Recently, while looking for relatively rare pictures of Hans von Seeckt to illustrate my translation of Thoughts of a Soldier, I ran into Hitler over Russia. Bearing the subtitle of The Coming Fight between Socialist and Fascist Armies, this work predicted a German-led invasion of the Soviet Union, the bombardment of German cities by Soviet bombers, and a spontaneous rising of German workers.1

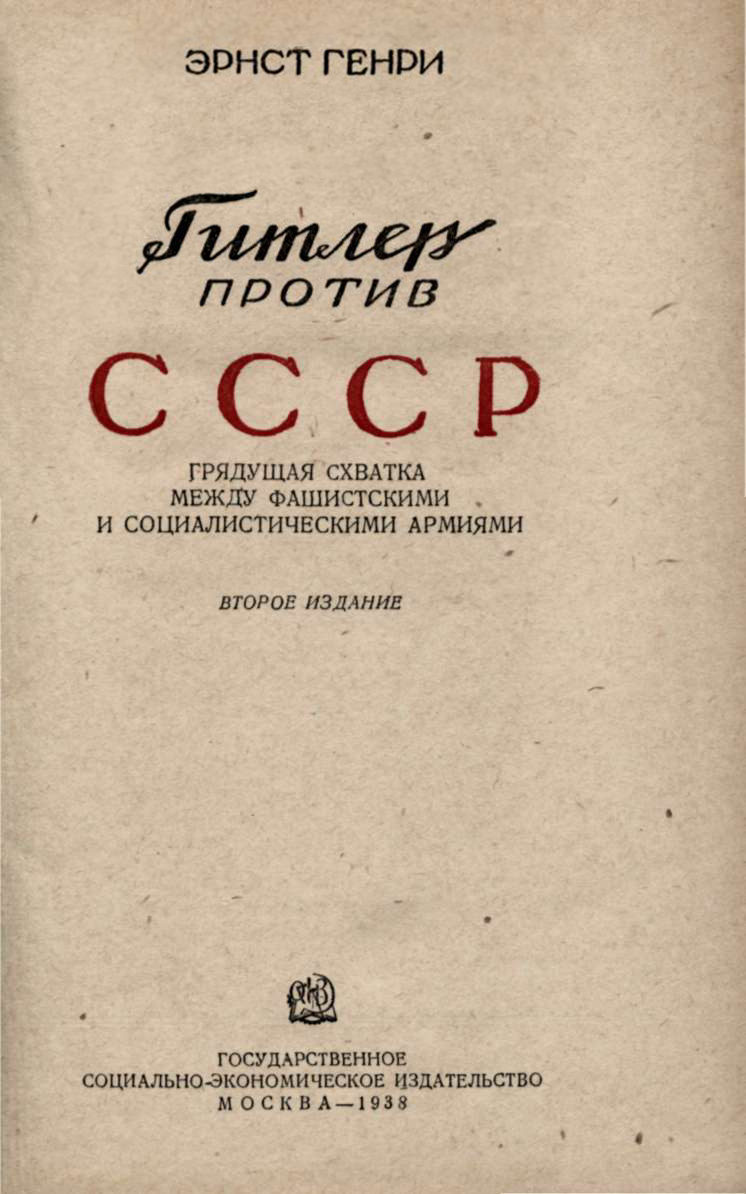

Strange to say, the first copy of this book that I found bore the date of 1936. A search for other copies turned up a British edition (1936), a version written in German (1937) and a translation into Russian (1938).2

The American edition of Hitler over Russia weighs in at 340 pages. Of these, 227 pages - a good two thirds of the total - deal with the internal affairs of Germany and the states located between it and the Soviet Union. Thus, the reader who wishes to focus on the campaign that the author imagines can safely skip the first seven chapters of the work. (That said, I was surprised - and considerably relieved - to discover that, while clearly a believer in the definitive fairy tales of dialectical materialism, the author of Hitler over Russia proved able to discuss both politics and economics without subjecting his readers to quotations from, or paeans to, Marx, Engels, Lenin, or Stalin.)

The War

Once it gets down to fight promised by its subtitle, Hitler over Russia describes a conflict between two alliances. (Germany enjoys the assistance of Finland, Hungary, and, marvelous to say, Poland. The Soviet Union makes do with the help of Czechoslovakia. France and the United Kingdom sit this one out, as does the United States.)

The shooting war begins with two German-led offensives against the Soviet Union, a littoral main effort aimed at Leningrad and an overland attack in the direction of Kiev.

Thanks to German control of the Baltic, the northern attack makes good progress. However, when it reaches Leningrad, the defenders of that city inflict a sharp defeat upon the invaders. (The author credits this great upset to the revolutionary traditions of the Cradle of Bolshevism.)

Lacking the ability to move troops and supplies by sea, the southern attack stalls well before the German, Hungarian, and Polish troops reach the outskirts of ‘the third city of the Soviet Union.’ Offensives on a smaller scale, such as a Polish attack against Czechoslovakia, also fail.

Having stopped the two main thrusts of the attackers, the Soviet ground forces launch a series of counterattacks. While these take place, the air forces of the Soviet Union, equipped with four-engine bombers, make use of the ‘efficient aerodromes’ provided by Czechoslovakia to drop a large number of bombs on German cities.

In keeping with the teachings of Guilio Douhet, the prospect of death from the air convinces German workers to rise up against their oppressors. Thus, under the direction of a ‘fifth column’ of agents of the Comintern, they overthrow the German government. Soon thereafter, German forces in the field split into two camps, the larger of which joins the Soviet armies marching on Berlin.

Evaluation

Hitler over Russia provides few of the sort of military details that gladden the hearts of readers of this newsletter. It does, however, make several deep dives into the peculiars of German and Soviet industry, especially where things like coal, steel, railroads, and petroleum are concerned. Moreover, like other words of ‘futurology’, it reminds us of the limits on our powers of prediction, especially when it comes to war, ‘the realm of uncertainty’.

Source

Ernst Henri Hitler over Russia: The Coming Fight between the Socialist and Fascist Armies (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1936) (Hathi)

The Russian edition of the book, which bore the title of Hitler against the USSR (Гитлер против СССР), advertised itself as a translation of the work of an ‘English journalist’. (Ernst Henry - Our Man in the 20th Century) The American and British editions, however, gave translation credit to Michael Davidson, a Briton who specialized in translating left-leaning works from German into English. (British Library). Published by German exiles living in France, the German-language edition was called Campaign against Moscow (Feldzug gegen Moskau) (National Library of France)

The author of Hitler over Russia sported several appellations over the course of his life. Born in Vitebsk, in 1904, as Leib Abramovich Khentov, he soon adopted the Russified version of that name, Leonid Arkadyevich Khentov. In 1922, while working as an agent of the Communist International (Comintern) and living (for the most part) in Germany, he carried a Soviet passport that identified him as ‘Semyon Nikolaevich Rostovsky’. In 1933, when he moved to England, Comrade Rostovsky divided his time between efforts to recruit agents for Soviet intelligence and the writing of articles for the predecessor of The New Statesman. (For the latter enterprise, Rostovsky adopted the noms de plume of ‘Ernst Henri’ and ‘Ernst Henry’.) (Ernst Henry - Our Man in the 20th Century)

The coal, Iron, industrial insights are undoubtedly informative. The other insights may be contemporary and desired diplomacy.

Poland DID have a non aggression pact with Hitler that lapsed in favor of France, England.

Stalin at that time did offer to defend Czechoslovakia.

There were missed chances for smaller wars that didn’t prevent an enormous war.

Those are some pretty wild predictions and artwork on that poster.