Saints and Strangers tells tales of the early days of the Plymouth colony, an episode, rich in deprivation, danger, and diplomacy, that began with the landing in New England, in the autumn of 1620, of the people we now call ‘Pilgrims’, and ended, in the spring of 1623, with a fight between a squad led by Miles Standish and a group of indigenous Euroskeptics.

The great strength of the film lies in the portrayal of the Algonquin leaders who dealt with the problems posed, and opportunities offered, by the colonists. Whether friend, foe, or frenemy of the Pilgrims, they appear as multi-faceted, fully human people engaged in what, for lack of a better name, might be called ‘armed politics’. Thus, for example, the most prominent of these decision-makers, the Wampanoag monarch Massasoit, must simultaneously manage the ordnance-rich, food-poor people who have landed in the middle of his realm; keep other, more powerful, neighbors at bay; and deal with subordinates who, while proclaiming their loyalty, seem eager to take his place.

Unfortunately, Saints and Strangers fails to devote sufficient time to the ‘pol-mil’ condundra faced by Massasoit and his matchlock-wielding friends. This deficiency owes much to the devotion of precious screen time to such matters as the storm-tossed sea-passage of the Pilgrims and their relationships with each other. Such digressions, however, would not have done as much damage to the Schwerpunkt of the story if the film as a whole had been long enough.1

Obliged to shoe-horning too much action into too little time, the scriptwriters mangled the sequence of events. Thus, for example, they placed in the same scene a pair of incidents that, in actuality, had been separated by a good four months and at least twenty miles. (The first of these was the death, in November of 1622, of Squanto. The second was the first meeting, in February of 1633, over dinner in the home of a leader of the Manomet people, between Miles Standish and a man named Wituwamat.)

In doing this, the scriptwriters saved several precious minutes. At the same time, however, they deprived Captain Standish of a reason for his decision to ambush Wituwamat and his associates. (In real life, the things Standish had heard Wituwamat say over dinner confirmed the information, provided by Massasoit, that Wituwamat was trying to organize an attack against the settlers. In the film, while Standish makes brief mention of his first meeting with Wituwamat, his desire to kill Wituwamat seems to stem from the belief that the latter had poisoned Squanto.)

The makers of Saints and Strangers took similar liberties when it came to weather. The events leading up to the attack, by Standish and his squad, against Wituwamat and his fellow Anglophobes, took place in the depths of a particularly cold winter. Indeed, the presence of snow on the ground and ice on bodies of water played a role in many of the component actions in that great affair. Nonetheless, the cinematic depictions of those occurrences give the impression that they took place on balmy summer days.

Alas, making a version of Saints and Strangers free of the aforementioned deficiencies would have cost a lot more money than could have been recouped by a niche network holiday special. (Packaged as a two-part mini-series, the film made its debut on the National Geographic Channel during the week in 2015 when Americans celebrated Thanksgiving.) With that in mind, it is only fair to evaluate Saints and Strangers for the movie that it is, rather than the docudrama that it might of been.

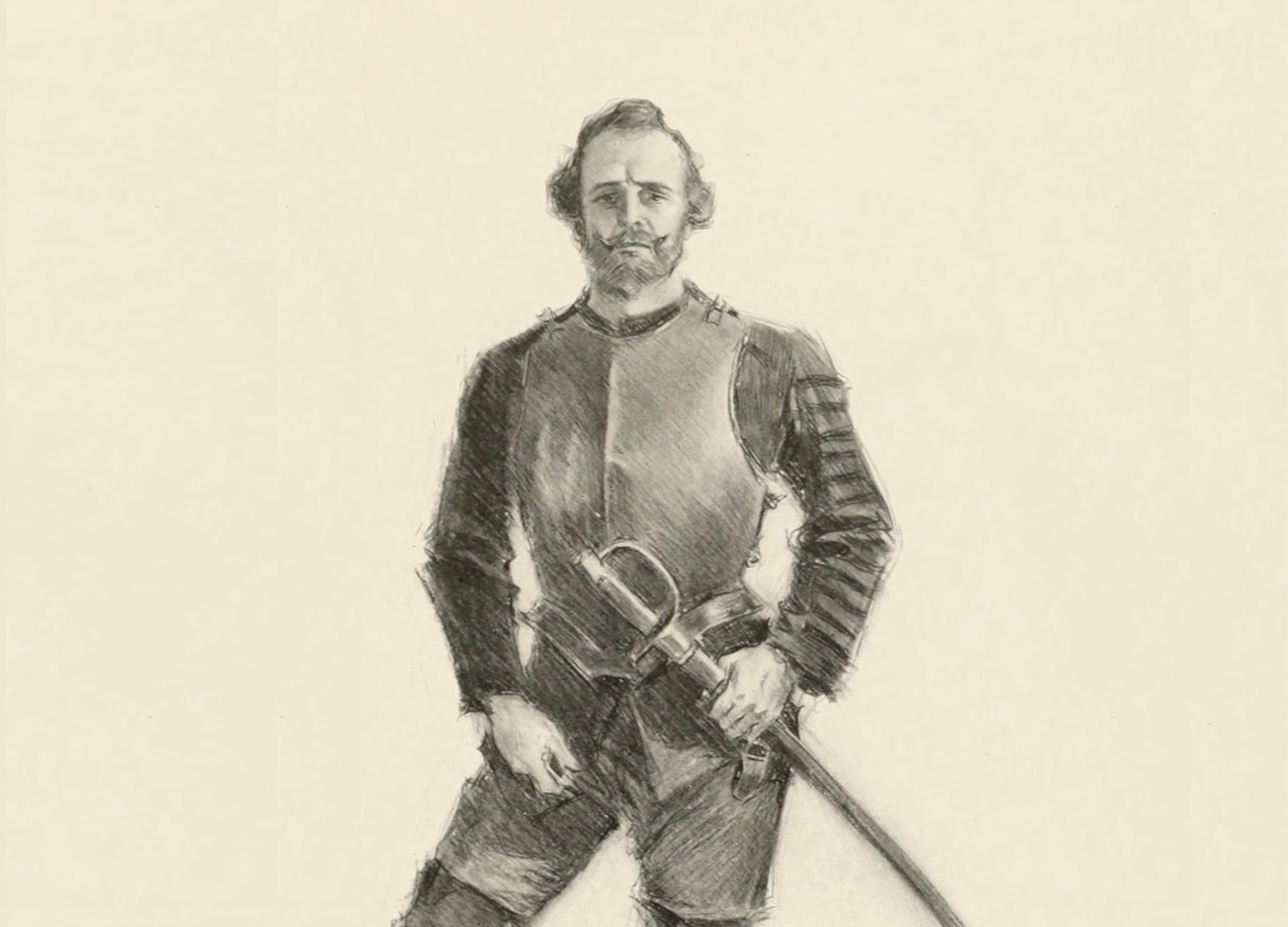

In its current form, Saints and Strangers might do for people contemplating a deep dive into the early history of New England what the Sharpe series does for would be students of the Napoleonic Wars. That is, it will provide services, ranging from mental images of clothing and equipment to ways of pronouncing unfamiliar names, that enable, encourage, and enliven engagement with books, articles, documentaries, and wargames.2

Note: The use of stills from Saints and Strangers accords with the fair use provisions of applicable US copyright law and, in particular, rules related to reviews.

For further reading:

To share, support, or subscribe:

The people who made Saints and Strangers designed it as a two-part television mini-series, with a total running time of 192 minutes.

I have yet to find a simulation that replicates the security challenges faced by the Pilgrims, their allies, or their antagonists in the 1620s. However, readers looking for board wargames set in 17th Century New England will want to look into King Philip’s War and Flintlock and Tomahawk.

There truly is a dearth of stories that deal honestly with how these engagements happened. Which is truly a shame, because if more people understood the actual complicated dynamics at play, maybe we'd stop trying to moralize the history one way or another

(more)

It's not a matter of two opposing narratives - it's a matter of *all* narratives interweaving into where the truth probably actually lies - somewhere in the muddled middle. These things are messy and never ever simple. Because human beings are messy and never ever simple. That is the beauty of this Mystery. The reason the oracle at Delphi admonished the great as well as the small "Know Thyself," is so nobody else would have the ability to decide for you, much less tell you, who they think you ought to be, and also, so you might know everyone else too. We are not that dissimilar from each other where the rubber meets the road.

Ultimately, story telling - the relating of these mythos - is about who has power - and who doesn't. The USSR knew that - so does the CCP. And bending mythos is not just a crime against humanity and culture, it's a weapon of war. Of, "soft power" if you will, that isn't so soft. History is always written by the victors. Sort of. The history of the vanquished, or absorbed, or inconveniently parallelled, is also written but, more obliquely, more, occultly. You have to look harder for it. But like a palimpsest - it's still there.

I'd like to see American Indigenous film production tackle the subject of Miles Standish, the Pilgrims and King Philip. And Native film production is actually a fair sizeable portion of the production ecosystem now. https://variety.com/2021/tv/features/joely-proudfit-inclusion-rutherford-falls-native-americans-indigenous-filmmakers-1234997801/

King Philip's War is a turning point in colonial affairs and one that's not studied nearly enough. "Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip's War" is a fairly recent book on the subject that won the Bancroft Prize in 2019.

Bruce, do you know if there are digital formats of "King Philip's War" and "Flintlock and Tomahawk?"