This post continues the serialization of Battalion Organization, an article, published in 1912, in the Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, that argued for the replacement of the traditional eight-company battalion with a unit made up of four much larger companies. A copy of the original article can be found here, at the Military Learning Library.

The first post in this series can be found by means of the following link:

The Battalion in War

Gentlemen, we have a new situation to face in Europe, one which did not exist when our army was distributed in its foreign garrisons and made up to war strength in them. The navy as you know has recently scrapped obsolete ships and concentrated in home waters. May I suggest that perhaps the army may have to scrap some of its cherished ideas in order to face the situation in its turn? And will you permit me to say that we have now to look nearer home than the Afghan frontier, or even the Mediterranean Sea?

If we are ever to fight a great battle in Europe, we stake our fortunes upon the Expeditionary Force, and the tactical handling of the infantry of that force will be a deciding factor as far as our army is concerned. Whether we fight alone or at the side of, and in close co-operation with, a European army, or whether we undertake a separate mission, as the ally of a friendly power, it is obvious that our Expeditionary Force must be ready to take on twice or three times its own numbers on the field of battle. We did it often enough in the old days of amateur armies, raised for each war and usually disbanded at its termination, and I am convinced we can face similar odds under modern conditions, if we evolve a system of fire tactics suitable to the characteristics of our people and devise an organization calculated to develop those fire tactics. At the present moment I submit that our battalion organization is many years behind our fire tactics, that the latter are as good as or better than any in Europe, but that we are failing to develop them along progressive lines, because we arc hampered and thrown back by an eight company system, which destroys the initiative of subordinates without increasing the legitimate control of superior commanders.

A battalion is, therefore, more or less in a difficulty every time it deploys for attack, and the keynote of our tactics “no movement without fire” suffers from an unconscious conflict between theory and practice. The eight company battalion was very convenient when we fought in lines of two or more closed ranks, and the commanding officer and captains could be heard by everyman in those ranks. But, it is unsuitable to the wide and deep formations which modern weapons compel a battalion to assume in an attack, and it is positively detrimental to co-operative fire tactics, which are based upon the initiative of in individuals in the firing line backed by the supporting fire of their comrades behind. In other words the sections advance from fire position to fire position, in the confident belief that a plan has been pre-arranged for the covering fire of all neighboring companies. With four or more companies in the firing line this pre-arrangement is extremely difficult and is usually neglected, because there is no time or place for four or more captains to consult one another before they act.

Let me give an illustration of what I mean:

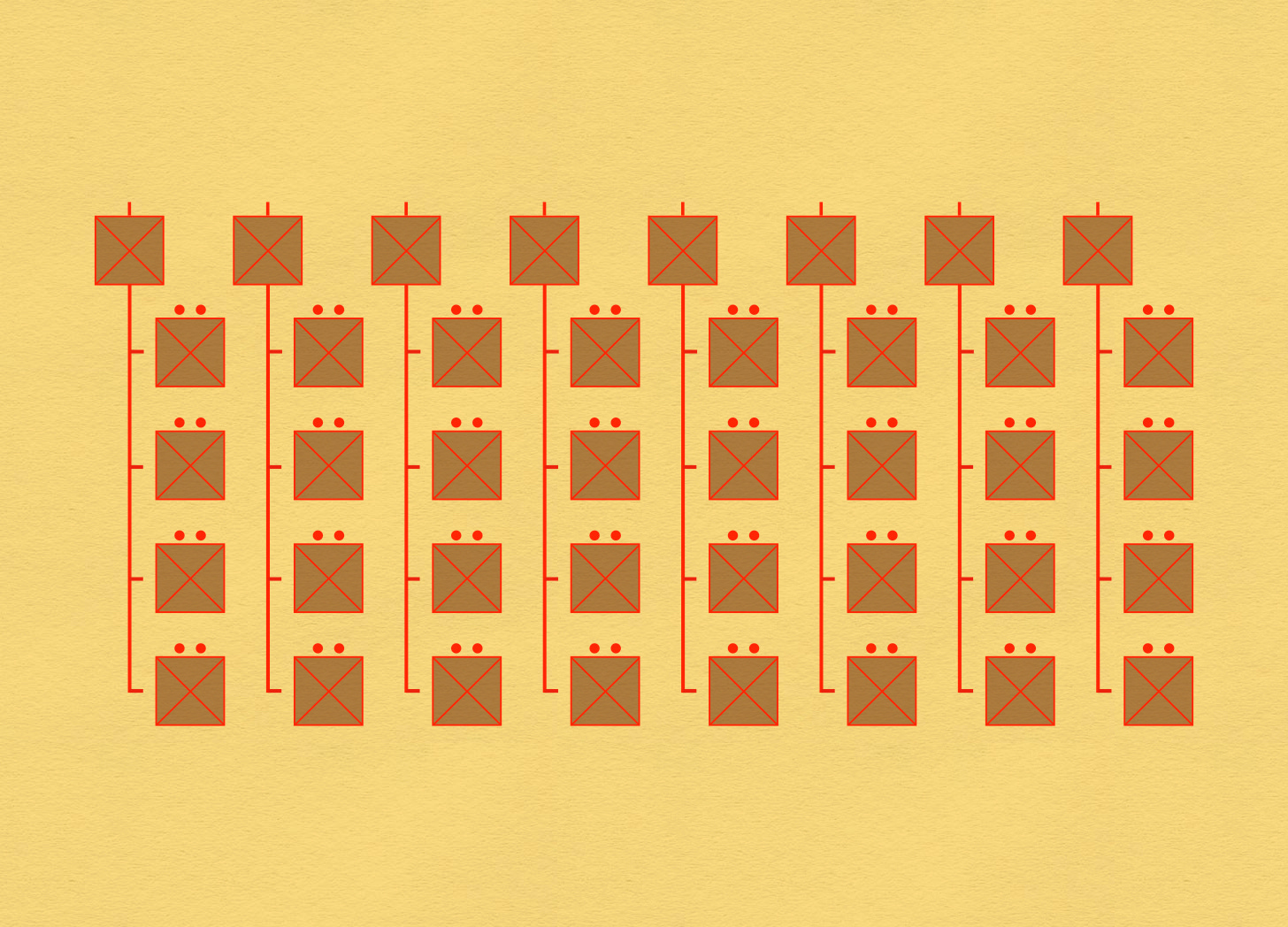

An eight-company battalion, just mobilized to war strength, is about to be launched in its first attack upon the enemy in a European battle. The commanding officer has been shown his objective, less than a mile to his front, and has been detailed by the brigadier to push home the attack in conjunction with another battalion of the same brigade, and in co-operation with another brigade on the flank. He has assembled his company officers, explained his orders and intentions, and has told off four companies as firing line and support, two companies in second line, and two in reserve. He accompanies the reserve.

The senior major is put in charge of the four leading companies, and this is where the first difficulty arises. How is the senior major to exercise any useful or desirable control over four independent companies, hotly engaged with the enemy and spread out along a frontage of nearly half a mile? He has no staff and no horse, so he probably attaches himself to one of the center companies and either interferes too much with its captain or does nothing at all. On arriving in the first fire position he may be able to arrange for the further advance, but it is more than likely that he will never get into touch with the outer companies on the flanks of his firing line. My point is that he senior major is, under the circumstances, a good man wasted, because he has been given an impossible task.

If, however, there were two big companies in the firing line instead of four little ones, the senior major’s job would be to coordinate the general advance, and without interfering in details, arrange with the two company commanders for mutual assistance in the difficult operation of moving forward, under the enemy’s bullets, from fire position to fire position. The attack would acquire an intensity which it at present lacks. In fact our infantry could strike much harder blows.

We will next turn our attention to, and follow the fortunes of, one of the four captains in this first battle, and see how he too is handicapped by our present organization and its unmethodical chain of responsibility. This captain, probably for the first time in his life, has two subalterns under his command in action, with one of whom he has an acquaintance of only a few days. His four sections are commanded by four sergeants, two or three of whom were only promoted a few days before, namely, on mobilization. Of the rifles actually in the ranks some 60 per cent are newly joined reservists, and a small proportion are recruits who have never done a company training. The reservists were all discharged from the battalion in India, and may never have seen their section commander or officers before. They are a splendid body of seasoned men, a little rusty in fire discipline, but capable of magnificent soldier-work under trained leadership. Nothing should, therefore, be omitted which can possibly foster and develop the training of the leaders.

Now, the first problem confronting our captain is how to arrange the duties of his two subalterns to the best advantage. Each subaltern is supposed to command a half-company of two sections, but for excellent reasons the two sections are not, and cannot be, permanently the same two sections, partly because a half-company is not a tactical unit and seems only to have been invented to give a nominal command to a subaltern, and partly because the four sections of a company take certain duties in turn and do not work in fixed pairs. In fact, infantry subalterns have no definite command, no real responsibility, no permanent job, as they have in the cavalry and the artillery; and this is one of the worst features of the eight company system.

The result is that our friend the captain has to improvise at a critical moment the roles of his lieutenants; and he probably sends forward his trained subaltern with the firing line and keeps his untried subaltern with the supports under his own eye. It is the best he can do, but is nevertheless a makeshift arrangement which is avoided in a four-company battalion, as will be shown hereafter. We can therefore leave our battalion to prosecute its attack. We hope for a successful issue to the event, but I, for one, am convinced that its success will be gained in spite of an organization which handicaps it throughout.

For the fact remains and stares us in the face whenever we look closely into the question—that the controlled action of eight independent companies in the stress of battle is a hopeless undertaking for any individual. If he holds them tight, he destroys initiative. If he lets them go, they lose cohesion. The solution seems to be to delegate increased powers to fewer responsible officers in command of enlarged companies. Eight units are too many for co-operative fire tactics, which necessitate a study of ground and an intelligent use of it. To arrange for covering fire, to obtain the support of artillery and machine guns, to co-operate with neighboring units, and yet to maintain the fire fight with the enemy, all these desirable objects are rendered more difficult of attainment by eight companies than by a lesser number.

The next post in this series is:

To share, subscribe, or support:

This is a stunning series (so far). I can’t help but think of Andrew Lambert’s THE BRITISH WAY OF WAR. He argues against a larger army in favor of a navalist approach (which I sympathize with). However: this presents an interesting counter balance, which is relevant today. The author mentions a scale that the Army would have to face in a future combat, coinciding with a need for greater professionalism and training brought about by modern weaponry. Sounds familiar.

Great read as the British army attempts to modify tactics based on the advances in technology.

Today’s infantry battalions continue to modernize and tweek organization to adjust and adapt to the changing battlefield.

https://www.marinecorpstimes.com/news/your-marine-corps/2023/09/08/the-new-marine-infantry-battalion-is-slimmer-saltier-and-more-techy/