assaults, most with zero casualties. Rapid assaults across 100 meters destroyed the enemy before he could reposition his machinegun. Five of 20 assaults, where the enemy turned his weapon quickly, did suffer casualties. One slow assault was a disaster.

(4) At 50 meters, against an alert machinegun facing the assault, every one of 20 squads, 100 percent, incurred casualties. Half of the squads destroyed the enemy, but suffered significant losses, and five squads were destroyed completely. When the enemy shot first inside 50 meters, the results were disastrous.

When the machinegun was surprised, facing the wrong direction, the enemy had no time to respond. At 50 meters, every one of ten squads, 100 percent, quickly overran the enemy with assault fire in less than a minute without casualties.

(5) Note. An enemy machinegun, firing at you, is a known position. This simplifies the squad leader’s job. None of the 80 assault squads in this scenario—half of whom failed utterly—were confused by unknown or hidden enemy positions.

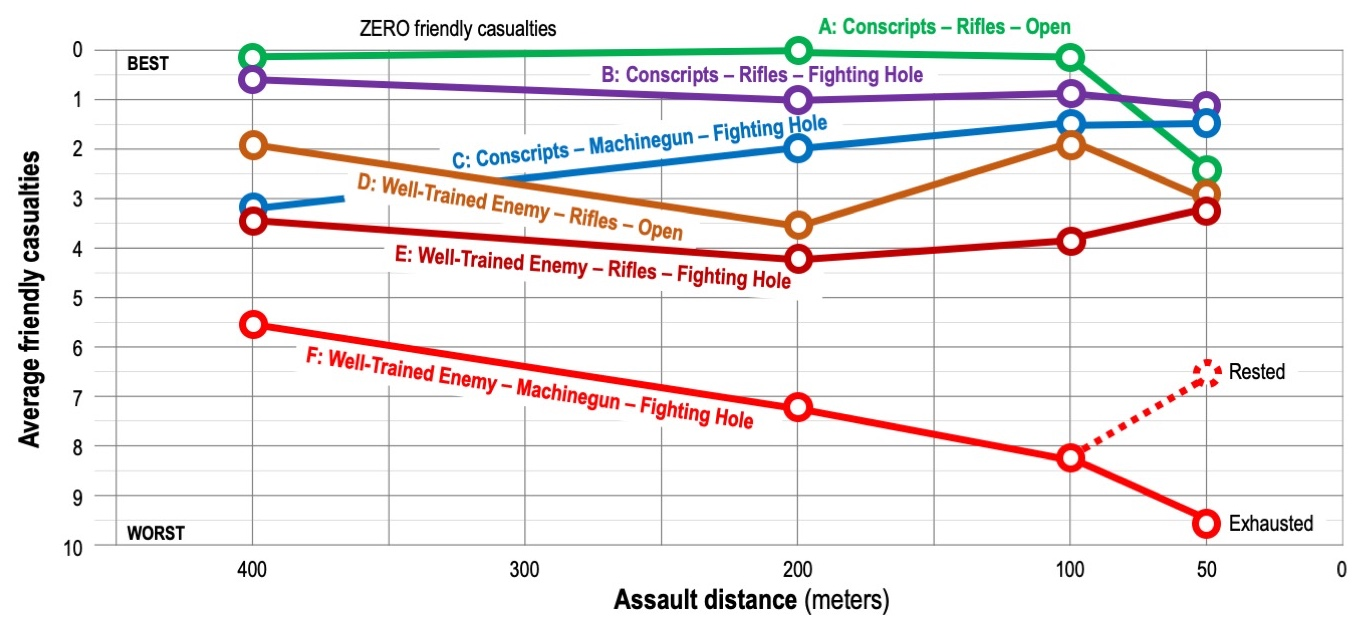

g. Scenario trends. As the skill, protection, and weaponry of the enemy increased with each scenario, the average number of friendly casualties increased. Long-distance assaults did not always incur more casualties than shorter assaults. Although shorter distances were not as exhausting and did not expose the assault element to as much fire, any mistake made by the squad during a short assault—an incorrect enemy location, a bad direction, or a hasty rush to an exposed position—could not quickly be corrected and often resulted in exposure to enemy fire.

Scenario Summary. Average friendly casualties when assaulting against increasingly difficult enemies: Scenarios A through F (n = 300 assaults and over 700 casualties). Note: In the Scenario F data, “Exhausted” squads suffered an average of 9.6 casualties after having already moved 400 meters under fire. “Rested” squads assaulted only 50 meters.

The biggest advantage of a long assault was that the enemy usually fired early and confirmed their position, weapons, and numbers to the assaulting squad. Most casualties inside 50 meters occurred when the enemy position was not known—or had moved—and the assaulting squad was surprised. Fighting holes protected the enemy but they also clearly located their position and helped focus the fires of the assaulting squad.

For most of the 300 assaults, the enemy was facing the assault element—the worst case. When the enemy was surprised, not facing a near assault, friendly casualties were often zero. But the assault element could not know the enemy orientation before starting the assault.