The Incursion West of Kursk

The Russo-Ukrainian War (2024)

Quiet fronts have formed in many wars. Indeed, until the great explosion in the size of armies of the late eighteenth century, the concentration of forces into a small fraction of the space available to them often resulted in situations in which substantial bits of real estate were guarded by little more than a handful of gendarmes and the occasional fortress.

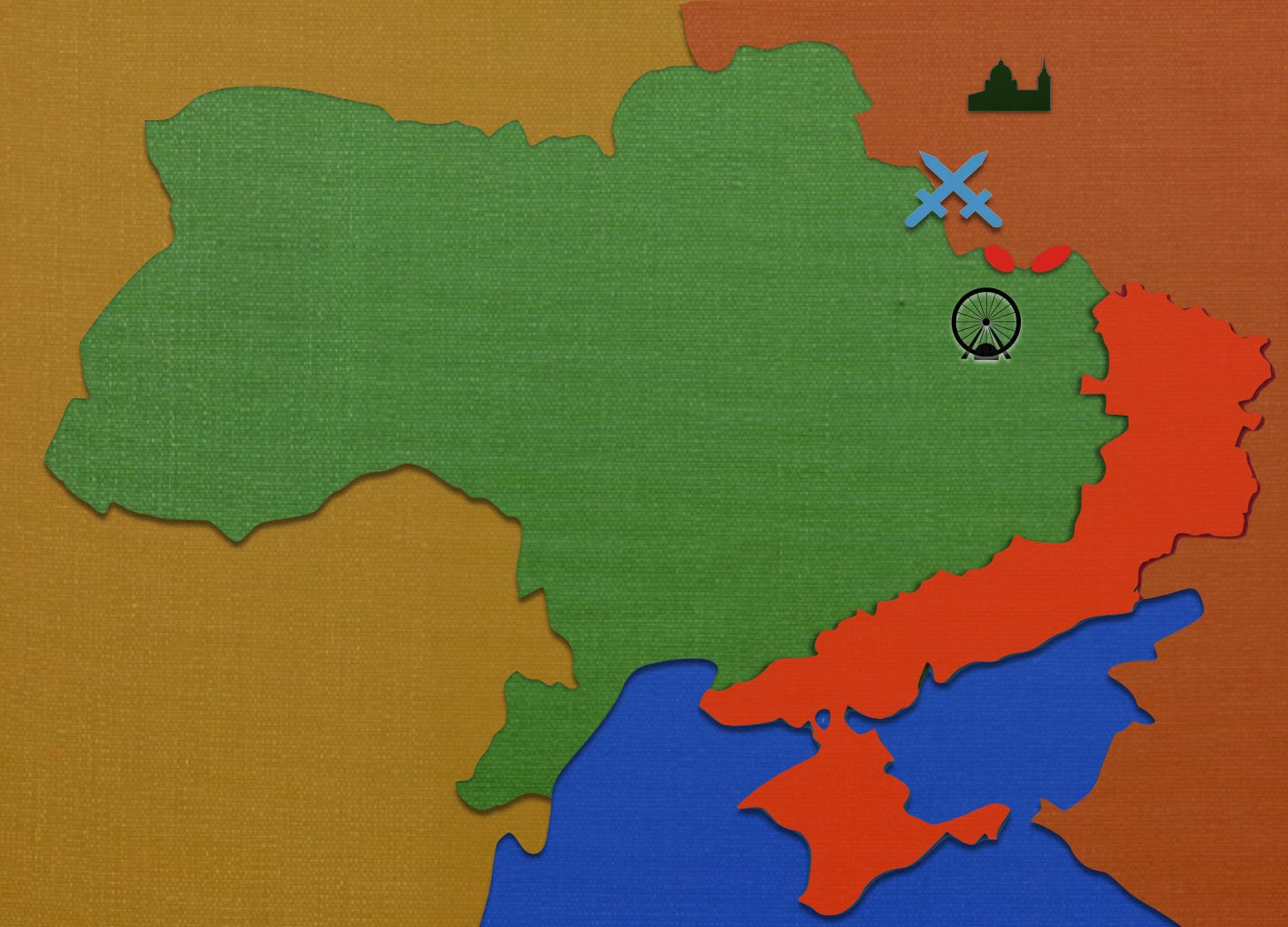

Such has been the case for much of the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine. In many phases in that conflict, substantial portions of the borderlands that connect the territory of the two belligerents saw little in the way of warlike activity of any kind, let alone the operations of substantial ground formations. In particular, the lion’s share of the frontier that separates northern Ukraine from southern Russia - a stretch that measures some 400 kilometers (250 miles) - proved remarkably quiet for much of the war.

One big exception to this general rule occurred when, in May and June of 2024, the Russians conducted a series of ‘attacks with limited objectives’ north of the city of Kharkiv. Advertised as a means of building a ‘buffer zone’, these created a pair of modest enclaves, each of which extended into Ukrainian territory to a depth of 12 kilometers (7 miles) or so. The other deviation from the overall pattern took the form of the Ukrainian attack in the direction of the Russian city of Kursk that began 6 August 2024.

John J. Mearsheimer has argued that, as the incursion towards Kursk lacks an obvious military objective, it must be nothing more than an exercise in public relations. The formations used in the operation, he adds, would do more good for the Ukrainian war effort if they had been used to ‘buttress the forces that are buckling under the Russian steam roller’ in the eastern part of Ukraine.

I would like to offer a somewhat different view, one that, like so much in The Tactical Notebook, owes much to my studies of the First World War. In the middle years of the latter conflict, the leaders of German formations holding ground on the Western Front came to the conclusion that, after a certain point, putting additional men in a given position did little to augment its power of resistance. Rather, it did little more than increase the odds that a given artillery projectile would find a victim.

In the same period, French and British commanders learned that, in operations that depended upon the explosion of many thousands of such shells, the pace of any advance depended upon the speed with which bombardments could be organized. The latter, in turn, relied upon the rapidity with which trains, trucks, and wagons could deliver stocks of ammunition to firing batteries.

If a similar dynamic governs the fighting in eastern Ukraine, then it would make little sense for the Ukrainians to employ their best reserve formations to ‘buttress’ counterparts in the path of the ‘steamroller’. Rather, a wise commander would look for opportunities to employ such forces in places poorly supplied with artillery ammunition, or, better yet, the means to move, quickly and securely, several thousand hundred-pound rounds.

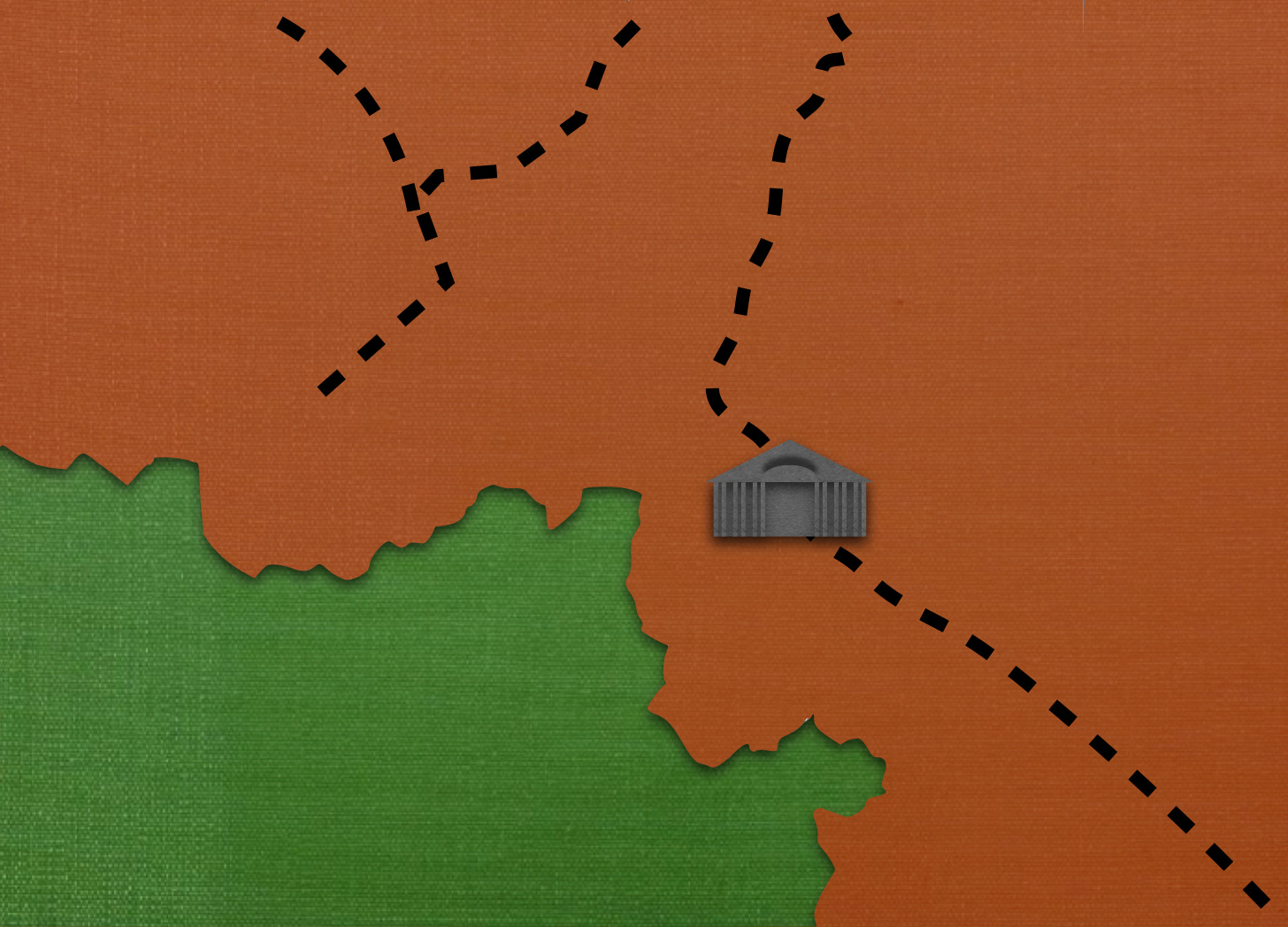

The vast majority of bombardments conducted by Russian forces in Ukraine have occurred in a place well supplied with railroads. Indeed, the rich rail network of the Donbas may well have been the deciding factor in convincing the Russians to fight a long campaign of attrition in that region. The Russian forces fighting southwest of Kursk, however, will have to make do with whatever can be sent along the two lines that run out of that city to the south.

I find that maps are easier to read than the minds of men. I will therefore refrain from speculating about the future course of the Ukrainian incursion into the area southwest of Kursk. That said, it seems that the key to Ukrainian success in this operation is the conduct of a well-ordered withdrawal before the Russians are able to deploy a great deal of well-supplied artillery. After all, if the Ukrainian formations that went into Russia end up on the receiving end of Donbas-style bombardments, they will have deprived an otherwise impressive operation of its raison d’être.

For Further Reading:

To Share, Support, or Subscribe:

“I find that maps are easier to read than the minds of men.” As do most of us 🤣 You sir, have a gift for understatement!

The larger issue is one we cannot know from here - what the actual objective of the operation really is (the end state if you will). As alluded to by others, the Ukrainian armed forces do not have the strategic reserves to continue the Kursk offensive and hold on elsewhere. If this is a raid, they had best get on with this and, as you advise, conduct a retrograde before the Russian God of War intervenes.

Another development: https://www.wsj.com/world/europe/russia-withdraws-some-forces-from-ukraine-in-response-to-kursk-invasion-c0a11eee?st=rd1rj7rs6lpw0g0&reflink=article_copyURL_share