Deployment Plan von Staabs

The Great "What If" of 1914

On 1 August 1914, at five in the afternoon, Kaiser Wilhelm II commanded the mobilization of the armed forces of the German Empire. A few minutes later, a telegram arrived from London.

Sent by Prince Lichnowski, the German Ambassador to the Court of Saint James, the telegram contained a promise from the British foreign secretary, Sir Edward Gray. If Germany refrained from attacking France, Sir Edward had told Lichnowski, Britain would keep France out of the war that had just broken out between Germany and Russia.

For the Kaiser, and most of the senior officers and officials gathered around him, this was excellent news. It meant that, rather than having to fight a two-front war, Germany would be free to devote the lion’s share of its forces against Russia.

One officer, however, thought poorly of this promise. Colonel General Helmuth von Moltke, nephew of the famous field-marshal of the same name and chief of the General Staff, believed that British antipathy towards Germany was so great that the British Empire could not fail to make common cause with France and Russia.

Thus, when the Kaiser exclaimed “now we can simply send the entire army east,” Moltke replied that such a deployment was impossible. “The deployment of an army of a million men,” he argued, “cannot be improvised. It would be the work of a full, exhausting, year and, once completed, could not be changed.”

The Kaiser expressed dismay at this response. “Your uncle,” he told Moltke, “would have given me a different answer.” Nonetheless, he accepted the argument that, for “technical reasons,” there was no alternative to the deployment of nine-tenths of the armed might of the German Empire against France and Belgium.1 Thus began a long series of disasters that, a little more than four years later, would culminate in the collapse of the German Empire.

In the early 1920s, Hermann von Staabs, a retired general officer with much experience in the crafting of deployment plans, wrote a little book that described an alternative to the Schlieffen Plan. After providing a short history of such the evolution of such plans in the four decades that followed the unification of Germany, he contended that, notwithstanding the claims made by Moltke on 1 August 1914, the dispatch of substantial forces to the east could, indeed, have been improvised.2

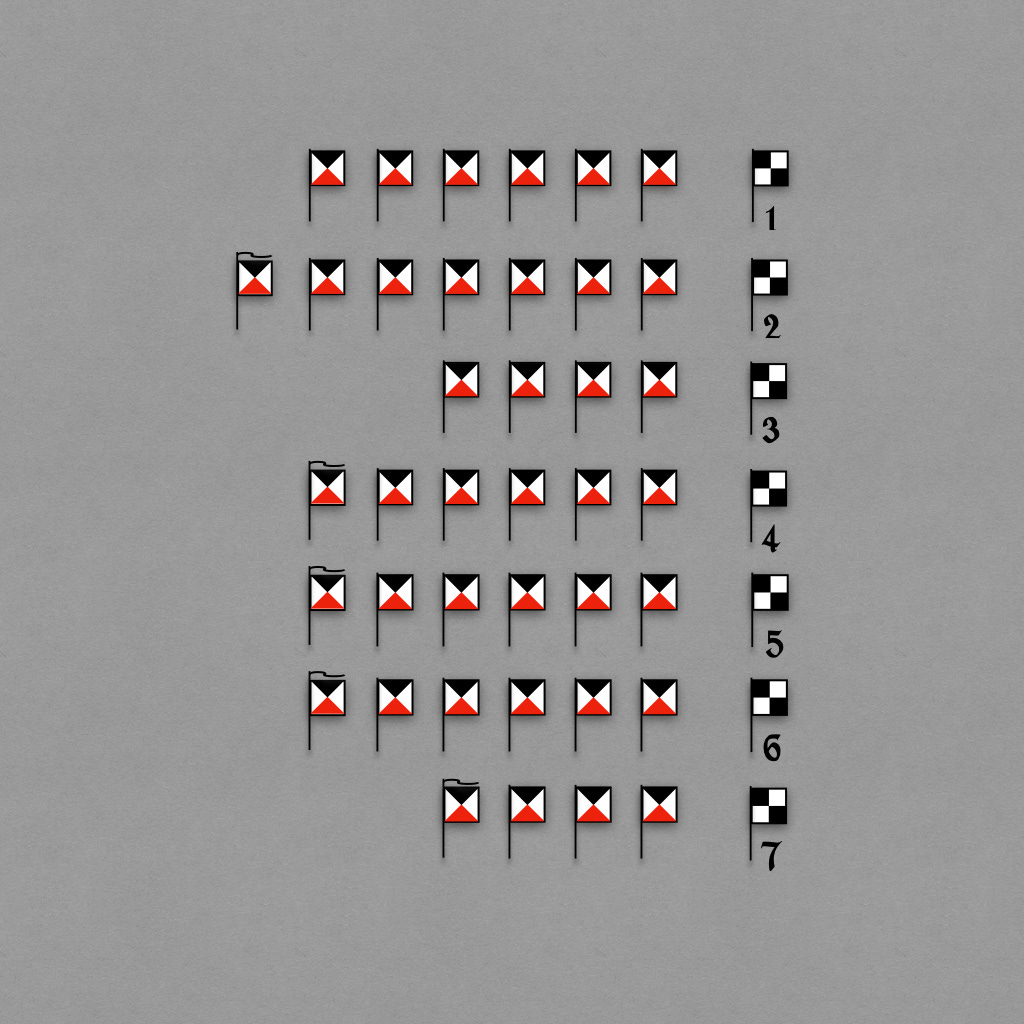

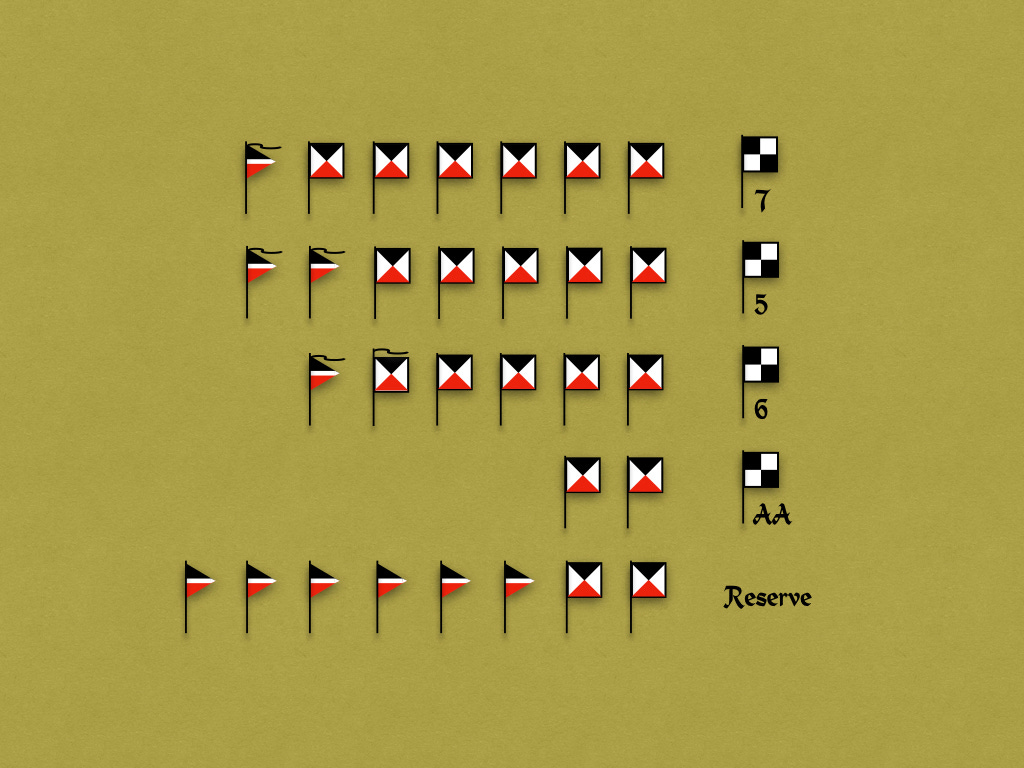

In the course of making his case, Staabs described an imaginary deployment in which twenty-one German army corps marched against Russia while nineteen such formations took up defensive positions on the Franco-German border. (Where the actual deployment of 1914 made use of twenty-five active army corps and fourteen reserve corps, the imaginary deployment described by Staabs employed twenty-five active army corps, fourteen reserve corps, and an improvised corps composed of Landwehr units.)

For Links to the Other Posts in This Series:

To Share, Subscribe, or Support:

Helmuth von Moltke and Eliza von Moltke Erinnerungen, Briefe, Dokumente, 1877-1916 (Stuttgart: Der Kommende Tag, 1922) pages 18-20

Hermann von Staabs Aufmarsch nach zwei Fronten (Berlin : Mittler & Sohn, 1925)

A further extension of this I think is due: Should Germany adopt a defensive posture in the West and France say to hell with it anyway, does Britain stay out after failing to restrain their would-be ally? Does French revanchism decide the violation of Belgium from the West worthwhile to stab at Germany? How does Britain react to that? It really is one of the truly great "what ifs?" of history.

I just recently read on this in the History of the German General Staff. Would be interesting to peer into another world where things went differently.