Early in 1942, Franklin Delano Roosevelt faced a dilemma. For a variety of reasons, both strategic and sentimental, he wished to devote the lion’s share of America’s military, industrial, and financial might to the war in Europe. His allies in the Pacific, however, believed that the United States should focus its efforts against Japan. Closer to home, polls suggested that, thanks to recent memories of the attack on Pearl Harbor, far more Americans also preferred a policy of ‘Asia first’.

President Roosevelt addressed this problem with a long-range strike. On 18 April 1942, sixteen American bombers, launched from the deck of an aircraft carrier, dropped bombs aimed at military and industrial facilities in four Japanese cities.

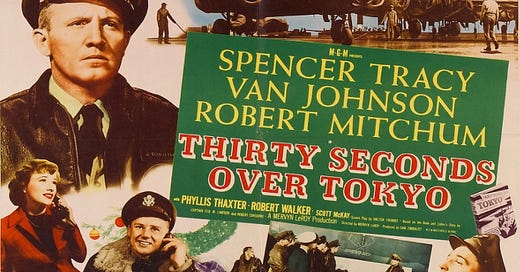

Known to history as the ‘Doolittle Raid’, this attack did little in the way of physical damage, and nothing to hinder the many successful offensives that Japanese forces were conducting at the time. What the distant delivery of bombs did do, however, was remind Australians, Chinese, and New Zealanders, as well as westward-looking Americans, that the government of the United States had not forgotten about its war against Japan. (The Doolittle Raid also worked much mischief upon the minds of Japanese decision makers. The story of those effects, however, is a tale for another day.)

On 28 April 1942, in the first ‘fireside chat’ after the Doolittle Raid, Roosevelt made a brief, almost off-hand, mention of the strike. ‘It is even reported from Japan’, he said, ‘that somebody has dropped bombs on Tokyo, and on other principal centers of Japanese war industries. If this be true, it is the first time in history that Japan has suffered such indignities.’ This 39-word announcement, however, paled in comparison to the 336 words Roosevelt devoted to matters related to France and its colonies, let alone the 1,008 words he employed to describe the many limits he intended to impose upon the pedestrian freedoms enjoyed by ordinary Americans.

Roosevelt may well have engaged in this little exercise in humble-bragging in order to draw the attention of his audience in the direction of the Doolittle Raid. (‘What, this old dress? I only wear it when I don’t care how I look.’) It is also quite possible that the under-statement served to buttress one of the central messages put out by pro-war propagandists in the United States: the notion that Germany, Italy, and Japan were but local avatars of an indivisible enemy.

The replacement of piloted bombers by guided missiles and high-endurance drones has deprived long-range strikes of some of their ability to signal commitment. That is, rather than being the work of some of the most celebrated warriors of a given state, who risk life, limb, and liberty to count coup upon the enemy heartland, the present-day analogs have, to a large extent, become the work of robots, which, being machines, can be sent into harm’s way more easily than human beings.

Nonetheless, in situations where geography permits, long-range strikes can replicate the role that the Doolittle Raid played in the great clash of coalitions of that we call the Second World War. That is, they allow a state to single out one of its antagonists for special treatment, thereby exploiting the inclination of people, both foreign and domestic, to play favorites among their enemies.

Sources:

Books and articles about the Doolittle Raid are like unto the cats of Istanbul. Of these many works, I made greatest use of James M. Scott Target Tokyo: Jimmy Doolittle and the Raid That Avenged Pearl Harbor (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016).

The transcript of the ‘fireside chat’ of 28 April 1942, On Sacrifice can be found on the website of the Miller Center for Public Affairs, University of Virginia.

My characterization of the public information problem borrows much from the third chapter of Steven Casey Cautious Crusader: Franklin D. Roosevelt, American Public Opinion, and the War Against Nazi Germany (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001).

For Further Reading:

To Subscribe, Support, or Share:

The difference also might that long range precision weapons are for lack of a better word “antiseptic” from the comfort of the high backed leather chairs in the situation room at the White House the decision to launch a cruise missile verses say SEAL Team Six to kill Bin Laden provides comparison and contrast to go or no go. No president these days wants to head out to Dover AFB to receive the flag draped coffins of our dead military men and women. A cruise missile on a virtual suicide mission? Pretty easy choice. One that maybe ought not be so easy…

Or 30 seconds over Kharg Island?