Three General Staffs

Armies of the German Empire

On the eve of the First World War, the organization often called ‘the German General Staff’ was, strictly speaking, neither German, nor general, nor a staff.1 Rather, it was a lopsided troika composed of three distinct corps, each of which belonged to the military establishment of one of the three largest states of the German Empire.

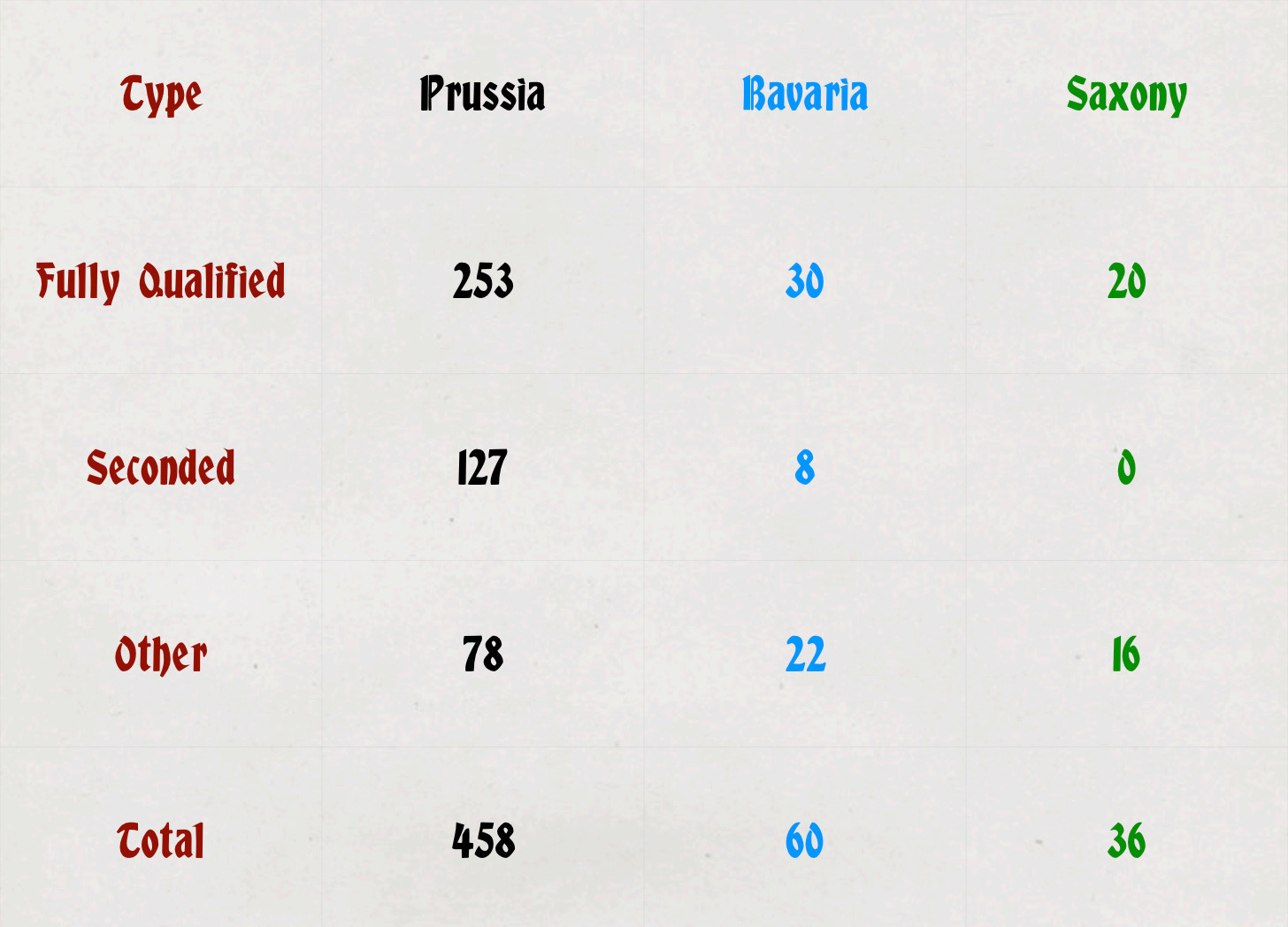

The most populous of these three ‘general staffs’ belonged to the largest (by far) of the building blocks of the German Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia. In time of peace, it planned operations, and conducted grand maneuvers, for both the largest kingdom of the Reich (Prussia) and the smallest (Württemberg). It also provided similar services for the Empire as a whole.

In 1910, 458 officers served on the Prussian General Staff. Of these, 253 were fully qualified members of that corps. That is, having graduated from the Kriegsakademie and served demanding periods of probation (of one, two, or three years), they had earned a permanent transfer from their regiments of origin to the General Staff. (The most obvious indication of this was the wearing of the distinctive uniform of the General Staff Corps.)

The other officers serving with the Prussian General Staff retained their memberships in their old regiments. Of these, most were recent graduates of the Kriegsakademie who had been ‘seconded’ (kommandiert) to the General Staff in order to serve the aforementioned periods of probation. (A small number of specialists in siege warfare, whether engineers or gunners, also belonged to the category of ‘seconded’ officers.) The rest wrote military history, made military maps, or did work related to the mobilization of the German railroad network.

The general staffs of the kingdoms of Bavaria and Saxony paled in comparison their Prussian counterparts. This difference owed much to the relative sizes of the contingents supplied by those kingdoms. It also resulted from the absence of program for probationary service in the Saxon general staff.

Sources:

Anonymous ‘La Carrière de l’Officer d’État-Major Allemand’ [‘The Career of an Officer of the German General Staff’] Revue Militaire des Armées Étrangères [Military Review of Foreign Armies] (October 1910) page 328-355.

Prussia, Geheime Kriegs-Kanzlei [Privy War Chancellery] Rangliste der Königlich Preussischen Armee und des XIII. (Königlich Württembergischen) Armeekorps [List of Officers of the Royal Prussian Army and the XIII. (Royal Württemberg) Army Corps] (Berlin: E.S. Mittler, 1910) pages 15-29

Saxony, Kriegsministerium [War Ministry] Rangliste der Königlich Sächsischen Armee für das Jahr 1910 [List of Officers of the Royal Saxon Army for 1910] (Dresden: C. Heinrich, 1910) pages 6 and 7

Bavaria, Kriegsministerium [War Ministry] Militär-Handbuch des Königreichs Bayern [Military Handbook for the Kingdom of Bavaria] (Munich: Kriegsministerium, 1907) pages 10-11 and 179

Credits for Illustrations:

Coats of Arms: David Liuzzo (Prussia), Grandiose (Bavaria), Saxony and Württemberg (Glasshouse)

Base Map: Milenioscuro

For Further Reading:

This turn-of-phrase echos the often-quoted words of Voltaire ‘This body that called itself, and is still called, the Holy Roman Empire was in no way either holy, or Roman, or an empire.’ [Ce corps qui s’appelait, et s’appelle encore, le saint empire romain n’était en aucune manière ni saint, ni romain, et ni empire.] Oeuvres de Voltaire: Essai sur les moeurs (Tome 16) (Paris: Lefèvre, 1829) page 316

“The rest wrote military history, made military maps, or did work related to … mobilization “

Add working in industries related to the military and I think this the best staff preparation.

As opposed to our endless bureaucratic buffooneries.