From time to time, The Tactical Notebook will revise, refresh, and republish an article from its back catalogue. This post, which originally appeared during our first month of publication, is one such piece.

In keeping with Rudyard Kipling’s oft-quoted dictum that “The backbone of the Army is the non-commissioned man,” The Tactical Notebook begins this series on the German armies of 1914-1918 begins with a description of the corporals and sergeants who served the Kaiser on the eve of the First World War. Subsequent articles will deal with such subjects as officers, organization, training methods, professional education, mobilization, tactics, and equipment, as well as the reason for the military forces of the German Empire as “the German armies” rather than “the German Army.”

The highest non-commissioned rank in the German armies of 1914 was that of Feldwebel. Corresponding closely to an American “first sergeant” and a British “company sergeant major,” a Feldwebel supervised the interior economy of his company. That is, he was responsible to the commanding officer of his company for all things related to the discipline, appearance, well-being, and morale of that unit. (There was no appointment in the Kaiser’s armies comparable to that of the battalion sergeants major found throughout the English-speaking world, let alone any position comparable to that of a “senior enlisted advisor” to an officer commanding a larger unit or formation.)

One traditional nickname of the Feldwebel was der Spieß. This appellation, meaning “the spike” or “the spear,” paid homage to the 18th-century custom of arming the senior NCO of an infantry company with a spontoon. (Not only did this pole-arm serve as a badge of rank, but also provided a means of dispatching men who tried to run away in battle.) The Feldwebel also bore the moniker of “company mother,” a title that reminded all concerned of the domestic quality of his responsibilities. (The “company father” was, of course, the commanding officer.)

A Feldwebel could be found in every infantry company of the German armies, as well as in each company of Jäger (light infantry) or Pioniere (combat engineers), as well as each battery of Fußartillerie (fortress artillery.) In units of company size that were provided with more than a handful of horses, such as field artillery batteries, cavalry squadrons, and train companies, the highest-ranking NCO bore the title of Wachtmeister (“master of the watch).”

In companies where the senior NCO bore the title of Feldwebel, the penultimate NCO rank was that of Vizefeldwebel. Likewise, in squadrons, batteries, and companies where the senior NCO was known as the Wachtmeister, the next rung on the non-commissioned ladder was occupied by the Vizewachtmeister. (To avoid tiresome repetition and awkward turns-of-phrase, the term Feldwebel will henceforth be used as a generic designation for both Feldwebeln and Wachtmeister. Similarly, Vizefeldwebel will encompass both the Vizefeldwebeln of pedestrian companies and the Vizewachtmeister of well-horsed units of company size. Finally, the term “company” should be understood to indicate any unit customarily commanded by a captain.)

Often translated as “vice sergeant major,” the title of Vizefeldwebel was initially reserved for the one man in each company who served as the right-hand man of the senior NCO. However, in the decade or so leading up to the outbreak of the First World War, men other than the principal deputy of the Feldwebel also held the rank of Vizefeldwebel. Indeed, in 1913 and 1914, it was not unusual for an infantry company to have four or five Vizefeldwebeln present for duty, as well as two or three more, who, while employed outside the company, remained on its rolls.1

Some of the additional Vizefeldwebeln, which were formally designated as “supplementary” (überetatsmässige), filled positions that would otherwise occupied by lieutenants. In infantry, Jäger, bicycle, and machine-gun companies, where lieutenants were in particularly short supply, these “substitute officers” (Offizierstellvertreter) commanded more than a quarter of all platoons. (In 1913, infantry regiments and Jäger battalions were authorized 2,123 supernumerary Vizefeldwebeln. In the same year, those units fielded 8,835 platoons.)2

Other Vizefeldwebeln obtained that rank by virtue of time in service. Beginning in 1906, the officer commanding each company, squadron, or battery had the right to promote one of his Sergeanten to the rank of Vizefeldwebel, provided the latter had served “with the colors” for at least nine years. In sharp contrast to the aforementioned supplementary Vizefeldwebeln, a man promoted in this way continued to perform duties customarily carried out by NCOs. Thus, he might teach rifle marksmanship, manage the supply of consumables (such as bread and candles) issued to a unit, or supervise the small team of tailors and cobblers, and armorers that maintained the uniforms, boots, and equipment of the company. (NCOs who fulfilled these functions were known as Funktionsunteroffiziere.)3

In April of 1914, on the very eve of the outbreak of war, the Prussian War Ministry authorized the creation of Vizefeldwebeln of a fourth type. These, who were also classified as “supernumerary,” filled the places vacated by NCOs who, shortly before retirement, were serving probationary internships with the branches of the civil government in which they wished to make their second careers. (Retired NCOs, who returned to civilian life well before the onset of middle age, did not normally receive pensions. Instead, some obtained grants that allowed them to set themselves up in a small business, while others received preferential access to jobs in such agencies as the post office, the customs service, and the railroad administration.)

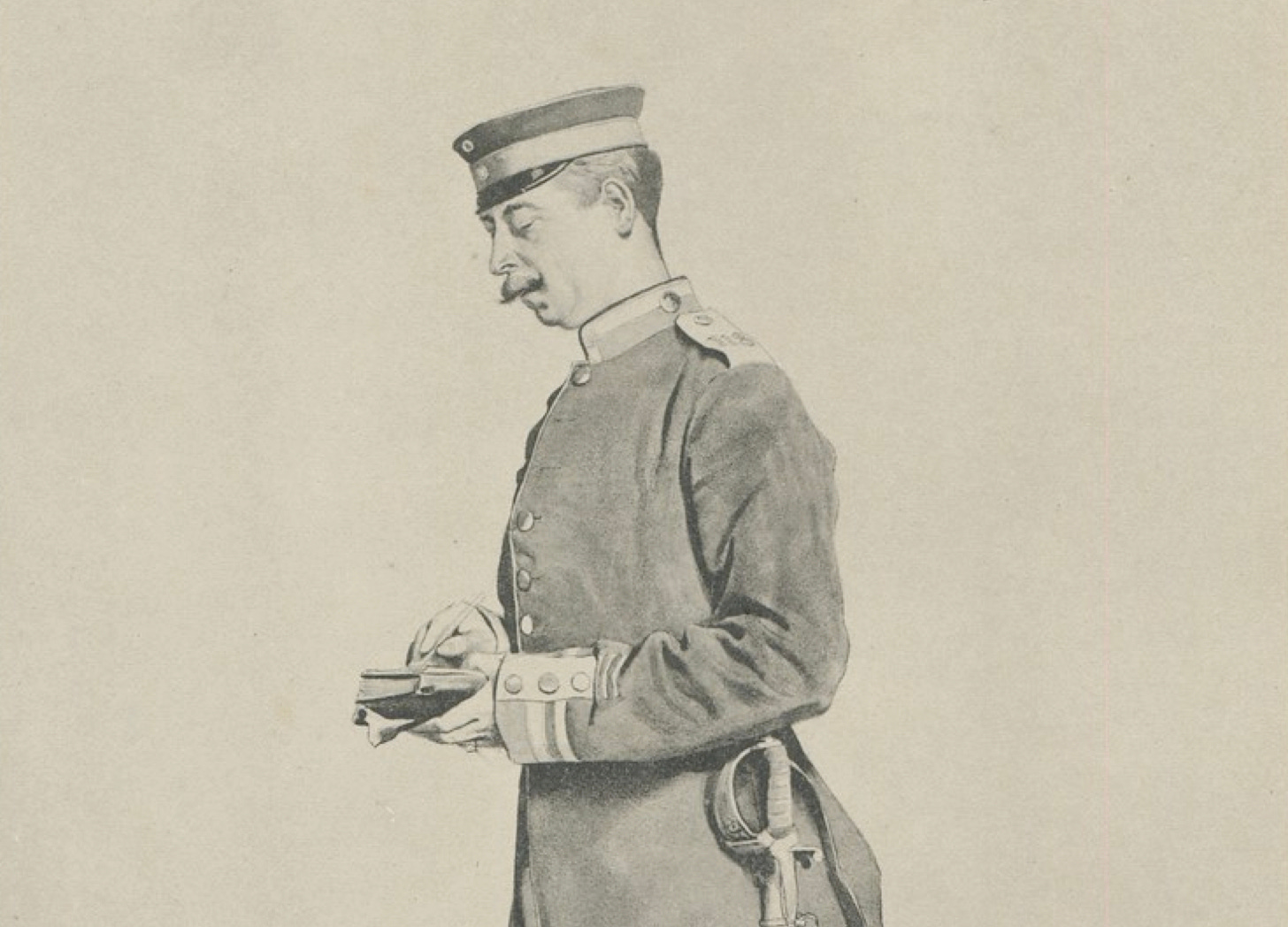

Vizefeldwebeln and Feldwebeln wore sword knots (Portepées) similar to those worn by commissioned officers. For this reason they were often referred to as Portepee Unteroffiziere (“sword-knot NCOs”) or Unteroffiziere mit Portepée (“NCOs with sword-knots.”) NCOs of lower ranks - those of Sergeant and Unteroffizier - wore the enlisted pattern bayonet tassel (or its equivalent for men armed with swords and pistols) and were thus referred to as Unteroffiziere ohne Portepée (“NCOs without sword knots.”)

The appointment of men to the ranks of Vizefeldwebel and Feldwebel was left to the discretion of the officers commanding companies, squadrons, and batteries. The attainment of the rank of Sergeant, however, was largely a matter of seniority. Thus, barring the active opposition of his commanding officer, an Unteroffizier could expect promotion to the rank of Sergeant upon the completion of five and a half years of active service.

While a Sergeant outranked an Unteroffizier, NCOs of both ranks could be found performing the same sorts of duties. Thus a Sergeant or Unteroffizier might serve as a Funktionsunteroffizier, assist a Funktionsunteroffizier, or be given charge of a small administrative unit.

Known as a Korporalschaft (“corporalship”) in infantry units, a Geschütz (“gun”) in field artillery batteries, or a Beritt (“ride”) in the cavalry, a section of this type might be home to as few as eight men or as many as sixteen.

As much of the instruction of new recruits often took place within a Korporalschaft (or its equivalent), and much of this instruction took the form of close-order drill, the leaders of such units devoted much attention to that subject. To put things another way, there was no special class of drill instructors in the armies of the German Empire.4

In the absence of a suitable Unteroffizier, the task of leading a Korporalschaft would be given to a Gefreiter (“freed man”). Though this rank is sometimes translated as “corporal,” the man holding it did not rank as an NCO. Rather, he was a private soldier who, having demonstrated both ability and devotion to duty, had been “freed” (gefreit) from some of mundane obligations and minor restrictions imposed upon most other men in the ranks.

A substantial minority of the Unteroffiziere of the German armies had graduated from one of the nine “NCO schools” (Unteroffizierschulen) of the German Empire. These institutions offered a three-year course of instruction, composed largely of military subjects, for young men between the ages of 17 and 20. (The best graduates of these schools were immediately promoted to the rank of Unteroffizier. The worst graduates joined their regiments as private soldiers. Those who fell between those two categories were appointed as Gefreiten.)

At seven of the nine NCO schools, all students were graduates of NCO preparatory schools (Unteroffiziervorschulen.) These offered a two-year course, composed largely of general subjects, for lads between the ages of 15 and 17. Two of the NCO schools, however, were open to young men who came in directly from civilian life.5

There was no charge for attendance at these schools. However, graduates of NCO schools were obliged to serve for four years “with the colors” while those who had attended NCO preparatory schools acquired a two-year service obligation for each year of studies. Thus, a young man who attended an NCO preparatory school for two years and an NCO school for three years was obliged to serve on active duty for a total of eight years.

The majority of peacetime Unteroffiziere, however, came up through the ranks. That is, having completed two or three years as conscripts, and one or more one-year voluntary enlistments (whether as ordinary soldiers or Gefreiten), they had been promoted to the rank of Unteroffizier by their company, squadron, or battery commanders.

To Share, Subscribe, or Support:

For a detailed case study of the employment of NCOs in an infantry company in 1913, see Laeger ‘Die Unteroffizierfrage’ Jahrbücher fur die deutsche Armee und Marine, Januar bis Juni 1914, pages 589-98.

The figures for supernumerary Vizefeldwebeln and the number of platoons are derived from numbers provided in Löbells Jahresberichte for 1913, pages 4 and 17.

For (somewhat nostalgic) descriptions of the tasks performed by various NCOs in the peacetime armies of the German empire, see Hans-Caspar von Zöbeltitz and Peter Purzelbaum Das Alte Heer: Erinnerungen an die Dienstzeit bei allen Waffen (Berlin: Heinrich Beenken, 1932) pages 100-122.

For an argument in favor of the conduct of recruit training within Korporalschaften (or its equivalents), and against the use of several NCOs to train a larger group of recruits, see Anonymous ‘Rekrutenausbildung durch die Gruppenführer oder durch wechselndes Ausbildungspersonal? Ein Beitrag zur Unteroffizierfrage’ Jahrbücher für die deutsche Armee und Marine Number 468 (September 1910) pages 224-229.

Karl v. Rabenau Die deutsche Land- und Seemacht und die Berufspflichten des Offiziers (Berlin: E.S. Mittler und Sohn, 1912) page 41

I'd never heard of a sword knot (not surprising). I've found images of them on swords, and apart from swords, and officers wearing them with swords, but I still can't figure out how they work. Somehow, they keep the sword from slipping out of your hand. Are there any diagrams or videos that show this?

Interesting to note here the similarities and differences between the German army and the ones they opposed in the World Wars.