The story of the 1st Battalion of the 121st Heavy Artillery Regiment [1ère Groupe du 121e Régiment d’Artillerie Lourde] begins in February of 1915. In that month, officers, non-commissioned officers, gunners, and drivers who had learned the artillerist’s art in other regiments came together to form one of the first units of the French Army to be equipped with the Model 1913 105mm guns that had begun, ever so slowly, emerge from the Schneider works.

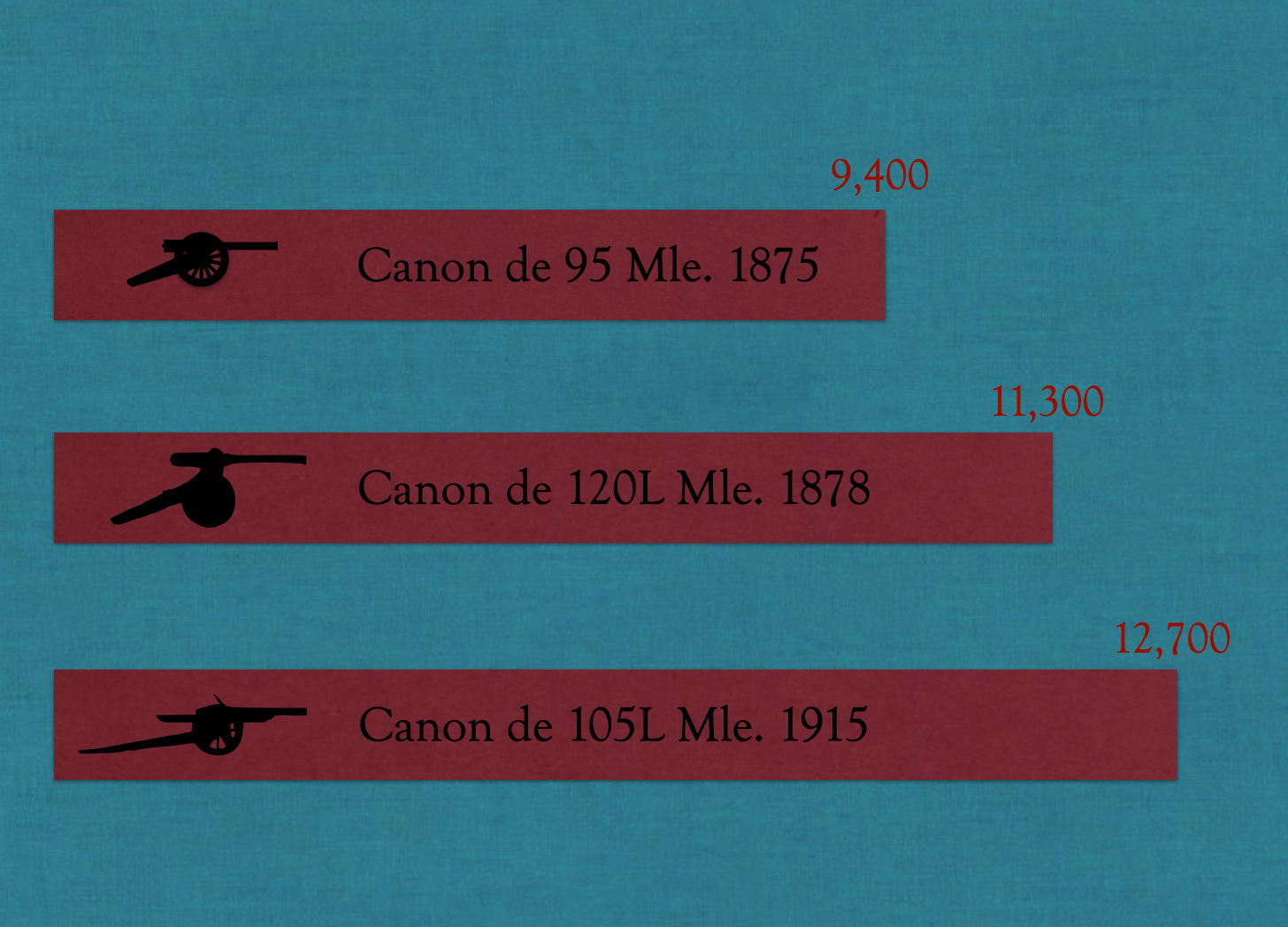

In terms of range, weight, and weight of shell fired, the new weapon resembled the 120mm piece (Model 1878) it had been acquired to replace, both in the defensive arsenals of French fortresses and the batteries of mobile heavy artillery regiment. In terms of rate of fire, however, it surpassed its predecessor by a factor of seven. (That is, while the 120mm gun could fire one round in a minute, the new 105mm piece could dispatch seven rounds in the same period of time.)

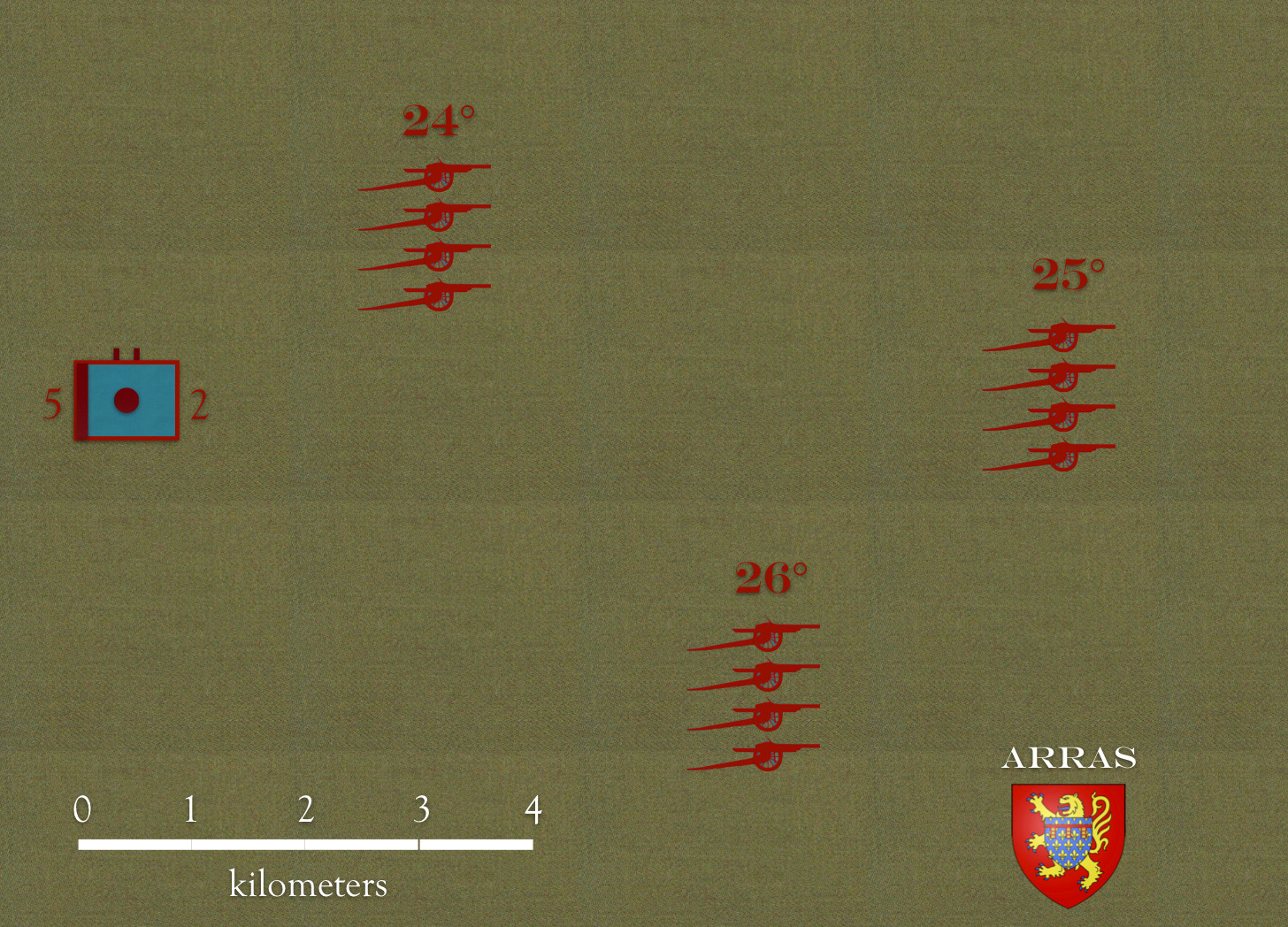

The new battalion came together at Vincennes, just east of the city limits of Paris, in the barracks that, on the eve of the outbreak of war, had hosted the 2nd Heavy Artillery Regiment. Indeed, though it never served alongside other elements of that unit, the battalion bore, for the first eight months of its existence, the title of the 5th Battalion of the 2nd Heavy Artillery Regiment [5e Groupe du 2e Régiment d’Artillerie Lourde]. (In keeping with this designation, the three component batteries of the battalion, the 24th, 25th, and 26th batteries, received numbers that reflected their seniority within the regiment.)1

On the afternoon of 31 March 1915, the battalion took up positions east of Verdun, at the foot of the ridge that separated that soon-to-be-famous fortress from the German-held plain to the east. There, in keeping with the French policy of reserving 105mm pieces for tasks particularly well-suited to quick-firing weapons, it often found itself waiting it readiness to deliver brief, but intense, concentrations of shells upon German batteries that revealed themselves in the course of an engagement.

After spending seventeen days near Verdun, the battalion moved to the suburbs of the city of Arras. There, each of the three four-piece batteries, fed by its own ammunition column, informed by its own observation post, and changing its location in accord with local conditions, operated with what was, for the time, an unusual degree of independence. (This mode of employment seems to have stemmed from the desire of the commanding general of the Tenth Army, to which the battalion was assigned, to “spread the wealth” where quick-firing heavy guns were concerned.)

The battalion operated in this manner during the great Anglo-French attack of May and June of 1915, the larger offensive that began on 9 September 1915, and the short summer of position warfare that connected those two great battles.2 Notwithstanding the ferocity of the fighting that took place at either end of this period, the casualties suffered by the battalion were, by the standards of the First World War, extraordinarily light. Indeed, all four of the men of the 24th Battery evacuated for wounds during this period had been injured when a single shell exploded, prematurely, in the barrel of one of that unit’s guns.3

On 1 November 1915, a general reform of the organization of the heavy artillery of the French armies in the field assigned the 5th Battalion of the 2nd Heavy Artillery Regiment to the 21st Army Corps. In keeping with this new assignment, the battalion became the 1st Battalion, and the batteries the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Batteries, of the heavy artillery establishment [artillerie lourde de corps d’armée] of that formation, the freshly minted 121st Heavy Artillery Regiment.

In January and February of 1916, after nine months of fighting, the 1st Battalion of the 121st Heavy Artillery took a well-earned break from frontline service. While it spent part of this time out of the trenches serving as school troops for a training course, the unit also enjoyed an opportunity to rest, maintain its equipment, and welcome the young officers who took the places of battery commanders and senior lieutenants who had been promoted to positions of greater responsibility.

On 7 March 1916, while people in New Orleans were celebrating mardi gras, the battalion reported for duty at the fortress complex of Verdun. There, for a period of a little more than eleven weeks, it spent its days bombarding, with the aid of airborne spotters, German batteries, and its nights firing on the routes used by ration parties, runners, and reinforcements.

Continual use took a heavy toll of the 105mm guns of the 1st Battalion of the 121st Heavy Artillery. Some wore out. Others were destroyed by German fire. A few fell prey to premature detonations. On 13 April 1916, the unit, which rated twelve guns, had been reduced to eight. Rather than operate three understrength batteries, it divided the weapons of 3rd Battery among its two counterparts. Thus, what had been a battalion of three four-piece batteries became a unit of two four-piece batteries and a labor company.

On 25 June 1916, after a short rest behind the lines, the battalion returned to Verdun, There the two batteries that possessed guns took up positions that allowed them to fire upon Mort-Homme, the fiercely contested heights northwest of the fortress. A month later, it traded its remaining quick-firing heavy guns for a set of smaller, much older, and far less capable pieces: 95mm guns of a model already in service in 1876, the year in which George Armstrong Custer had made his famous last stand.

With these older weapons, the 1st Battalion of the 121st Heavy Artillery took part in the battle of the Somme. As the limited range of the 95mm guns often precluded their use against German batteries, the three batteries often found themselves firing upon the trenches that sheltered German infantrymen.

On 6 October 1916, the battalion took delivery of a dozen 105mm guns of the type that it had used during the first year-and-a-half of its existence. As a result, it was able to return to the sort of work that had characterized its service in Artois and at Verdun. Unfortunately, the Germans had begun to respond to this combination of observed counter-battery fire and unobserved harassment with what American gunners of the Second World War would come to call “time on target” strikes. Thus, there were many occasions when batteries of the 1st Battalion of the 121st Heavy Artillery found themselves on the receiving end of sudden concentrations of shells fired by all German guns and howitzers, whether light or heavy, that happened to be in range.

1917 brought a degree of respite from the costly battles of the previous year. In the winter, the battalion took part in large-scale exercises designed to provide the 21st Army Corps with a chance to practice the arts of mobile warfare. In the spring and summer, it occupied relatively quiet sectors. In the fall, it took part in the most successful French offensive of the year, the great “attack with limited objectives” at La Malmaison. After that triumph, the 21st Army Corps, and thus the 1st Battalion of the 121st Heavy Artillery, spent six additional months in places, whether behind the front or in the Vosges mountains, free of large-scale fighting.

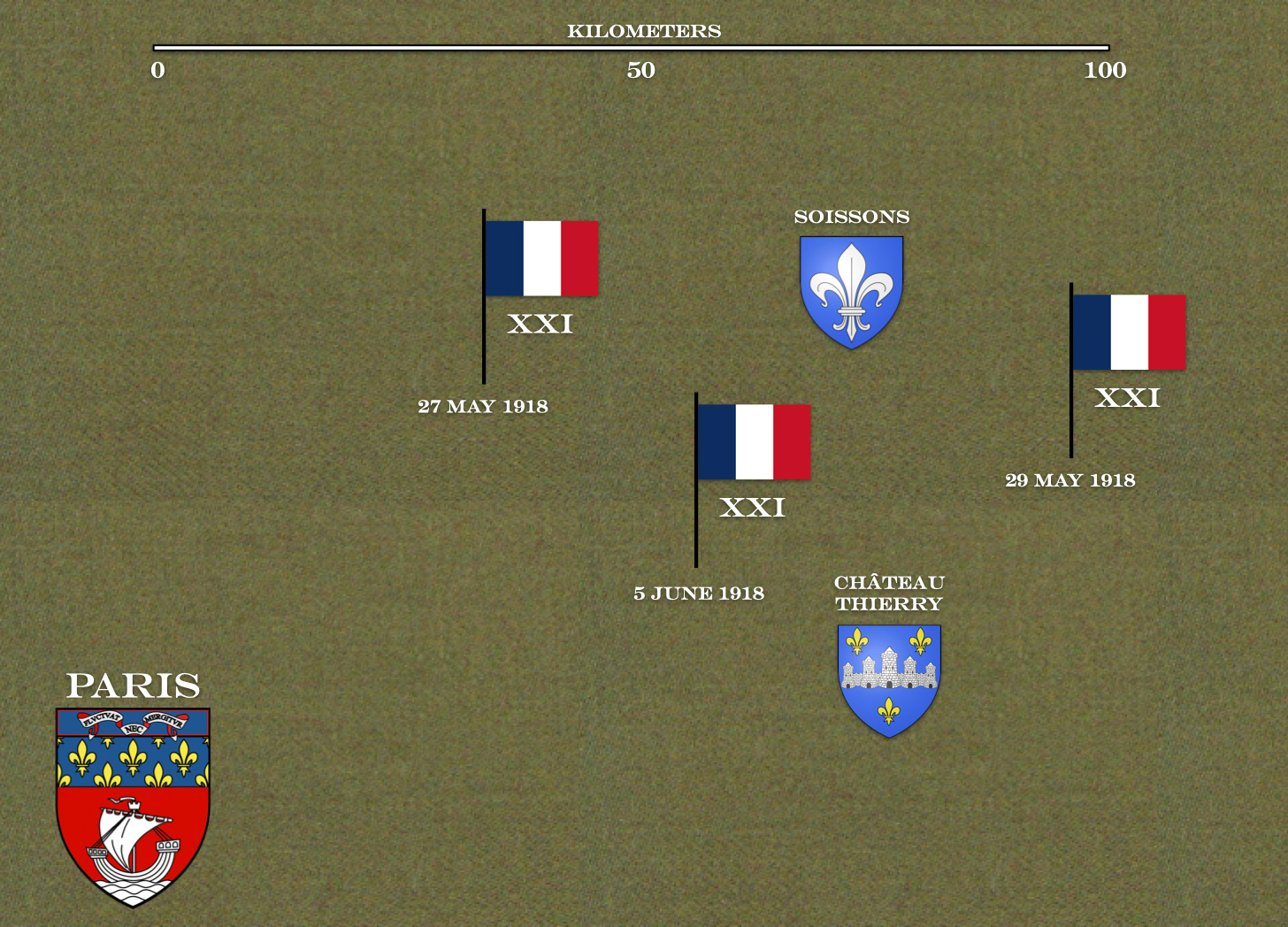

In the third week of May of 1918, in anticipation of a German offensive in the vicinity of Soissons, the 21st Army Corps assembled in an area about forty kilometers southwest of that ancient city. When, on 27 May 1918, the expected offensive materialized, it moved east. Two days later, the 21st Army Corps made contact with the advancing Germans in the valley of the Vesle River, twenty kilometers or so southeast of Soissons.

In the course of this encounter, the danger that German infantry might overrun the position held by the 1st Battery of the battalion was so great that the commanding officer ordered the destruction of its guns. Happily, before the gunners managed to set off the charges, the fully-horsed limbers of the battery arrived. As they hooked up three of the guns and rode away, the crew of the fourth piece kept the Germans at bay with a heavy volume of point-blanc fire.

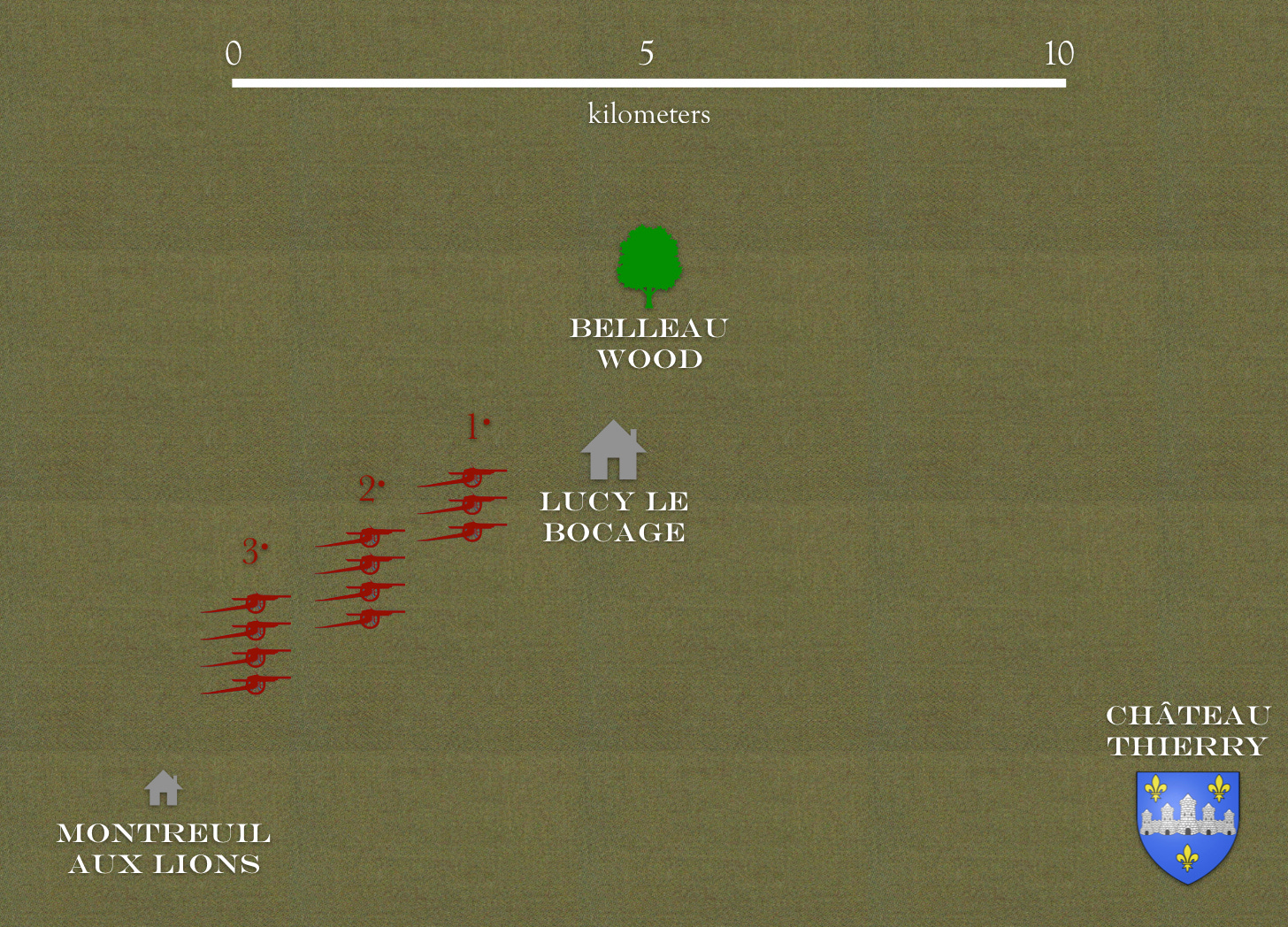

On 1 June 1918, after three days of movement, the 1st Battalion of the 21st Heavy Artillery found itself among the woods, villages, and wheat-fields west of Château-Thierry. There, as the seemingly endless columns of the 2nd Division of the American Expeditionary Forces marched past, it took up battery positions southwest of Belleau Wood. In the four weeks that followed, as American Marines fought in, and around, that soon-to-be-famous forest, the 1st Battalion of the 121st Heavy Artillery spent the long summer days in attempts to silence their German counterparts and the short summer nights complicating movement behind the German lines.

Sources:

War diary [Journal de Marches et Opérations] of the Heavy Artillery of the 21st Army Corps [Artillerie Lourde 21e Corps d’Armée] 18 January 1916-10 November 1919 Archives de Guerre Série 26N, Carton 195, Dossier 11.

Histories of the 121st and 421st Heavy Artillery Regiments [Historiques des 121e et 421e régiments d'artillerie lourde] (1914-1919) (Chaumont: Société nouvelle d'imprimerie champenoise, 1920)

For Further Reading:

The twelve peacetime batteries of the 2e Régiment d’Artillerie Lourde were numbered in a series that began with one [1ère Batterie] and ended with twelve [12e Batterie.] The first three batteries to be formed after the outbreak of the war were numbered in a wartime series that began with twenty-one [21e Batterie].

As Arras is located in the historic region for which the artesian well was named, the fights that took place in the late spring and autumn of 1915 are often called, respectively, the Second and Third Battles of Artois.

In many respects, the 105mm heavy gun might be described as a scaled-up version of the standard French field piece of the day, the famous Model 1897 light field gun. In particular, both pieces used relatively large propelling charges to impart a great deal of speed to the shells that they fired. It is thus not surprising that, while the 105mm gun did not suffer from premature explosions to the same degree as 75mm field guns, it seems to have experienced such accidents more frequently than artillery pieces of other sorts. For the opinion of Joseph Joffre on this matter, see his letter to the minister of war (1er Bureau, No. 4373) dated 11 June 1915, reprinted as Annexe No. 554 to Tome III of Les Armées Françaises dans la Grande Guerre.

This is a great short historical summary. One is amazed at how small the 21 Corps Artillery was and how ill equipped: one lone regiment of only 3 battalions (12 firing batteries) and only 2 (?) with modern weapons. Schneider must have had enormous difficulties producing enough Canon de 105L Modèle 1913 to supply the French Army as it was clearly superior to the older systems. I do wonder why its maximum elevation was limited to +37 degrees if it was intended as a counter battery weapon. Since its maximum range of 12,700 meters could have been extended a good distance of its maximum elevation was +45 degrees instead. Still, it was far better than the +18 degrees of the “Fabulous French 75”, the +16 degrees of the QF 18pdr Gun or the +15 degrees of the 77mm Field Gun M96nA (there is a real price for optimizing your Direct Support artillery for speed and direct fire).