Three Hundred Assaults (I)

The Rifle Squad as Part of the Platoon Attack

With this article, the Tactical Notebook continues the serialization of Three Hundred Assaults. Written by Lieutenant Colonel Brendan McBreen, USMC (Retired), the series explores the results of an ambitious program of simulations, each of which depicted an assault conducted by a Marine rifle squad. The first post in this series, Three Hundred Assaults (Abstract) can be found at the other end of the following link.

300 Assaults: The Rifle Squad Assault as Part of the Platoon Attack

What can a simulation teach us about the assault that is not already in our manuals?

1. What are the questions?

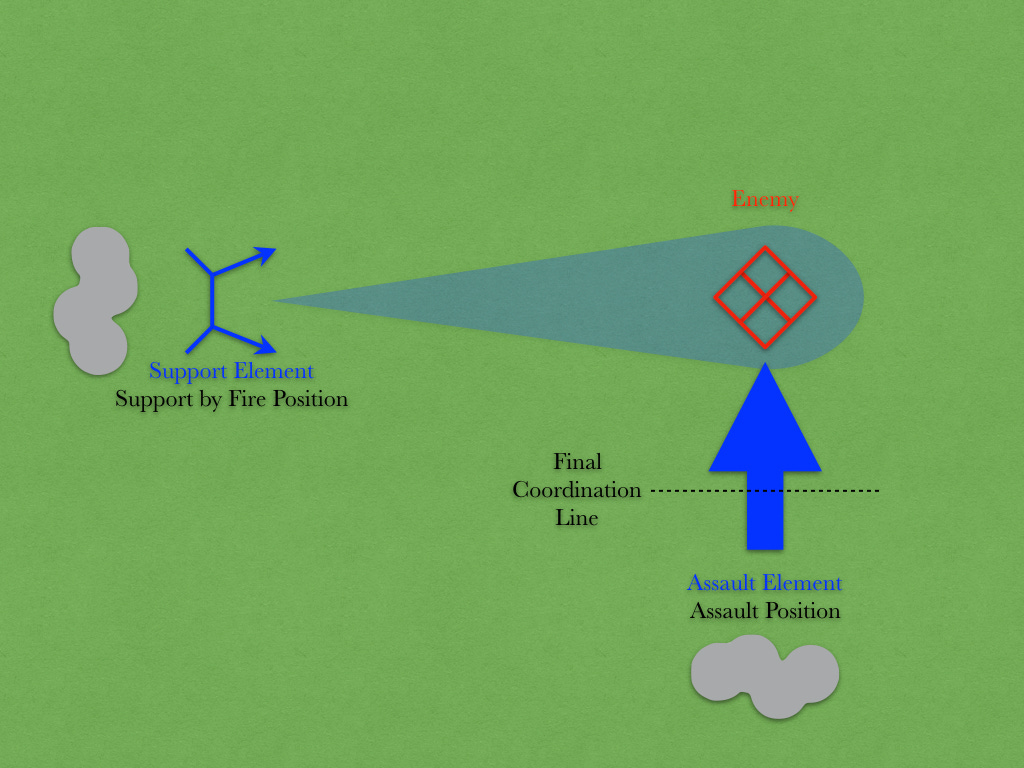

I teach lieutenants. Recently, I talked to two young officers, both graduates of The Basic School (TBS) and the Infantry Officer Course (IOC), who were keenly interested in tactics. We talked about the platoon attack, an operation that I have executed, trained, studied, and taught as a Marine infantry officer for twenty-five years. I wanted to impress upon them how complex even a simple evolution could be. On a white board, I drew a diagram and quizzed them on what they had learned:

Q: “Lieutenants. During the attack, when do you stop your support by fire (SBF) machineguns?”

A: “Sir. Right before they shoot the assault element. At the final coordination line (FCL).”

Q: “Is that the same as your assault position?”

A: “No. We start the assault at the assault position, which should be very close to the FCL.”

Q: “And that’s where you do fire and movement?”

A: “No. We start fire and movement only when we’re fired on. That’s just one part of the assault.”

Q: “So if the enemy is completely suppressed, the assault element doesn’t do fire and movement?”

A: “Correct. We want to move as close to the enemy as possible, as fast as possible.”

My next questions were a bit more challenging:

Q: “If fire and movement is just one assault technique, what are the others?”

A: “Running. Movement to the objective. Then fire and movement. Are there others?”

Q: “Does fire and movement before the FCL mean that the support-by-fire (SBF) has failed to suppress the enemy?”

A: “Not necessarily. But assault techniques during the SBF should be different than they would be after the SBF.”

Q: “During fire and movement, do you move by fire teams or buddy teams? Or individuals?”

A: “Buddy teams. But fire teams are better at massed suppression. What does the manual say?”

Q: “If you deploy online at the assault position, what is the the probable line of deployment (PLD)?”

A: “Isn’t the PLD only used for a night attack? Is it located before or after the assault position?”

My third set of questions was even more detailed. I wanted the lieutenants to think about specific tactical decisions and how they might develop their own judgement, expertise, and observation skills.

Q: “How do you know when the enemy is suppressed? What clues do you look for?”

Q: “Which assault technique is best in which situation? Against what types of enemy positions?”

Q: “How does a squad leader direct fire and movement when no one can hear him?”

Q: “What is more important—deliberate movement to find cover or speed of the assault?”

Q: “What if the enemy is not firing at you and you don’t know his location?”

Q: “Which enemy weakness is better for us—poor marksmanship or poor morale?”

Q: “How do you assault an enemy machinegun? Are there types of positions that we should avoid?”

Q: “When do you use smoke? On them or on us?”

None of these questions had easy answers, but the professional discussion was rewarding. Instructors like me often tell lieutenants, “It depends on the situation,” but that’s exactly what we were asking: “What specific situations require what decisions by what leaders?”

Q: “So after the suppression stops, your assault element is left all alone advancing on the enemy?”

A: “Yes?”

They had never thought about that. During an attack, supporting units can bring tremendous fires down onto the enemy. Fixed-wing and rotary-wing close air support, artillery, rockets, and missiles destroy enemy fortifications, buildings, equipment, and trucks. Armored vehicles fire heavy machineguns, and mortars tear into enemy positions. The enemy is shocked by our firepower. Eventually, however, all indirect fires stop. Our machineguns and other company-level weapons continue to suppress the adversary as our assault element moves up towards the enemy position. Then, when the risk of friendly fire is too great, even our stationary suppressive fires stop. The contributions of every supporting unit go to zero. All fires cease. The battlefield shrinks to a single 100-meter square. And the squad assaults alone.

How? How do they fight? What do those ten or twelve Marines actually do? What do we teach? What decisions do they make? What exactly do we mean when we say, ‘they assaulted the objective’?

For Further Reading: